The Battle of the Experts: Did the FTC Win the Battle But Lose the War?

As the FTC's trial to break up Meta wrapped, Meta made its last stand with expert economist Dennis Carlton. The FTC rebutted by recalling Scott Hemphill. Who came out on top? And will the FTC prevail?

“And hard by Temple Bar, in Lincoln’s Inn Hall, at the very heart of the fog, sits the Lord High Chancellor in his High Court of Chancery.”

-Charles Dickens, Bleak House

Long before he became the Chief Judge of the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia overseeing the FTC v. Meta Platforms antitrust trial, Jeb Boasberg went to Yale. He played college basketball there, a forward. After earning a degree from Oxford, he returned to New Haven to attend Yale Law, where he lived with future Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh at 61 Lake Place, across the street from the Payne Whitney Gymnasium, home of the basketball team. In the spring of 1989, as a 2L (what we lawyers call a second-year law student), the young Boasberg led a seminar for Yale undergrads, “Law and Literature,” where, in his words, the students “read novels and discussed their depictions of lawyers and courts.” Although his 2010 judicial questionnaire explains that no syllabus from that course remains, it also lists the publication that year in a University of Hartford literary journal of his article exploring those themes from the Charles Dickens novel, Bleak House. The article is worth examining for what he says there about the role of judges.

Bleak House uses the fictitious probate case, Jarndyce v. Jarndyce, to satirize lawyers and their endless pettifogging over technicalities. “This scarecrow of a suit has, over the course of time, become so complicated, that no man alive knows what it means,” Dickens writes. The case finally concludes near the novel’s end with the realization that all the value of the estate has been consumed in legal costs.1

In this parable, the young Boasberg saw Dickens portray “courts entangled in procedural webs,” with “little solace for ameliorating poverty.” But rather than seek “legislative solutions to the plight of the poor,” Boasberg advised that the modern lawyer “should first look closer to home, to judicial intervention, a tool which postdates Dickens by a century and was obviously unavailable to him.” (Emphasis added.)2

In Bleak House, the young Boasberg saw the Lord Chancellor—the judge presiding over Jarndyce—as someone who escaped “Dickens’ poisonous pen.”

Finding inspiration in the judge, Boasberg the student proclaimed that “we must move beyond the cabined, traditional view of a judge’s role as a mere resolver of a self-contained dispute between two parties about a past controversy.” Instead, Boasberg wrote, “we should conceive of judges more broadly as initiators of true institutional reform, inaugurating, or at least accelerating, the type of social change Dickens seeks but is unable to produce.” (Bolded emphases added.) To be sure, Boasberg’s article cabined this desire in modern terms—that “courts may intervene in an open-ended dispute among many parties to create a solution for a present problem” with a particular tool, “the structural injunction.” Fitting, then, that a “structural” remedy as we call it in antitrust—a breakup or divestiture in the form of an injunction—is what we imagine the FTC will seek, breaking up Meta, if it prevails in proving its liability case before Chief Judge Boasberg.

After more than six weeks of trial, which at times resembled Jarndyce, Meta’s fate now rests in the hands of the judge who wrote favorably of structural injunctions as a law student. Meta rested its case at the end of Week 6 of trial after calling its lead economist, Dennis Carlton, and the FTC rested its case for good after recalling its expert economist, Scott Hemphill, in rebuttal.

We look closely at those examinations in turn, but before we do, some cleanup: the FTC played video depositions for the media that weren’t aired in court. In the timeline of the trial, they were admitted in the FTC’s case-in-chief back in Weeks 4 and 5. But because these videos weren’t played in open court, we didn’t get to watch them until after trial finished. So we recap those first, before returning to the battle of the experts and weighing in on the trial as a whole.

Video Potpourri: DST, Morgan Stanley, Snap & LinkedIn

The four video depositions that the media saw were from third parties: DST Global, Morgan Stanley, Snap and LinkedIn.

The DST Global and Morgan Stanley video depositions were about WhatsApp, starting with Rahul Mehta of DST Global. We flagged earlier in the trial some uncertainty around DST Global’s ultimate investment in WhatsApp. The basics of what happened were explained by Mehta: DST Global was planning to invest up to $300 million into WhatsApp in February 2014—right as Facebook was negotiating to buy WhatsApp. After WhatsApp’s founders decided to sell to Facebook instead, Sequoia seemed to broker a deal whereby DST Global could buy a piece of WhatsApp anyway, at a lower total investment of around $125 million, at the same per-share price that Sequoia had paid. The upshot of all this, from the FTC’s perspective, was that WhatsApp didn’t need to sell to Meta to thrive; it had lots of takers, and DST could have ponied up even more money to help it. DST valued WhatsApp at $8 billion, far less than the $19 billion Meta paid for it, which the FTC argues is evidence that Facebook/Meta was paying a hefty premium for anticompetitive reasons. But Rahul Mehta agreed that WhatsApp’s founders had no intention of offering advertising, undercutting a key plank of the FTC’s theory; the founders wanted “people to pay for the provision of a messaging service much the same way you pay for gas [or] electricity.”

The next video was the deposition of Ali Esfahani, who was an investment banker at Morgan Stanley who worked on the WhatsApp deal. Back during the second week of trial, we had heard how Morgan Stanley was angling to advise WhatsApp. To Esfahani, WhatsApp was “a beautiful house” with many potential buyers. Because the deal was negotiated between Zuckerberg and WhatsApp co-founder Jan Koum, it “didn’t require an advisor because there were no negotiations involved,” and Morgan Stanley’s role was limited to “essentially reviewing the merger agreement” with lawyers. It was a “very unusual” deal in that it “went from soup to nuts over four days” that were “sleepless” and a “blur.” A Morgan Stanley deal deck had a slide titled, “Why acquire WhatsApp?” The rationale given: “WhatsApp Could Determine the Social Network Winner on Mobile.”

Prior examinations of witnesses from Snap were largely under seal, but we got to see the FTC’s version of the Snapchat story through its video deposition of Jacob Andreou, formerly Senior Vice President of Product and Growth at Snap. Andreou came across throughout the video as credible and without a dog in the fight. Recall that Snap matters because the FTC says it is within its proposed “personal social networking services” (PSN) market; Meta wants to use the presence of Snap in the market to show that other apps, like TikTok, YouTube, and iMessage, are inside the relevant market, too. Andreou is married to the British actress Carly Steel. If the below wedding photo looks overproduced, that’s because the photoshoot ran in People magazine:

The key feature of Snap’s app, Snapchat, is the disappearing message. Andreou called it a “transformative thing” that was meant to mimic real-life, in-person human communication. If you ran into someone on the street, “you don’t have a transcript of what was said”; an exchange happens without receipts. Andreou explained that Snap has a “hybrid friending model” that’s somewhere between bidirectional friending (as on Facebook) and the following/follower model (as on Instagram). If the friending on Snapchat is one-way, the follower can see the stories of the person they added, but it takes two to tango over messages, where reciprocal connection is required.

One questioner (and we couldn’t tell for which side, as they were off screen) asked if WhatsApp and iMessage offer the same group chat features that Snapchat does. “Some of the functionality is shared but some isn’t,” as “some competitors have less overlapping functionality and others have more.” Meta unified the messaging features across its apps, bringing disappearing stories—which Snapchat pioneered—into its product family. iMessage doesn’t have that feature, though. As for those disappearing stories on Snapchat, the “majority of your time [there] is spent with your friends, and then the next kind of large bucket after that is subscriptions, and the tail is ‘for you,’” or recommended content.

Then a questioner showed Andreou a 2022 Snap annual report. In a section titled, “Competition,” Snap said that it “compete[s] with” companies including Google, Apple, TikTok, Meta, and Twitter. Asked about those apps specifically, Andreou mostly answered that “parts” of Snapchat compete against some of these other apps, or that the other apps “to an extent” compete with Snapchat. And he added an answer that used the language of “two-sidedness”: “We competed either on the user side or on the advertiser side” with the apps listed in the document. One thing that differentiated Snapchat from Facebook is the privacy of someone’s Snapchat connections from other users, even though both apps are built around a “social graph.” There was lots of discussion around this feature and that feature, but you’ve now heard the gist.

Andreou also helped the FTC by explaining that, from Snap’s standpoint, increasing “ad load”—the percentage of all content impressions made up of ads—decreased user engagement. And, like Meta, Snap varies ad load. Andreou said it did so based on consumption and demand from advertisers, which means that ads vary mostly by different “age buckets in different countries.” The deposition ended on a cliffhanger with the revelation that Facebook tried to acquire Snap in 2012. The negotiations took place solely between Mark Zuckerberg and Snap founder Evan Spiegel, Andreou said.

Kumaresh Pattabiraman of LinkedIn was the last video deposition the media saw after trial ended. In rejecting Meta’s bid to end trial early in its favor, Chief Judge Boasberg made comments suggesting that really only TikTok and YouTube matter for market definition, which is where the parties spent most of their time. So we’ll skip over the mind-numbing details of LinkedIn features and uses. Yes, people can use LinkedIn to keep in touch with friends and acquaintances and the like, Pattabiraman explained. But the bottom line was that “although the line between professional and personal is increasingly blurred . . . LinkedIn and Facebook are also complements.” And product complements—products that you use together—are definitionally not economic substitutes, which are products that you use in place of each other. So it’s safe to conclude that LinkedIn is probably outside the relevant market here.

Meta’s Expert Economist, Dennis Carlton

That’s what happened in the out-of-time video depositions. But we left off the live trial with Nicholas Shortway. When he stepped down, Meta called its final witness, the expert economist Dennis Carlton. I had spotted him earlier attending the “tech tutorials” before trial.

Carlton is one of the leading defense-side economic experts working today and was a household name when I was at Cravath given his frequent appearances in big-time antitrust cases. Carlton testified for AT&T and Time Warner in the Department of Justice’s case to stop their planned merger, which the DOJ lost.3 He’s been a repeat player in FTC challenges to mergers in recent years, testifying for the defense in the proposed merger of Illumina and GRAIL (which resulted in an FTC win when Illumina divested GRAIL), as well as in support of Microsoft’s acquisition of Activision (which the FTC lost). Outside the courtroom, Carlton is the David McDaniel Keller Professor of Economics Emeritus at the Booth School of Business at the University of Chicago, a co-editor of The Journal of Law and Economics, and the author of more than 150 academic articles. He also served as the Deputy Assistant Attorney General for Economic Analysis at DOJ Antitrust during the George W. Bush administration.

Carlton is a man after my own heart as we both had the crazy idea to start boutique antitrust practices early in our careers. He was invited by the future Judge Richard Posner to co-found the economic consulting firm Lexecon when Carlton was just 26; he is still a consultant with that entity, now called Compass Lexecon. And he didn’t miss the opportunity to again mention basketball, an interest he shares with Chief Judge Boasberg. In one digression on the stand, Carlton explained that he became a fan of short-form TikTok videos “that teach you how to recover to play basketball again” while he was rehabbing a torn Achilles.

From Litigation Boutiques to the Meta Trial

Like Carlton, the young Jeb Boasberg took a chance on a boutique as a newly minted lawyer, fresh from his appellate clerkship in San Francisco in the early 1990s. Eschewing the large Wall Street-based firms known collectively as “BigLaw,” Boasberg joined the Frisco litigation boutique which is today known as Keker, Van Nest & Peters. I know the firm well from our defense at trial of Qualcomm against an FTC team that included its lead lawyer in the Meta trial, Daniel Matheson. It’s no surprise that the firm came to the defense of Chief Judge Boasberg after President Trump and Elon Musk called for his impeachment following his ruling concerning the wrongful deportation of individuals to El Salvador; name partner Elliot Peters said he’d “had it up to my gills with all these attacks on lawyers and judges.”

In 1995, Boasberg returned to Washington, D.C. And again, he bet on another litigation boutique, this one founded just two years earlier, and which today goes by Kellogg, Hansen, Todd, Figel & Frederick—the firm that has been defending Meta in this trial. Name partner Mark Hansen, of course, is Meta’s lead lawyer. Although Chief Judge Boasberg’s time at Kellogg Hansen has long been public record, this blog was first to report the connection before the Meta trial began.

Messrs. Kellogg and Hansen rarely if ever sit for interviews. A 2021 Business Insider story on the firm’s representation of Saudi royals noted that Michael Kellogg had only given one interview ever. But what little can be gleaned from the public record suggests that the relationship between Hansen and Chief Judge Boasberg was a meaningful one.

We know that they worked on cases together. The two defended a health insurance carrier, Healthplus, in the Eastern District of Virginia in 1995. That was an Americans with Disabilities Act case where the plaintiff alleged that a physician referred by Healthplus refused to perform surgery on her because she was HIV positive. In another case, in Maryland federal court, Hansen and Boasberg represented a health insurer as a third party seeking to quash a subpoena to produce personnel files in a purported antitrust suit from a doctor; their motion was denied. We presume that the Chief Judge met the other young lawyers who started at the firm in 1995: among them, Neil Gorsuch, now a Supreme Court Justice, and Geoffrey Klineberg, another member of Meta’s trial team who recently served as president of the D.C. Bar. I saw Chief Judge Boasberg and Klineberg chatting for a few minutes outside the courthouse near the end of trial.

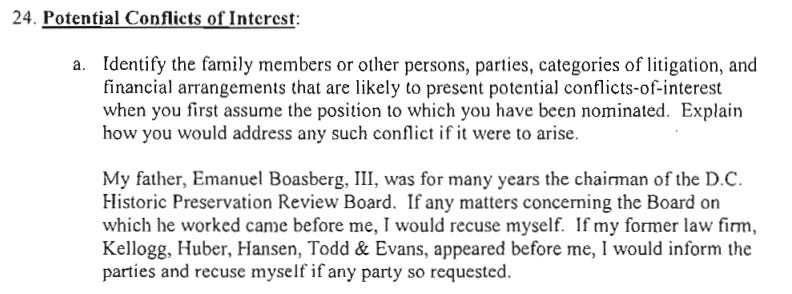

After his yearlong stint with Kellogg Hansen, Boasberg became an Assistant United States Attorney for the District of Columbia, prosecuting murderers. And from 2002 until his appointment to the federal bench, he was an Associate Judge in D.C. Superior Court, the “state”-level court for the District. You might not think that working as an associate for a year would be enough to a form a long-lasting bond. So it was interesting that, when President Obama nominated Boasberg for his current seat on the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia in 2010, the judge nevertheless offered to recuse himself from matters involving Kellogg Hansen, even though he had not worked there in some 14 years:

We have not sought comment from the parties or searched the docket for whether Chief Judge Boasberg offered to recuse himself from this matter. But he was not the initial judge on this case. State Attorneys General filed a parallel suit against Meta alongside the FTC back in December 2020, with some differences. The State AGs’ case landed before Judge Boasberg, and the FTC’s case was on the docket of Judge Christopher Cooper.

By the next month, though, the FTC’s case was reassigned from Judge Cooper to Judge Boasberg:

Reassignment of related cases before a single judge isn’t unusual. What is a little strange is that, while the FTC and the State AGs seemed to be coordinating on filing their cases on the same day—December 9, 2020—they didn’t initially mark their cases as related. Under the court’s local rules, “[w]here the existence of a related case in this Court is noted at the time . . . the complaint is filed, the Clerk shall assign the new case to the judge to whom the oldest related case is assigned.” Instead, both the FTC and AGs waited two days before each filing something noting the existence of the other case. What’s supposed to happen in those circumstances? The local rules say that the “judge having the later-numbered case may transfer that case to the Calendar and Case Management Committee for reassignment to the judge having the earlier case.” In the cases against Meta, though, the States forced the issue by moving before Judge Boasberg to consolidate the cases before him. Did that mean that the plaintiffs tried to get a preview of the judge assignments before seeking consolidation? And that they reckoned that Judge Boasberg was a better bet for them? Meta opposed consolidation for all purposes, but didn’t object to both cases being before Judge Boasberg. In the end, the FTC’s case moved over to Judge Boasberg’s docket because it was the “later-filed” case—by a single digit, as the FTC’s case number ending in 3590 came just after the States’ ending in 3589; they were filed back to back.

Carlton on Market Definition and Monopoly Power

And so, nearly five years after filing, it was Chief Judge Boasberg presiding over the FTC’s trial against Meta. Kellogg Hansen’s Aaron Panner, who had some of the more important assignments at trial, including examining TikTok witnesses, handled Carlton’s direct. (Both Carlton and Hemphill’s examinations were strangely reliant on the experts reading verbatim the words on their demonstrative slides.)

Carlton had three main opinions: (1) "[t]he economic evidence is inconsistent with any claim that there is a relevant product market for personal social networking services limited primarily to Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat”; (2) "[t]he evidence does not support that Meta has monopoly power in a relevant product market that includes TikTok or YouTube"; and (3) "Meta's acquisition of Instagram and WhatsApp did not cause consumer harm, and on the contrary, they produced clear consumer benefits compared to the likely outcome in the but-for world.”

Carlton’s key point on market definition was that, looking at natural experiments such as TikTok bans and service interruptions in Meta’s apps, more substitution happens between Meta’s apps and TikTok and YouTube than happens between Meta’s apps and Snapchat, meaning that if Snap is in the PSN market, as the FTC claims, then TikTok and YouTube should also be in the market. In addition to the quantitative substitution data, Carlton also found it important that these apps all compete “for the same creators of video content” and sometimes copy each other’s features (like short-form video and disappearing stories). He savaged Hemphill for dismissing quantitative evidence and instead relying on what Carlton called Hemphill’s “[f]ocus[] on a use case to guess consumer substitution.”

Let’s start with the “direct evidence.” And if you need a refresher on direct and indirect evidence or any of the other bolded terms below, we defined those here and here. The idea here is that a structural market definition and calculation of market shares might be unnecessary if the FTC can show direct evidence of monopoly power, like Meta’s ability to profitably and durably raise prices above - or degrade quality below - the competitive level. And Carlton pointed out all the problems with Hemphill’s attempt to offer direct evidence: “the actual price is zero” for Meta’s apps, and while Hemphill tries to show price discrimination using a “quality-adjusted price” (here, ad load), Carlton characterized Hemphill as in effect saying “it’s too hard . . . to come up with an index of the quality-adjusted price, so instead, [he] . . . focus[ed] on quality characteristics” like latency, privacy, and so on. But those quality traits are “common characteristics” not specific to the friends-and-family sharing use-case that is at the core of the PSN market, Carlton said. Likewise, Carlton highlighted that Hemphill is “not willing to say that market output is lower today than it would otherwise have been” in the but-for world where the Instagram and WhatsApp mergers never happened, nor does Hemphill opine “that compared to the but-for world, R&D would be different and that Facebook would have invested more or there would have been more R&D in the market as a whole.” With all of those difficulties, it’s not surprising that the FTC’s opening started with indirect evidence, as Hemphill did in his testimony.

Turning back to natural experiments, Panner and Carlton discussed a time in 2021 when Meta’s apps went offline temporarily. TikTok and YouTube were the top two apps where Meta users turned during the blackout. And Reels—the short-form video feature on Meta’s apps—was only rolled out in 2021. More recent data from the brief time TikTok was offline because of the “ban” in the United States showed that Instagram usage increased around 40% in that period, Carlton said.

Panner confronted Carlton with Hemphill’s point that this experiment doesn’t fit the Hypothetical Monopolist Test (HMT), which asks whether a hypothetical monopolist of all products in the candidate market could profitably impose a Small but Significant and Non-Transitory Increase in Price (SSNIP). Carlton readily agreed that an app going offline is “more like an infinite price increase” than a 5% price or quality change (the SSNIP threshold commonly used in the HMT.) But he said this didn’t matter because he’s just showing that consumers are more often going from Meta’s apps to TikTok and YouTube than to Snapchat—sometimes “four or five times as many consumers”—meaning that if Snapchat is in the market, YouTube and TikTok have to be. Carlton isn’t claiming to do the HMT test, and he disputed that Hemphill was actually doing one either because they had “no data” to model a 5% quality-adjusted price increase: “He just claims these three firms are in the market and [that he] think[s] they satisfy” the HMT, Carlton said.

Carlton parried the “cellophane fallacy” criticism in a similar way. Recall that the “cellophane fallacy” is testing whether the hypothetical or candidate monopolist can impose a SSNIP from a price that is already above the competitive level, rather than measuring from a competitive baseline; making this error tends to define a market too broadly. Carlton called this “a correct caveat” but one that “is not a criticism of what I’m doing, because what I’m doing is the relative substitution[:] is YouTube and TikTok, are they more important than Snapchat by a lot, and the answer is yes.”

Carlton also tried making the point that Facebook and Instagram are more about video-sharing. He showed data that, as of January 2025, Reels makes up the majority of time spent on those two apps. He also discussed another experiment where Meta “dialed down” the availability of Reels by roughly 80%, finding that users spent about 25% less time on Instagram with less access to Reels. The implication from the latter experiment was that users are spending more time on video, but the drop-off wasn’t 1:1 correlated, not even close. If Carlton’s broader takeaway were true—Instagram is for video—you’d expect to see something closer to an 80% drop-off in time from an 80% reduction in access to Reels. Putting all the data together, it suggests that people might be enticed or distracted by the presence of Reels, but that they would continue using Meta’s apps for their other purposes (read: friends and family sharing) even if Reels did not exist.

A stronger point was that friends and family sharing was down to 17% of time spent on Facebook and 7% of time spent on Instagram as of January 2025. But the FTC pointed to problems with these calculations on cross, namely, that the numbers shown here are only percentages of time, not absolute time. In other words, suppose a user spends two hours a week catching up with friends on Facebook, both in 2015 and in 2025. And suppose they spent an hour a week watching video on Facebook in 2015, but in 2025, they spend four hours a week watching video on Facebook. In 2015, their percentage of time spent watching video on Facebook would be 33%, and in 2025, it would be 80%. But that doesn’t mean that they’ve abandoned the friends-and-family use-case at all. In rebuttal, Hemphill offered a variety of data proving up that the growth of short-form video hasn’t come at the expense of the traditional friends-and-family sharing “surfaces,” Feed & Stories:

Carlton also took issue with Hemphill’s data showing that time spent on Instagram and Facebook spikes on holidays because time spent on other apps spikes during holidays, too. And Carlton said that it would make sense for ad load to spike during holidays as well if Hemphill’s theory that Meta shows more ads to people who use its apps for friends and family sharing were true; but in fact, ad load drops during holidays.

Milk and Cookies

Carlton next disputed the idea that Meta can in effect “price discriminate” by showing more ads to users who have a higher demand for friends and family sharing. He testified that competition with other apps (TikTok and YouTube) for time spent watching video “will protect those people who have a higher dependence” on Meta’s apps for friends and family sharing.

To illustrate his point, Carlton introduced a hypothetical case of price discrimination for cookies made without milk between consumers who are and are not allergic to milk. Even though consumers allergic to milk might have a greater demand for cookies made without milk, if 80% of buyers of “cookies without milk” switch to “cookies with milk” in response to a price increase, that will discipline the maker of “cookies without milk” from raising prices and exploiting the lactose intolerant customers who need those cookies. Bringing the analogy back to the case at hand, Carlton claimed that since the majority of time spent on Facebook and Instagram is for watching videos, and because there’s competition for watching videos, that will protect even the consumers who aren’t watching videos, and who are instead using Meta’s apps to connect with friends and family. But this was another non-empirical, “you gotta figure” explanation that was a little hard to follow—along with the assumption that 80% of buyers of non-lactose cookies have no milk allergy.

A final argument from Carlton on price discrimination was that another of Hemphill’s quantitative opinions—resulting from what’s called a “regression analysis”—didn’t show a link between demand for friends and family sharing and ad load. Most saliently, people with more Facebook friends see fewer ads, not more. But it’s hard to say why having more Facebook friends necessarily meant having a greater demand for seeing that content vs. video content. At the same time, younger users of Facebook and Instagram have a lower ad load even though they spend more time on friends and family sharing than older users, who see more ads.

Carlton on Anticompetitive and Procompetitive Effects

The direct finished up with anticompetitive effects. Output increased after the Instagram and WhatsApp acquisitions, generating billions of dollars in consumer surplus, Carlton claimed, noting that Hemphill didn’t provide any opinion on how output would be different in the but-for world where Instagram and WhatsApp stayed independent. Carlton called the Instagram deal a “grand slam home run.”

We saw various attempts to substantiate the claim that “output” increased—more users, more time spent, and more features being introduced post-acquisition. Everybody seems to agree that Instagram and WhatsApp improved over time, and the FTC’s claim is that they would have improved even more on their own.

Using a variety of sources, including what appeared to be estimates from other Meta experts who we did not see testify, Carlton pegged the annual consumer surplus from the Instagram acquisition between $12.9B and $78B; from WhatsApp, the range was $25B to $31.5B. Carlton said that in the but-for world without the acquisitions, Instagram and WhatsApp would be smaller, and total output would be lower. “That’s bad for consumers, not good,” because Meta would be less incentivized to invest in quality improvements. “The larger the output you’re selling, the greater the incentive to improve because the improvement then goes across all the units and you can charge for it,” Carlton testified. After that, testimony continued in a courtroom closed to the public for confidentiality reasons.

At certain points in this direct examination, Panner seemed to be frustrated with Carlton’s tangents and mistakes in word choice. A few times Panner asked if Carlton meant to say X, or showed him that the demonstrative slide measured something different from what he was talking about.

Cross of Carlton

The FTC’s Krisha Cerilli, Deputy Assistant Director of the Technology Division, cross-examined Carlton. She began by getting Carlton to agree that firms can compete at a broader level without competing in the same relevant antitrust market or submarket. The parties have at various times used the word “submarket” to describe the PSN market and/or the friends-and-family-sharing use-case for Facebook and Instagram. But Carlton explained that the “submarket” concept—taken from the Supreme Court’s Brown Shoe case—is not really helpful. Since the HMT defines the narrowest relevant product market in any event, the “submarket” idea doesn’t introduce something unique. This is one of those areas, like the distinction between monopoly power and market power, that is more a vestige of old case law than a principle of modern antitrust economics.

Cerilli next laid a deadly trap that Carlton walked right into:

Q. You did not attempt to assess the purposes for which consumers use different apps?

A. That’s fair. I looked at the actual evidence of substitution.

What makes this important is the language from the Microsoft case that Chief Judge Boasberg cited at the summary judgment stage: the defined market must include “all products reasonably interchangeable for the same purposes.” As the court put it, citing another case, “courts look at whether two products can be used for the same purpose, and, if so, whether and to what extent purchasers are willing to substitute one for the other.” And so Carlton’s concession that he didn’t analyze the purpose for which consumers used Meta’s apps hurts his study of substitution. Perhaps there is substitution among short-form video products, but Carlton didn’t look at the extent to which consumers are engaging in friends-and-family sharing on non-Meta apps. What’s more, Carlton agreed that simply looking at substitution between two products doesn’t answer the question posed by the HMT: whether that substitution is happening in light of a SSNIP.

The rest of cross helped establish some modest points that help the FTC’s theory of the case, where Carlton agreed that a monopolist can degrade quality at a price of $0, that efficiencies and claimed consumer surplus must be merger-specific, and that even monopolists may do things like invest in R&D and introduce new features. So the laundry list of product improvements that Meta made doesn’t say much one way or another as to whether it is a monopolist.

After cross concluded, Meta rested its case.

Hemphill’s Rebuttal

The case resumed with the FTC’s rebuttal, in which it recalled one witness: its economist, Scott Hemphill. Cerilli was tapped again for the direct. Here was the gist:

Hemphill started off by describing his task with the HMT as asking whether a single firm controlling Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat, and MeWe in the United States could profitably set a lower quality level compared to the competitive level. The studies from Meta’s Carlton and John List showing substitution between Meta’s apps and TikTok and YouTube flunked the “small but significant” and “non-transitory” components of the SSNIP test, as Carlton admitted and we previewed back on the first day of trial. Hemphill said this was focusing on the wrong substitution, like “losing your keys and seeking illumination under the lamp post—the data isn’t providing illumination to the question at issue.”

One interesting citation that followed was quoting Google’s expert economist from the Search antitrust trial (which it lost), Mark Israel, for the proposition that the HMT is often qualitative rather than quantitative.4 Here’s a helpful diagram from Hemphill’s slides about why the substitution experiments have limited import:

Another analogy Hemphill offered on the outage studies was having your car break down. You might take the subway, walk to work, or work from home in that event. But it would be strange to think of walking, staying home, and riding the subway as part of the same antitrust market as cars.

Hemphill got ahead of his skis, though, in claiming that “outages do not meaningfully inform business decisions” by selectively quoting testimony from Adam Mosseri, Head of Instagram. Meta hammered him on cross for ignoring testimony from Mosseri to the effect that the outage data did drive business decisions at Meta and encouraged them to double down on short-form video. That helped Meta’s point that Hemphill wasn’t a neutral expert but was instead cherry-picking to support his “preconceived notions.”

The direct then moved to price discrimination. Price discrimination can sometimes show monopoly power, but it’s usually not enough standing alone to show monopoly power because firms in a differentiated product market may enjoy some lesser degree of market power that allows them to price discriminate in some way. For Hemphill, Carlton didn’t dispute that Meta engages in a form of price discrimination by varying ad load for different users, disputing only whether that was connected to demand for friends and family sharing. In all events, Meta can and does vary ad load based on age, a user’s sensitivity to seeing ads, friend count, the age of the account, and by surface, differing ad load across Stories, Feed, and Reels.

After offering data refuting the idea that friends-and-family sharing has declined (covered above), Hemphill rebutted Carlton’s “milk and cookies” hypothetical that competition for unconnected and video content disciplines Meta’s ability to exploit users who like friends-and-family sharing. What might be true in theory was false in practice, Hemphill explained, showing that ad load increased even as user sentiment for ads declined. That’s evidence of monopoly power, and it’s evidence of anticompetitive effects. And unlike the protestations from Meta witnesses that the user surveys are just signal noise based on news cycles, these findings seemed to be durable over a 5-year period:

Turning to anticompetitive effects, Chief Judge Boasberg jumped in to ask about “output,” a term that Carlton had thrown around a lot without being clear about what exactly he was measuring the output of. The court asked if the number of users was the key measure. Hemphill disagreed; the “coin of the realm” is consumer surplus, he said, the amount of value consumers receive from Meta above what they pay (here, nothing). The court offered that looking at output seemed easier than looking at quality because the consumer sentiment metric can be influenced by current events, and called other quality indicia “amorphous.”

After Hemphill had finished with his slides, Chief Judge Boasberg took over the questioning. He started with the idea that Meta overpaid for WhatsApp for anticompetitive reasons. Wasn’t that logic in tension with the Instagram acquisition price of $1B, which seemed to be too low? Hemphill cited the Sequoia analysis valuing Instagram at only $500 million at the time. The court also wondered again how output could be even higher on Instagram in terms of the number of users given that there are not many more users to add in the United States; Hemphill responded that the court should still look at time spent, the friends and family content shared, and other metrics to see how users spend their time once they’re on the app (which could have been higher in the but-for world if Instagram wasn’t acquired by Meta).

A Biased Expert?

In addition to hitting Hemphill for seeming to disagree with testimony from Meta’s Sheryl Sandberg and Adam Mosseri, the cross-examination—this time conducted by Kevin Huff—focused on Hemphill’s purported “roadshow” with Tim Wu to federal and state antitrust enforcers about the potential merits of an investigation into Meta’s Instagram and WhatsApp takeovers. Our writeup from Hemphill’s direct in the FTC’s case-in-chief earlier in trial flagged that Meta had left on the table a Medium post Wu and Hemphill co-authored and published the day after the FTC brought this case against Meta. This time around, Huff used the post—published years before the FTC retained Hemphill as its expert—to again cast his conclusions as “preconceived.” These were the key lines from the post:

There are enormous differences between the Instagram and WhatsApp acquisitions and the thousands of other deals in tech or elsewhere. These were acquisitions that were:

(1) by a monopolist;

(2) of its direct competitors or nascent competitors;

(3) with abundant evidence of anticompetitive intent.

After a brief re-direct, where Hemphill explained that he didn’t have any conclusions at that time in 2019-2020 and was only suggesting that the acquisitions might warrant investigation, the FTC rested its case. Meta then announced that it would file a short motion to exclude Hemphill’s testimony based on this evidence of “bias”. That briefing finished after trial, and the court denied Meta’s motion in a short order explaining that the court would consider this in deciding how to weigh Hemphill’s testimony, but would not exclude it outright.

There were no closing statements; instead, the parties will file post-trial briefs, and Chief Judge Boasberg may have a hearing if he needs any follow-up. The court said to expect a ruling soon after briefing concludes, so I would predict a decision before the end of the year.

Putting it All Together

One question I’ve been asked throughout my coverage of this trial is the $64,000 one: who do I think will win? The answer really turns on what the court already decided at the summary judgment stage. There, the court thought that market definition would be “pivotal” to the case.

As for anticompetitive effects, the court determined that “a monopolist’s acquisition of an actual or nascent rival is itself an anticompetitive action, regardless of any price or output evidence.” (Emphasis added.) As the court explained, “price- or or output-related evidence of competitive harm is downstream from the anticompetitive effect itself,” and plaintiffs need not "separately show consumer harm”—they just need to show that the challenged conduct “maintained a monopoly other than through ‘competition on the merits’ and thus presumably harmed consumers.” (Emphasis added.)

On the other hand, the court also explained at summary judgment that the test for procompetitive justifications, which Meta can use to rebut the FTC’s claimed anticompetitive effects, is “notably more forgiving” in a Sherman Act monopolization case, as compared to a Clayton Act merger challenge, although the standards are not “dramatically” different. Meta can meet this burden by showing that a merger “increased output, decreased prices, improved service or quality, spurred greater innovation, or the like.” Still, the court explained that the procompetitive benefits must flow from the “least restrictive” means for achieving them. Put another way, the efficiencies must be specific to the mergers. If Meta makes this showing, the burden shifts back to the FTC to show that the anticompetitive effects outweigh the procompetitive justifications.

That boils the case down to three issues: (1) Is Meta a monopolist? (2) Were Instagram and WhatsApp nascent threats? And (3) If they were, did the acquisitions offer greater procompetitive benefits than anticompetitive harm?

The easiest part to make a prediction about is WhatsApp. I don’t think the FTC carried its burden to show that WhatsApp was an actual or nascent competitor to Facebook. Most evidence adduced at trial—from Sequoia, WhatsApp’s founders, and from Meta itself—showed that WhatsApp did not have ambitions to branch out into a personal social network or to monetize through advertising, which the FTC is trying to show WhatsApp would have done to demonstrate its viability as a standalone business without needing Meta’s money to succeed.

The FTC’s WhatsApp case largely rests on inferring that WhatsApp was a nascent competitive threat from the other chat apps that branched into social networking features like WeChat and Kakao. But even Meta’s internal presentations on these apps carefully distinguished WhatsApp as having a different strategy. Somewhat frustratingly, Meta announced—after trial ended—that it would now be introducing ads on WhatsApp! The FTC might have been right about this point all along, but it didn’t have the evidence at the time of trial that Meta was secretly planning to monetize WhatsApp. And the FTC seemed to recognize it was going to lose the WhatsApp part of its case by the end of trial, barely spending time on it in Hemphill’s rebuttal examination.

That leaves the Instagram theory of monopolization. On market definition, the court already suggested that the fight is about whether TikTok and YouTube are part of the PSN market; more distant putative competitors like LinkedIn, Strava, and Pinterest probably don’t matter all that much. For Meta to win at the monopoly power stage of the analysis, it needs to win that both TikTok and YouTube are in the same market with Facebook and Instagram. That’s because adding just TikTok doesn’t reduce Meta’s market share enough—it takes it down to 60%. Despite Carlton and Meta continually claiming that 60% is not enough to show monopoly power, that is not a complete and accurate statement of the law. A 65% market share indisputably shows monopoly power, but a lower market share in some cases could, too, as we’ve repeatedly covered by citing cases that say that. A 50% market share is good enough. And adding TikTok plus YouTube to the market together takes Meta’s market share below 30%, which is probably not enough for the FTC to prevail.

Throughout trial, Chief Judge Boasberg seemed interested—if not persuaded—by the evidence of substitution between Facebook and Instagram on the one hand and TikTok and YouTube on the other. But Hemphill and the FTC did a good job pointing out all the problems with those “experiments” or outages. But remember, Meta doesn’t have to prove anything; it’s the defendant. It’s the FTC’s burden to show that it is more likely than not that Meta is a monopolist. Disproving Meta’s attempts at disproving market definition isn’t the same thing as proving market definition. And on that latter score, Carlton was persuasive that Hemphill didn’t have a competitive baseline quality-adjusted price from which to impose a SSNIP that could satisfy the HMT. Hemphill admitted as much in rebuttal, and he and the FTC fell back on the idea that the HMT can be qualitative.

As the court explained at summary judgment, a “qualitative” HMT is largely coterminous with applying the submarket definition factors from the Supreme Court’s Brown Shoe decision. Those factors include things like “industry recognition” of the market as distinct and the “peculiar characteristics and uses” of the products in the proposed market. It’s difficult to predict how the Brown Shoe factors come out as industry recognition cuts both ways. On the one hand, much of the evidence seems to recognize that there is something called “social media” or “social networking” and that Meta’s apps do that function. But on the other hand, numerous internal documents, both at Meta and from other companies, seem to contemplate competition for short-form video or for “time and attention,” as Meta puts it. Still, the idea in all cases is to define the narrowest market, and so evidence of competition at a higher level of generality doesn’t doom the FTC’s PSN market definition.

The FTC wants to get around these problems by using evidence of increased ad load as direct evidence of monopoly power, but I think not dealing with the “two sides” of Facebook and Instagram was a strategic mistake on that front. Recall that a two-sided market is one where the customers on one side of the platform affect customers on the other side of the platform; for Facebook and Instagram, there are account-holders on one side and advertisers on the other side. Higher ad load might be worse for users and at the same time might reflect lower ad prices on the advertiser side of the market.

As we’ve covered, there’s some reason to think that ad prices on Meta’s apps increased. True, as the Supreme Court said in the American Express case, looking at prices on both sides of a two-sided market isn’t always necessary, and it specifically pointed to advertising as a classic example of a situation where that level of analysis isn’t needed. Many markets could be considered two-sided to some degree, and the question is how much that matters for evaluating conduct in a particular case. But Hemphill didn’t really do anything to figure out if this is one of those cases where two-sidedness matters or not. And he didn’t have much to say about that in rebuttal. There might have been a stronger case there to point to increased ad prices and increased ad load as conclusive proof of Meta’s monopoly power. But for whatever reason, the FTC didn’t present that case.

The FTC may have had other ingredients available to determine a competitive level of ad load, too. It could have dealt with the problem of finding the competitive level of ad load and the problem of two-sidedness by using what’s called the “yardstick” approach—looking at an analogous market that’s not monopolized to see what the ad load is there. But it didn’t do that, or, at least, it didn’t introduce evidence of that at trial.

But let’s assume that the FTC wins market definition by a hair for the friends-and-family sharing use case, and that at least YouTube is outside the PSN market. The tougher case for the FTC is winning the balance of anticompetitive effects. Yes, the FTC had a light load to show the initial anticompetitive effect because there was some good evidence that the goal of acquiring Instagram was to take out a potential competitor. And under the logic of the court’s summary judgment ruling, that’s all the FTC needs to show at step one.

That’s where things get complicated. At step two, Meta has to show a procompetitive benefit from the merger. The Court explained at summary judgment that that claimed benefit can’t be pretextual. And it added another wrinkle: that Meta must prove the acquisition of Instagram was the “least restrictive alternative” for achieving the same procompetitive benefit. In support of that rule statement, Chief Judge Boasberg cited a controlling case under Section 1 of the Sherman Act, which concerns agreements in restraint of trade, rather than the monopolization claim under Section 2. But he noted disagreement between the courts on that point of law. In the appellate court decision from Epic Games’ antitrust suit against Apple’s App Store (and I worked on that case for Epic at an earlier phase), the Ninth Circuit called it the plaintiff’s burden to rebut that procompetitive benefit by showing that there are less restrictive alternatives.

And whose burden it is to show the “least restrictive alternative” might make all the difference. If it was Meta’s burden to show that Instagram wouldn’t have captured those procompetitive benefits if it hadn’t been acquired by Meta, then Meta will probably lose the case on the Instagram theory. But if it was the FTC’s burden to show some other alternative that would have been just as good, it likely came up short.

Meta did a decent job showing all the ways in which the acquisition helped Instagram grow. Everybody seems to agree that Instagram grew more quickly after Facebook bought it. And Hemphill couldn’t say that Instagram’s growth was slower than it otherwise would have been had it never become part of Meta. Bushwhacking through the nitty gritty weeds about whether Amazon Web Services could have led to the same growth for Instagram, such that the claimed benefit wasn’t merger-specific, is a tough place for the FTC to be in, given that Hemphill can’t say that Instagram would have done the same or better in the but-for world.

Even if total ad load would have been lower in the but-for world without the acquisition, that’s just one factor among many ingredients that go into “quality.” And while Hemphill and the FTC pointed to a litany of other “quality” components, the court called this “amorphous” and difficult to pin down. Why should ad load count more than reducing spam, for example, when thinking about whether Meta improved Instagram’s quality? Hemphill and the FTC never gave us a reason why. And that doesn’t rebut Meta’s claimed justification(s) as pretextual or outweighed by the harm of just acquiring Instagram.

In the end, the frustrating part of this case is that Meta has a good chance to win, even though most of its arguments are economically unsound. The case is a lot closer than it was made out to be in the press and antitrust community before trial. And that’s often why cases go to trial: strong and weak ones get settled early. Close calls go to trial. And this is an exceedingly close case on market definition and anticompetitive effects/procompetitive justifications.

At the end of the day, a tie goes to the defendant. The FTC had the burden to be ahead by a hair. It might just meet that burden under Chief Judge Boasberg’s ruling that it’s the defendant’s burden to prove the procompetitive justifications were specific to the merger and couldn’t have happened another way. Make that the FTC’s burden, though, and the agency probably didn’t devote enough time or introduce enough evidence—or more importantly, a theoretical framework for weighing it—that overall quality has declined because Instagram became part of Meta, and not enough to show that all the quality improvements on Instagram could have happened some other way. In any event, the FTC has the ultimate burden of proof to show that anticompetitive harm outweighed procompetitive benefits. And on that score, it’s not enough to blow up the other side’s case with a bazooka. As the plaintiff, you have to build and prove your case.

What to Take Away

If the FTC loses this trial, the inevitable commentary will again point to FTC “overreach” and be used to indict the pro-enforcement mentality that the Biden antitrust appointees—FTC Chair Lina Khan and DOJ Antitrust head Jonathan Kanter chief among them—brought to the job. But I don’t think these criticisms are correct or fair. Remember that this case was brought by the first Trump administration. And the FTC showed in this case that it did have the outline of a viable theory of harm that survived dispositive motions. Its theory was legally sound. But at trial, a theory is not good enough. A theory of harm, a model of harm, doesn’t cut it—the FTC has to show actual harm. If it came up short, it failed on its proof, not on its conceptual validity.

If the FTC loses, it will also highlight the need to challenge mergers as they happen, not years later in retrospect. This would have been a slam dunk case for the FTC at the time of the Instagram acquisition with the emails that were in the record. In a prospective challenge to a merger under the Clayton Act, the standard is easier to meet, focusing on likely anticompetitive effects, rather than actual anticompetitive effects. There wouldn’t be a record of Instagram’s explosive growth post-acquisition or anything about how Meta helped Instagram fight spam or improve latency because that wouldn’t have happened yet. Back in 2012, TikTok did not even exist.

As the court said at summary judgment, the Sherman Act standard for procompetitive justifications is easier to meet than trying to show efficiencies in a Clayton Act merger challenge. It’s agonizing that the FTC whiffed on a home run case 13 years ago and then had to devote probably millions of dollars in resources to righting that wrong with a worse evidentiary record. That is not an indictment of today’s FTC; it’s an indictment of the under-enforcement that prevailed in the Bush and Obama administrations.

Finally, it’s vitally important to go to trial, even if the FTC loses some cases. One problem the agencies face is that for about 20 years after the Microsoft case, there weren’t many monopolization cases brought by the government and tried to judgment at all. And there is no better way to train staff to be prepared to take cases to trial than to take cases to trial. Matheson and other senior FTC officials did not hog the spotlight; they spread the opportunities to examine witnesses around a big team of young lawyers, some of whom we imagine got their first experience examining a witness in an antitrust case at this trial. If you settle everything that comes along with slap-on-the-wrist commitments and nothingburger divestitures, you’ll never get a trial-ready team that strikes fear into the hearts of merger parties or monopolists. And so you’ll keep getting weak remedies and under-enforcement.

While it does make sense that, given how close the evidence was, a trial was needed to resolve this case, the FTC’s reported demand for $30 billion from Meta to avert trial with a settlement doesn’t make sense at all in a case where the FTC isn’t seeking damages or disgorgement. Increasingly the FTC is showing that it is either beholden to President Trump—and his purported firing of the Democratic commissioners and the challenge to longstanding Supreme Court precedent holding that the President can’t do that underscore his influence—or pushing some kind of you’ve been mean to me conservative grievances about censorship. In other words, Chair Ferguson’s statements complaining about censorship—and recall that Meta stopped circulation of the Hunter Biden laptop story and banned Trump from its platforms—combined with his reported demand for a pound of flesh for a close case make it seem like politics was driving this case, at least in the time since Trump took office again. And if that’s true, it’s a great disservice to the American people and to the staff that worked so hard to prepare this case and try it to judgment.

Another sign that could and should have been given more consideration in the decision to press ahead with this case and make bold settlement demands was that the FTC’s original expert economist, Carl Shapiro, reportedly left the case back in 2021, as a reader of the blog pointed out. The consulting firm he works with, Charles River Associates, stayed on to support Hemphill, who testified that he wasn’t hired until 2022. Having your lead expert leave is a bad sign. It’s a yellow light that should make enforcers slow down and think about whether this is the right case or whether it’s being built in discovery in the right way. We don’t know why Shapiro left, but it wouldn’t be unreasonable to guess that he didn’t or couldn’t opine in a way that supported the FTC’s theory of the case. The FTC knew what Hemphill thought from his “roadshow,” so he was a safer choice—but not the first choice, since that roadshow featured prominently (if not effectively) in Meta’s cross-examination to support a theme that he cherry-picks favorable evidence. And with all due respect to professor Carl Shapiro, he isn’t exactly the world’s most demanding expert. He was the FTC’s expert economist in the Qualcomm case, where he, like Hemphill, relied on qualitative theory over empirical analysis; the district court ruled for the FTC but did not cite Shapiro’s testimony at all before the Ninth Circuit vacated the ruling. If even this Meta case is too far afield for that expert, it’s saying something.

Meta may win this trial, but it sure felt while watching that it didn’t deserve to. Meta’s lawyers—Mark Hansen in particular—were often sarcastic and condescending and objected too strenuously to minor issues. Hansen was humble enough to sit on the back bench and likewise spread the opportunities to speak at trial among a large team, which eventually included more women attorneys and younger lawyers as trial went on. Meta’s witnesses similarly needed a reality check, thinking they could tap dance around statements we just heard them say or venture into hawking their forthcoming books. It’s fair to say that some didn’t take this trial seriously at all; they seem to see it as a game, just another opportunity to blow everyone away with their smarts and charm. But most of what Meta’s witnesses said didn’t amount to a hill of beans. In the end, the case will live and die with Hemphill.

And I worry that Meta will have a false sense of confidence if they win this case and be emboldened with a new feeling of impunity. Meta is now introducing AI products that, given its history of potential harm to children and teenagers, raise significant concerns. Meta could do a lot more to address those problems than it has been doing, but chooses not to. And it’s able to choose not to because it doesn’t have sufficient competition to make it behave better. Just because it may not be found a monopolist at trial doesn’t mean that it isn’t one in the real world.

The real world is where we all live. The original promise of Facebook was to connect through the Internet people who know or should know each other in the real world. But rebranded as Meta, referencing a “metaverse,” it is increasingly building a virtual world. Rather than introduce people who share your interests in your neighborhood, Meta seems more concerned with building AI chatbots to replace your real-world relationships. It’s a strategy that might not be anti-the-antitrust-laws. But it’s one that’s profoundly anti-human. Meta is now recognizing that it strayed too far from what brought people to its products to begin with, rolling out features like the “friends” tab (available only on mobile devices) so you can see posts from your friends instead of scrolling through 10,000 items to find them. But it’s fair to wonder whether its pivot back comes, like this antitrust trial, a decade too late.

Now, the fate of Meta rests in the hands of the judge who as a law student hoped for an opportunity to impose a “structural injunction.” He now has the chance to do so against the company represented by his former boss and colleagues. In the end, though, the case isn’t likely to turn on these old relationships and musings. It won’t turn on the FTC’s theory of harm, which the court already endorsed as legally sufficient. It will turn, as all trials do, on the evidence. While there probably wasn’t enough evidence to find that Meta’s acquisition of WhatsApp broke the antitrust laws, the FTC has a fighting chance on the Instagram story.

We won’t make an ultimate prediction on that score. Instead, we leave you with what Meta’s new AI chatbot predicted—that “Meta’s likelihood of losing the FTC’s antitrust case seems high”:5

Dickens notes in the preface that he was inspired by two real cases pending for years in the Court of Chancery, one “in which thirty to forty counsel have been known to appear at one time”—probably over the estate of Charles Day—and a second reckoned to be the matter of Jennens v. Jennens, which began in 1798 and would not end until 1915. As life imitates art, Jennens, like Jarndyce, concluded only when the estate had been exhausted from paying legal fees.

The observation was an interesting one given that the Court of Chancery in England was a court of equity.

A brief historical explainer. In contrast to “civil law” jurisdictions, where a magistrate does more to apply a voluminous set of legal codes, usually traceable in parts to the codes of the Eastern Roman Emperor Justinian or Napoleon, to the situation at hand, the common-law courts in England were based on precedent—applying the principles of past cases to new situations. The “common law” evolved not out of a comprehensive setting down of rule statements, but from a long history of judges ruling in particular cases before them. In medieval England, where separation of powers was unknown, the judiciary was simply an arm of the king. In the first centuries following the Norman Conquest, the king would travel with the curia regis—the “king’s court” in Latin—around the country.

The Court of King’s Bench heard legal cases, where the king himself presided. As the curia regis became stationary, fixed at Westminster, and the population grew, cases were heard by justices in the king’s name, continuing a legal fiction that it was still the sovereign dispensing justice. This court was distinguished from the Court of Common Pleas, which heard most routine and local disputes.

Judicial authority split further with a separate body, the Court of Chancery, which heard cases “in equity.” Equity courts had jurisdiction over probate and guardianship cases, among other things, but also often had the power to overrule the courts of common pleas in the interest of fairness. Originally, it was a bishop that held the role as the Keeper of the King’s Conscience and applied equitable doctrines, but then these responsibilities were taken up by the Lord Chancellor, the chief judge of the Court of Chancery.

Of course, these courts were still part of one sovereign—to grossly oversimplify, the king’s justice (common law) was, like its divine counterpart, subject only to the king’s mercy (equity). Chancery was supposed to be less formal and speedier than courts of law, so the interminable Jarndyce v. Jarndyce indicted the court’s failure to live up to that mandate. Early colonial courts, mirroring their English counterparts, often separated courts of law and courts of equity; Delaware’s Court of Chancery, our country’s leading business court, is a vestige of this divide. At the federal level, though, the distinction between law and equity has been abolished: outside of criminal cases, there is but “one form of action—the civil action,” as the second Federal Rule of Civil Procedure says.

Interestingly, the lead expert economist for the government in that trial was Carl Shapiro—who reportedly was the FTC’s economic expert in this Meta case before “parting ways” with the agency back in 2021.

Until recently, Israel worked at Compass Lexecon with Carlton; Israel has since jumped to the upstart consulting firm Econic Partners. Israel shares a reputation with Carlton of being among the best defense-side expert economists. Israel also testified in support of Kroger and Albertsons in the merger proceedings, where the defendants also lost.

Thank you for your insightful, comprehensive, and objective analysis, Brendan.

You brought informed perspective, and provided clever context at every step.

Your updates illustrate in stark detail the vast delta between cookie-cutter legacy media reporting and experienced specialized reporting, separating signal from noise.

Applause for this analysis. Really spectacular. This whole series of articles.

Multi-homing is bullshit. My friends use Facebook and Instagram. It is mostly young people using Snapchat. If Facebook and Instagram are down I cant go to Snapchat as a substitute. I strongly disagreed that multi-homing is common or as simple as the defense proclaimed. Multi-homing bothered me because I felt Judge Boasberg doesnt know if its real or not cause he doesnt use social media. If Meta's apps are down people may go to Youtube and Tiktok but they are not doing the PSN social friend/family communication that happens in Meta's apps. Carlton's argument is all trickery and makes no logical sense. Snap is in the PSN market because it does PSN functions. Youtube and Tiktok do not. When Meta's apps are down I go do something else because Meta has a monopoly on my social and I cant go anywhere else. Youtube and Tiktok are something else. They are not doing PSN. Again, hope Judge Boasberg (or one of his clerks) picks these things up.

Meta controls the sharing between friends/family. They control how many friends/family members see your posts and it pisses everyone off. Thats a clear sign of how strong their monopoly is. They severely limit how many of your friends/family see your posts and instead push reels in your face. Because they have a monopoly people have no choice but to stick around and put up with Meta's using us to compete with Tiktok. Yes that is what is happening. How will Judge Boasberg realize this?

I disagree that Instagram grew faster after Facebook bought it. Instagram was a rocketship. It was at 40m when Facebook bought it and almost 80m when the deal closed. Silly to think Facebook influenced this is any way that mattered. Facebook had nothing to do with Snapchat and it had no problem growing to 500m users. Instagram did not need Facebook. Facebook missed mobile and would be nowhere if it had not bought Instagram. Mark was desperate. He came to mobile with a crappy not-working HTML5 website and not an app. He was toast and we all knew it. Then he bought Instagram to save his tail. It pisses me off to see Meta pretend they helped Instagram rather than saving themselves with this buyout. It just not true.

See:

https://techcrunch.com/2012/09/11/mark-zuckerberg-our-biggest-mistake-with-mobile-was-betting-too-much-on-html5/

I helped get this article written in 2012 months after the announced buyout:

https://www.forbes.com/sites/ericjackson/2012/06/05/why-the-ftc-should-block-facebooks-acquisition-of-instagram/

All of this complex law analysis ultimately rely on the facts and what I worry about for the FTC is whether they knew and argued the facts well enough. I know they left out many things. I think they did a decent job. Lets hope its enough to right this wrong. Facebook never should have been allowed to buy Instagram.

ps. another thing that was never mentioned at trial was how Facebook passed the FTC in the first place. how did they convince the FTC to allow the buyout? the reason is because they pretended Instagram was a feeder app of stylized photos into Facebook when really it was already a 40,000,000 user strong social network competitor. Facebook pretended Instagram was a vertical purchase when it was really a horizontal competitor with 80,000,000 networked users at deal closing. Instagram didnt need Facebook. They could have raised as many billions as they wanted. Instagram owned social on mobile while Facebook was stuck on pc playing around with HTML5. Hope they dont let Facebook re-write the true history.

pss: Instagram founder Systrom went along with all of this because he wanted to be bought out by Facebook. Facebook was the king with the money; they were the first to go public. Systrom wanted to solidify money in his pocket. He told all sorts of fibs to get around the FTC. Only later when Zuck took over Instagram did Systrom get upset because Mark really did want to keep Facebook the king and Instagram under Facebook. Ironically (or perhaps expectedly for some of us) the mobile social network king Instagram is now more valuable than the PC social networking king Facebook. Mark saved himself with a buyout. The FTC allowed it at the time cause they didn't realize it was a horizonal buyout; they didn't know what they were looking at.

See:

https://archive.nytimes.com/bits.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/12/16/disruptions-instagram-testimony-doesnt-add-up-2/

https://www.amazon.com/No-Filter-Inside-Story-Instagram/dp/1982126809

The lesson of all this is that the FTC needs to hire people who understand what all these products actually do if they want to regulate properly.

Cheers!