Lies, Damned Lies, and Statistics: Meta's Case-in-Chief Draws Sharp Words

Our recap of Meta's case-in-chief during Week 6 of trial, featuring its fact witnesses and its warm-up expert economists.

Big Tech on Trial is back. Your author has been tied up in a variety of other legal work for clients, so please forgive my belated write-up from Meta’s abbreviated case-in-chief, which took place at the end of Week 5 and beginning of Week 6 of trial. In the next post, we’ll cover Meta’s main expert economist, Dennis Carlton, and the FTC’s rebuttal from its expert, Scott Hemphill. But in this post, we take a quick tour through Meta’s defense, which featured fact witnesses from Snap, WhatsApp, Walmart, and Instagram, plus two expert economists, John List and Catherine Tucker.

Meta’s Case Begins with Snap

We left off near the end of Week 5, as the FTC had just rested its case. Meta then called its first witness, Saral Jain of Snap. The entire direct was under seal. When court was open again, the FTC was already into cross. There was a rather lengthy colloquy on the admission status of a Snap earnings call, which the FTC said was pre-admitted. Kellogg Hansen’s Ana Nikolic Paul kept objecting that it was hearsay because it contained statements of Snap founder Evan Spiegel, rather than Jain. But as Chief Judge Boasberg pointed out, since the document was in evidence, that was an objection to foundation, not hearsay, so the court instructed the FTC to lay foundation. The objections continued:

MS. PAUL: Objection, Your Honor. He can't speak for Snapchat.

THE COURT: Overruled. He can.

The questions and the objections didn’t go anywhere anyway since the witness answered that he didn’t know the answers to many of the questions being asked, given his role on the infrastructure side of things.

Jain explained how Snap used Google Cloud and then Amazon Web Services in lieu of its own servers, which freed up the company from having to hire as many engineers. This was further down the line from a point we heard earlier in trial, that Instagram didn’t need Facebook’s servers to succeed because it could have just continued using cloud vendors.

On re-direct, Paul pointed out, and Jain agreed, that Snap used to run on the Google App Engine, which could not handle Snap’s growth projections. Snap also eventually concluded that a single cloud provider wasn’t good enough, so de-risked by having multiple providers, which took some time. Much of the re-direct was under seal, too.

Meta’s next witness was also from Snap, David Levenson, senior director of growth. Paul stayed at the podium for the direct. There was a redacted exhibit on consumer satisfaction, the point of which was to show that Facebook and Instagram “were ranked highly in overall satisfaction with smartphone apps.” And users were “more satisfied with the features of Snapchat and Instagram, compared to Twitter and TikTok.”

Next we saw a Snap securities filing, which listed YouTube, Apple, TikTok, Pinterest, and X, in addition to Facebook, Instagram, Threads, and WhatsApp, as competitors, which may help Meta’s case for a broader relevant market. Levenson agreed that Snapchat competed with some of these apps for time and attention, but his answers were careful in explaining that particular features of the apps competed, like short-form video. As “eyeballs and time spent moved from Snapchat or over to TikTok or some of these other short-form competitors, advertising dollars have gone with them,” Levenson said at his deposition. Much of the rest of the direct and cross were under seal.

Meta Moves For Judgment In Its Favor

After Week 5 ended in court, things picked up on the docket as Meta moved for a judgment in its favor under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 52(c). In the motion, Meta argued that the FTC failed to carry its burden on market definition for its proposed “personal social networking services” (PSN) market and failed to show anticompetitive effects. Check out Meta’s motion here:

The court ended up rejecting the motion orally during Week 6, without the need for a detailed response from the FTC. Chief Judge Boasberg said that it would take a “very clear failure” of evidence to grant the motion, so it’s a positive for the FTC that he doesn’t see the evidence that way.

I wouldn’t read too much into the ruling one way or another: defendants often try to get a judgment in their favor at the end of the plaintiff’s case, and courts often reject the move in favor of seeing more evidence. It usually doesn’t make sense to end trial a week early. One famous exception was the directed verdict David Boies and the Cravath team won for IBM at the end of CalComp’s antitrust case against the company in a 1977 jury trial, which was affirmed on appeal.

Trial Continues with Meta’s Expert, John List

After the last of the Snap witnesses left the stand, Week 6 resumed with Meta’s first expert economist, John List, the Kenneth Griffin Distinguished Service Professor of Economics at the University of Chicago. His testimony took up nearly all of Day 21. List is the chief economist at Walmart after turns at the same role at Uber and Lyft; he also served on the Council of Economic Advisers during the George W. Bush administration. List is the pioneer in the use of field experiments in behavioral economics; he’s been shortlisted for the Nobel Prize but hasn’t won. There are more relevant videos out there, but here’s one of List explaining why people are happier when they quit their job:

Meta’s lead lawyer Mark Hansen handled the direct examination of List, which started off with List taking shots at the FTC’s expert economist, Scott Hemphill. According to List, Hemphill’s report “jumps around,” “isn’t an economic analysis that’s serious,” and it includes the app MeWe in the PSN market, which is “economically inconsequential.” List said Hemphill’s analysis “starts as a hypothesis and it ends as a hypothesis.” Tell us how you really feel, professor. List’s assessment was that Hemphill looked at features instead of looking at substitution, while List looked at substitution across his experiments.

List testified about the “attention economy” as a way to think about competition between various apps for users’ time and attention—there’s an opportunity cost to time, as you’re giving up one thing to do something else. There were multiple mentions of List’s principles of economics textbook, a clever way to play defense on admissibility of expert testimony under Federal Rule of Evidence 702 and the related “Daubert test.” Generally, an expert’s methodology is reliable if it’s used the same way in the courtroom as it is in the classroom or field, so tying the testimony back to “textbook” economics is a way to shore up its reliability. Bonus points for pointing to the textbook he wrote.

With that background in mind, List conducted four experiments to assess the FTC’s proposed “personal social networking services” market. The first experiment paid participants $4 for every fewer hour spent on Facebook and Instagram, compared to a control group paid $15-$25 a week to stay in the experiment. (Starting from a pool of some 6,000 participants, the costs would add up; expert reports in monopolization cases can cost millions of dollars.) And the $4/hour incentive to stay off Facebook or Instagram reflected a 12% increase from the average U.S. wage in June 2023 of $33/hour.

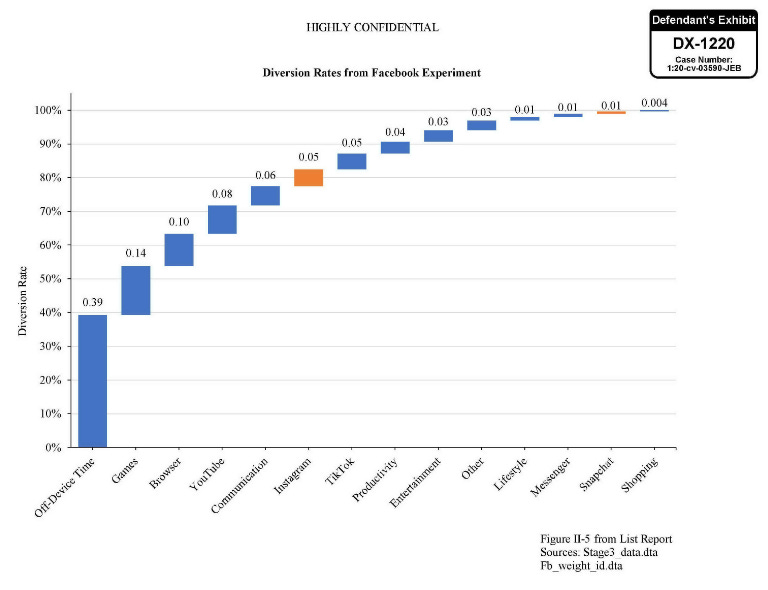

Starting with the participants who were paid to spend less time on Facebook and Instagram, List studied where they spent their time instead. The incentivized group saw Facebook usage decline by 66.6% and Instagram usage by 68.4%. Of time spent on Facebook that shifted to other apps, 9.3% went to Google Chrome, 8.4% to YouTube, 5% to Instagram, and 4.7% to TikTok. The figures were slightly higher when measuring the shift in time spent off Instagram, 18.9% of which went to YouTube, 13.9% to Google Chrome, 12.4% to Facebook and 10.5% to Twitter. Here’s a visualization of the indexed diversion rates from the Facebook part the experiment:

List seemed pretty pleased with himself; he testified that he wants to publish his experiment in a paper when the case is over. List’s point was that more users leave Instagram and Facebook for TikTok and YouTube than for Snapchat, and only Snapchat is within the FTC’s proposed PSN market, suggesting that TikTok and YouTube should be in that market, too.

But Chief Judge Boasberg asked an obvious question: shouldn’t all the diversion ratio percentages in the exhibits add up to 100%? List said that the figures he was rattling off just measured substitution to other apps, but the above demonstrative shows that the plurality of time spent is substitution to something off-device entirely.

On Day 1 of trial, we told you that the antitrust problem known as the “cellophane fallacy”—where price changes are measured from the monopoly price, instead of from the competitive baseline—complicates experiments like this. List said the cellophane fallacy didn’t apply here because the price to use Facebook and Instagram is $0, and because theoretically, in his view, monopolies may improve product quality more than competition. Regardless, Hemphill hadn’t provided an estimated competitive baseline for quality in the PSN market, either.

The FTC objected that this testimony about the cellophane fallacy wasn’t disclosed in List’s expert report, which would mean it can’t come in as evidence. Hansen said that List was responding to Hemphill; Chief Judge Boasberg said that he didn’t think Hemphill had mentioned the cellophane fallacy in relation to List’s experiments, but that he would determine that after trial.

List also brushed aside the “switching costs” that we heard about from Hemphill, which refers to the barriers users face when trying to switch between apps, including, for instance, the inability to magically recreate your same networks on a new or different app. These switching costs were minimal, List said, when considering “multi-homers”—users who have several of the apps installed on their device and have in effect “already paid the switching cost” by creating an account there. The multi-homers switch from Facebook and Instagram to other apps at greater percentages than single-homers do, who may go off-device more instead.

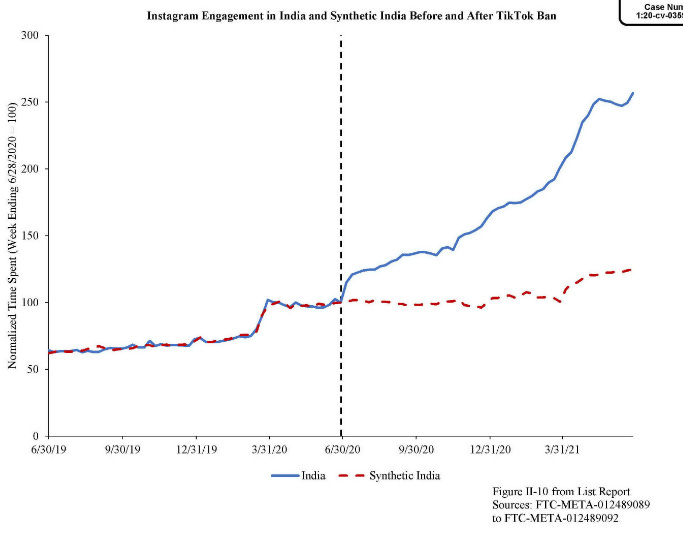

List’s second experiment was what’s called a “natural experiment,” because it’s based on an event that happened in the real world: In 2020, TikTok was banned in India, along with “58 less popular Chinese apps”. The ban resulted in a roughly 20% increase in time spent on Facebook, List said, with gradually more dramatic results for Instagram as users doubled their time as illustrated below:

Hemphill had testified that looking at substitution away from TikTok is not “symmetrical” with looking at substitution away from the proposed candidate market or the monopolist itself. But List said it’s “almost a law in economics that if Instagram is a substitute of TikTok, then TikTok will also be a substitute of Instagram.” While the numbers won’t be the same in both directions, the “sign” (read: unclear if he meant sign or sine) of the relationship will be.

List called his third experiment a “switching analysis” based on a 48,000-person sample from a Meta study panel that tracked app usage. The experiment compared time spent in the first six weeks of the study period to the last six weeks for each person in the study sample. Chief Judge Boasberg was confused, as I was, about what the numbers meant and how they simultaneously were reflecting using an app more and using it less, but the upshot was that between 3.9% and 15.3% of time from Facebook or Instagram shifted to or from TikTok or YouTube.

List’s fourth and final experiment was a “de-merger simulation” that looked at what would happen if Instagram and Facebook were broken up. List called this a “reverse” hypothetical monopolist test (HMT), which is not something I’ve heard of. It sounded like List was trying to come up with some lingo to make his experiment equivalent to Hemphill’s use of the HMT to define the PSN market. (A refresher on the acronyms and other terminology here.) But a “de-merger” that unscrambles the Facebook and Instagram eggs is a much different exercise from imagining what those eggs would look like in a but-for world where they never get cracked because the mergers didn’t happen at all. List’s experiment purported to show that “ad load”—the percentage of impressions on Facebook and Instagram that are ads—would actually increase if the companies were broken up, throwing sand in the gears of the FTC’s argument that Facebook and Instagram are able to control (and increase) the ad load because of Meta’s monopoly power. List predicted a 2.6% increase in ad load on Facebook and 6.9% increase on Instagram after a breakup; a “sensitivity” using different parameters resulted in increases of 2.1% and 4.7%, respectively.

More important than the actual results here was List’s underlying argument that Facebook and Instagram are so-called “two-sided markets.” Broadly speaking, a two-sided market is one in which two sets of agents interact through a platform and the decision of one side of the agents affects the outcomes on the other side, typically in some way other than price. Put another way, in two-sided markets, demand from one side of the market influences demand from the other side. Credit card networks are an example of a two-sided platform, with businesses on one side and cardholders on the other. Advertising is another. The more users there are on Meta’s apps and the more time they spend there, the more valuable Meta’s apps are for advertisers. Thus, the demand on one side (how much users want to be on Meta’s apps) could influence demand on the other side (how much companies want to buy advertising on Meta’s apps).

List criticized Hemphill for ignoring the two-sided nature of Meta’s apps and for focusing on ad load only from the users’ perspective, ignoring the perspective of advertisers. This is important because what may look like a high price on one side might not mean that much when considered with the price on the other side: more ads could reflect a higher quality-adjusted price for users but a lower price for advertisers because the supply of advertising has increased.

The Supreme Court explained in the American Express case, which dealt with two-sidedness, that at least newspapers are an example of a two-sided platform where it may not be necessary to consider both sides because “readers are largely indifferent to the amount of advertising” in a newspaper. Of course, that may not work for the FTC’s theory, which is premised around users being harmed from seeing more ads. List called this a “seesaw” effect: “one side wants to push ad load up, the other side wants to push it down.” Standard economic theory “provides an ambiguous prediction” as to where the seesaw lands, so it’s “an empirical question” for study.

In sum, List was “very confident” that his experiments disproved Hemphill’s opinions because of “convergent validity”: all the results directionally pointed toward the PSN market not being broad enough, so that gives List greater confidence that any one experiment wasn’t flawed.

The FTC’s Mitchell London handled cross. London had been on the FTC’s trial team in the Meta case for a while but recently changed his focus to serve as an adviser to FTC Commissioner Melissa Holyoak; they both stopped by to watch the proceedings earlier in the trial. Perhaps the time away from the case caused rust to build up, as London took his time asking questions. London pointed out that in the diversion studies, when users fled to Google Chrome or left their devices to do something else altogether, both options were more popular than going to TikTok or YouTube. But List didn’t claim that all those other activities, including time not spent on any app, should be part of the relevant antitrust market.

List conceded that the Hypothetical Monopolist Test is a common tool and that he didn’t use it, outside of his “reverse” HMT. There was a back-and-forth about whether List used the concept in his report. The traditional HMT asks whether a hypothetical monopolist could profitably impose a SSNIP: a small but significant and non-transitory increase in price. An app being banned and becoming unavailable is like an “infinite” price increase, by contrast; List agreed. As we’ve explained, an “infinite” price increase would tend to make more distant substitutes look like substitutes that constrain the hypothetical monopolist in a relevant market, which has the effect of wrongly making the market too broad. London also made the point that the 12% subsidy in the second experiment was higher than in a traditional SSNIP, which typically uses a price increase of 5% or 10%. That, too, would tend to make the market too big.

In response to questioning about two-sidedness, List said that Hemphill “predicted that ad load should be 114% and 89%”—presumably referring to figures for Facebook and Instagram, although it wasn’t clear to me which was which. Of course, “that means you need to have more ads than you have impressions,” which is impossible and showed that Hemphill needed to look at both sides of Meta’s apps together. Chief Judge Boasberg at one point said he wasn’t following the math, and overruled an objection because the testimony wouldn’t matter much to him anyway. Asked about some things he didn’t do, List got spicy and said he also didn’t “cite Adam Smith” or John Nash (the latter played by Russell Crowe in the film, A Beautiful Mind).

Meta’s Expert Catherine Tucker

The Google Play Store litigation has been on my mind as another expert from that case appeared in this one: Catherine Tucker, who served as Google’s expert on market definition in that prior case (which Google lost at trial against Epic Games), and testified here as one of Meta’s economist experts, mostly to talk about advertising.

I’ll freely admit my bias from having worked for years to oppose her in the other case. She’s a respected economist but has increasingly become a defense-side expert. Tucker is also representing Meta in helping to decertify an antitrust class action brought by app users, work that the consulting shop, Analysis Group, lauded. On the stand in the FTC’s case, her testimony came across as canned, too cute by half with her British accent and performative gestures. Meta has complained a lot throughout trial about Hemphill’s potential bias in favor of the FTC, but no one gave Tucker a hard time for her pre-existing bias against breaking up Big Tech companies.

The “consequences for [consumer] welfare would definitely be negative” from breaking up Big Tech, she claims below, citing lost synergies:

Tucker has a PhD in economics from Stanford, and she’s now the Sloan Distinguished Professor of Management and a Professor of Marketing at MIT Sloan, the business school. She’s testified before Congress and the FTC.

Tucker had four main opinions: (1) that the FTC didn’t account for advertisers when looking at Meta’s apps; (2) that advertising success is driven by innovation, not targeting users for friends and family sharing; (3) that ad load does not show market power because Hemphill ignores the user experience of advertising; and (4) that Instagram and WhatsApp benefitted from Meta’s support in ways that were critical to their successful monetization.

On the first point, Tucker said that Hemphill “appears to completely ignore” that companies purchasing ads on Facebook and Instagram are constantly measuring their return on investment by looking at how users are responding to ads. There is thus a natural “competitive constraint” in the form of the advertisers themselves. The implication was that advertisers would simply buy fewer ads if people hated seeing them and didn’t interact with them, so there’s a built-in basis for making sure ad load doesn’t exceed what a consumer could bear. If the ads weren’t working, firms wouldn’t be paying for them.

As for Meta’s innovations, it has helped show relevant ads to users, built deployment tools for small businesses to place ad buys without the use of a middleman advertising agency, and brought along engaging ad formats. As an example of a good ad, Tucker took one from her own Instagram feed from Jet Blue, announcing a new nonstop flight from Boston to Madrid. "Sounds lovely,” Tucker said. “It’s relevant because the previous route, there was only one airline, the legacy carrier from Spain on this route.” This was a funny example because the new nonstop flight was announced after JetBlue abandoned its merger with Spirit Airlines, which it only did after the Department of Justice won an injunction blocking the deal in early 2024.

Citing advertising literature, Tucker called ad formats on Meta “both beautiful and engaging,” as an ad for a Newport, Rhode Island-based yacht flashed onscreen. I had thought that de gustibus non est disputandum (“in matters of taste, there is no dispute”), but Tucker pushed her vision of the true, the good, and the beautiful. Chief Judge Boasberg didn’t seem all that interested in her first day of waxing poetic about ads. The more relevant point was that the sailing ad was from a small business that could, thanks to Meta, make an accessible yet eye-catching video, when video advertising used to require buying airtime on a TV network and hiring an expensive ad agency to produce and shoot a spot.

On cross, we learned that a lot of Tucker’s opinions were based on you gotta figure, rather than actual econometrics. It’s “only possible to raise ad load if you’re enhancing user experience,” Tucker claimed before admitting that she “didn’t calibrate it”—i.e., didn’t test if that was actually true. The FTC pointed to evidence about users avoiding ads—doesn’t that tell us something about how they feel about ads? Tucker countered by pointing to the European Union, where users have the option of subscribing to an ad-free version of Facebook; few seem to be willing to pay for that privilege. Left unmentioned was that the European Commission found that this setup violates Europe’s Digital Markets Act. All in all, Tucker’s testimony was more of an interesting FYI than something that had the standalone ability to knock out the FTC’s case.

Meta’s Fact Witnesses Start With WhatsApp

Before calling on its lead economist, Dennis Carlton, Meta’s case next had three fact witnesses: Brian Acton, the co-founder of WhatsApp; Sylvia Yam of Walmart; and Meta’s Nicholas Shortway, who worked on Instagram.

Meta’s wunderkind lawyer at Kellogg Hansen, Leslie Pope, returned for Acton’s direct. Pushing back on Hemphill’s claim that Meta’s apps see a boost in usage during holidays, Acton testified that you might see whatever is “the opposite of a spike” depending on the holiday, giving the example of May Day in Europe, when usage dips. Acton also clarified details that had heretofore been fuzzy around WhatsApp’s subscription plans: in 2014, iOS users could pay $1 to buy the WhatsApp app from the App Store, while Android users subscribed on a freemium model that charged nothing for year 1 and $1/year after that.

Acton also claimed that WhatsApp was “cash flow positive” in 2014, contrary to testimony from the FTC’s expert Jihoon Rim that WhatsApp was losing more than $120 million a year in 2014. Later in the direct examination and again on cross, Chief Judge Boasberg asked about that inconsistency. Acton explained that Rim was looking at net profits using “GAAP accounting” (Generally Accepted Accounting Principles), while Acton was looking at “cash accounting.” GAAP involves amortizing—spreading out—the cost of R&D over multiple years. If you thought of the R&D to build WhatsApp as a sunk cost, then WhatsApp had achieved “break-even profitability,” spending $8 million and “raising” $8 million. Acton said WhatsApp had the opportunity to broaden the subscription model beyond seven countries and knew that, by year 10, WhatsApp could charge $5-$10 annually because it would have “establish[ed] pricing power.” The FTC’s lead lawyer Dan Matheson looked unhappy at the point about the distinction between GAAP accounting and cash accounting.

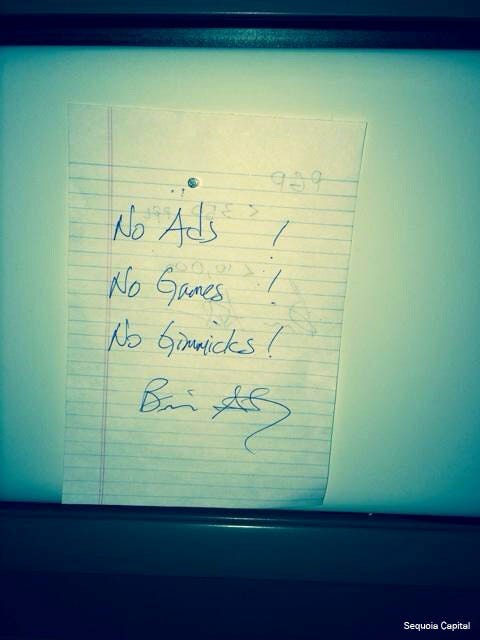

Acton said some other things that scored points for Meta. The United States was not a core market for WhatsApp, and Acton might have called marketing the app in the U.S. like “flushing money down the toilet.” We saw the famous note that read: “No Ads! No Games! No Gimmicks!”

Acton testified that those were features WhatsApp was not interested in building. He confirmed that WhatsApp followed the “Craigslist model” of only doing one thing, deliberately avoiding a path like the China-based WeChat with its “gimmicky features like, ‘meet singles nearby.’” If Meta had not acquired WhatsApp, it still would not have pivoted to building social networking features like a feed and would “absolutely not” have replaced a subscription model with ads. Because WhatsApp was “cash flow positive in seven countries,” but was still rolling out the subscription model, it would have remained independent and not added ads.

Acton also cleared up a final mystery, which was to what extent WhatsApp’s founders had a controlling stake in the company vs. investors who might have later insisted on ads, like Sequoia or DST. Acton said he and co-founder Jan Koum held the “controlling interest” in WhatsApp, so no one could have forced them to offer advertising.

Pope also walked Acton through the merely days-long deal negotiation process that led Meta to buy WhatsApp. Acton said that Tencent, Microsoft, and Google never made formal offers to buy WhatsApp in this period. After the deal closed, Acton and Koum continued to run WhatsApp. Meta didn’t do anything to “hamper” WhatsApp’s growth, Acton agreed, and in fact, Meta helped WhatsApp along with hiring and the use of shared corporate administration like human resources. Using Meta’s “content delivery network” helped “reduce latency,” and using Meta’s storage system was “more reliable and more scalable.” WhatsApp eventually abandoned the subscription model following a “healthy spirited discussion” in Mark Zuckerberg’s office, where Zuckerberg favored “forego[ing] the revenue of the fee in favor of accelerated growth.” Acton disagreed but ultimately “committed to what [Zuckerberg] suggested.” In October 2017, Acton stopped running WhatsApp and then left Meta to help launch the Signal Foundation and the Signal messenger app. Pope blazed through direct; it was hard keeping up with her.

The FTC’s Noel Miller returned to the podium to cross-examine Acton. Around the time of the acquisition, Sequoia had just obtained a seat on WhatsApp’s board of directors for its partner, Jim Goetz. Picking up on the pricing power point, Miller asked Acton if WhatsApp benefitted from network effects and lock-in, and Acton agreed. Miller also highlighted how WhatsApp actually began as something more like a social networking app as it was “just a status application” where users could share what they doing; it only later pivoted to becoming a messaging app. Miller then asked some questions to differentiate “over-the-top” (OTT) apps from standard text messaging. The “over-the-top” part refers to transmission through the internet on top of a phone connection, rather than being sent through carrier protocols like SMS. Acton also agreed that group messaging and a feed are “apples and oranges,” helping the FTC put messaging outside its proposed PSN market. And there aren’t WhatsApp features that help you find friends if you don’t already have their cell phone number, unlike on Facebook.

Miller also tried to cast some doubt on the idea that Meta helped WhatsApp scale, showing an email from Acton stating his concerns that “as we adopt more FB infra[structure] . . . we’re going to have more of these incidents. The more incidents, the more user impact :(“. Pope had tried to pull the sting of this point on direct, when Acton explained that the long-term move to use Meta’s infrastructure was the right one, although it caused some short-term hiccups. And Pope returned to the point on re-direct, getting Acton to say that the storage infrastructure move was “ultimately” a win “even if there were problems.” But Miller established that Acton had such strong disagreements with Zuckerberg and former COO Sheryl Sandberg that he left Meta with $800 million in restricted stock units on the table before they had fully vested—which would be worth about $4 billion today. How much do you have to dislike Sheryl Sandberg to pay $4 billion not to see her?

A Detour to Walmart

Meta’s next witness was Sylvia Yam, who is the Group Director and Head of Strategy for something called “Walmart Connect,” which is Walmart’s advertising service that it offers to suppliers who sell things in Walmart stores or online at Walmart.com. The direct was handled by Aaseesh Polavarapu of Kellogg Hansen, a lawyer a few years my junior that overlapped with me at our prior firm, Cravath.

Walmart Connect places ads on Meta’s apps, as well as on TikTok and Pinterest. Yam agreed that Meta has a “leading platform for ads” that is sophisticated and widely adopted. One Walmart Connect presentation flagged that Meta “faces significant headwinds”—which could mean competition, but the point didn’t land. The FTC kept objecting to questions about the deck as leading, and Chief Judge Boasberg kept overruling them, instructing Polavarapu to “just ask what it says” on the slide without quoting the document. Yam agreed that Meta competes with other apps for user engagement, including time spent. The FTC established that time spent was just one measure of user engagement on cross. All in all, this examination didn’t move the needle much either way.

Meta’s Final Live Fact Witness

Finally, we came to Nicholas Shortway, Meta’s final fact witness called live. He was the second infrastructure engineer hired at Instagram and its 16th employee overall. The point of this examination was to show how much better Instagram became after joining Meta.

When Shortway joined Instagram, “[e]verything was on fire.” There were outages, slowdowns, databases falling out, and problems “on a regular basis,” which were “[d]rastically affecting the user experience.” Shortway carried a laptop with him everywhere he went, and once had to leave his Christmas dinner table to fix Instagram again. Sometimes posts, likes, and comments wouldn’t go through. Instagram had few developers and engineers and was missing “a large number of skillsets to sustain this user and content growth.” They had no one “who knew spam fighting,” and “no one who had a lot of experience in security and privacy” or “content moderation.” Instagram didn’t just go out and hire more engineers because it would take time to find and interview the right people. Shortway hoped the acquisition would help solve these problems; the “running joke was that we were four years behind” Facebook so could learn from what Facebook dealt with already.

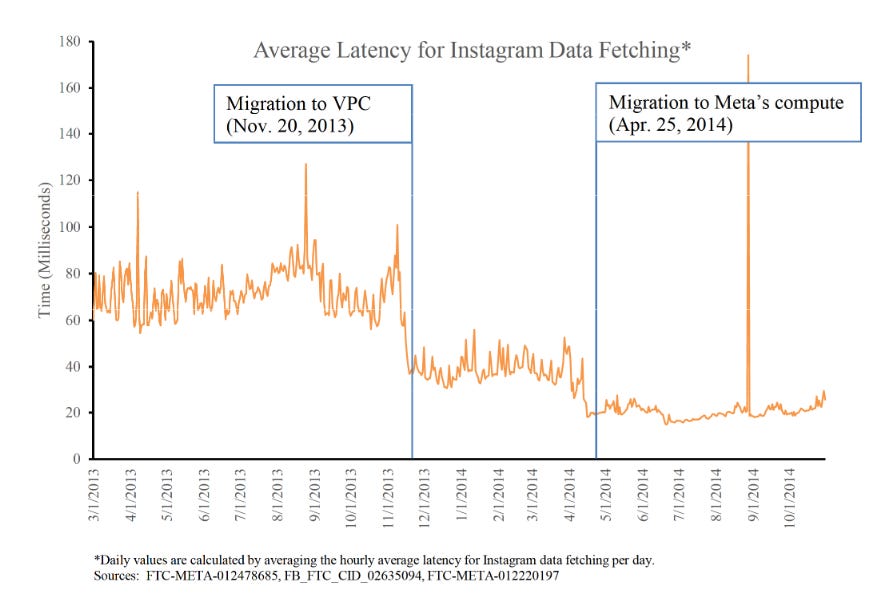

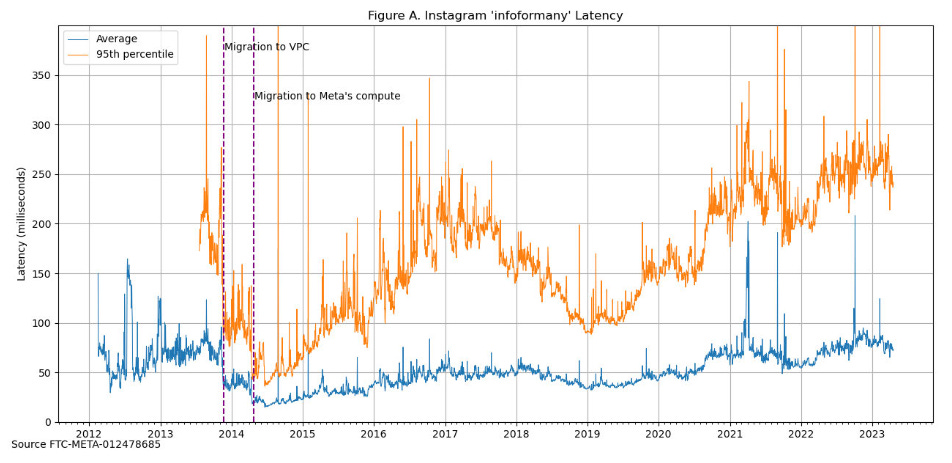

Post-acquisition, Instagram used Facebook’s large team of engineers and recruiters to staff up. The “Instagration”—the internal term for Instagram moving to Facebook’s hardware infrastructure—went “pretty smoothly.” As a result, “all” of Instagram’s metrics “got much better,” Shortway said. After migrating to Facebook’s systems, latency on Instagram improved:

There was a kerfuffle over the admissibility of this chart into evidence, as it seems to have been prepared by a Meta expert witness we didn’t see. Chief Judge Boasberg stepped in to ask Shortway if he personally pulled and verified the data, and Shortway said he did. With that, the exhibit came into evidence. On cross, though, Shortway admitted that the first event flagged here—the migration to “VPC” (Virtual Private Cloud)—happened on Amazon Web Services (AWS), not through any use of Facebook infrastructure. It also came out on cross that Shortway pulled this latency data through April 2023, but the chart ends eight-and-a-half years before that. The FTC did one better and then showed the full data:

Oh look, latency has in fact gotten worse on Instagram in the near-decade after the endpoint on Meta’s exhibit. Shortway protested that things didn’t get to pre-acquisition level of bad until “maybe 2023,” and that this reflects “10 to 25 times” more data than the 2014 period, on account of the growth in Instagram users and richer content like video.

On cross, the FTC also did a good job poking at the foundation or knowledge Shortway had for his statements. He actually didn’t join Instagram until a month after Facebook/Meta had already acquired it! Shortway said that the issues he was talking about continued in the early post-acquisition period, and he was basing his statements about the pre-acquisition Instagram on conversations with co-founder Mike Krieger. The FTC also pointed out that Instagram had access to the cutting-edge features of AWS, which hosted the app before the Instagration. At one point, Instagram needed more storage from AWS, and AWS delivered that less than an hour later. But Shortway disputed that AWS could handle Instagram; even after moving to VPC, “we still were fighting fires every single night due to the same exact problems that we had before.”

Cross started to drag on with lots of detail about different hardware issues and metrics, so after an objection from Meta’s lawyer, Chief Judge Boasberg prodded the FTC to be more concise. The upshot of the line of questions was that, as late as 2018, Instagram was “outpacing its allocated capacity on Meta’s infrastructure,” at least temporarily. Shortway called this a “champagne problem,” which he didn’t fully explain. Here’s what Chief Judge Boasberg said he took from this cross, which “wasn’t going anywhere”:

THE COURT: Of course, they wouldn't be affected by ones that they're not on, but if they were on the other, they would be affected by those.

In other words, by being on Meta’s infrastructure, Instagram faced some unique problems that it wouldn’t have faced if Instagram kept using AWS. But as Shortway kept saying, Instagram would have faced different problems on AWS. So the FTC’s turn with Shortway on the nitty gritty of servers didn’t amount to much.

At that point, Meta’s lead lawyer, Mark Hansen, made his angriest objection of trial to date, accusing the FTC’s attorney questioning Shortway, Barrett Anderson, of making a misrepresentation to the Court about the parties’ agreement to disclose trial exhibits four days before testimony. “I don’t know if this gentleman wasn’t informed about this case. He hasn’t appeared in the case before. It is an outright misrepresentation to the Court” about the Court’s order, Hansen said. After figuring out that the issue was about disclosure of exhibits intended to be admitted through cross, Chief Judge Boasberg simply said that “we have fulfilled our utility in this discussion” and would be “proceeding on,” without resolving the objection. It was another moment of credibility lost for Meta by being overly aggressive about something that truly does not matter in the grand scheme of things. The things admitted through cross were emails and data from Meta. The objections from both Meta and the FTC during this examination were mostly incorrect and a waste of time.

On re-direct, Meta showed Shortway an email of AWS being unable to meet Instagram’s demands. While Instagram had lowered its target for acceptable outages to 8 hours a year, that’s still a fraction of all the time in a year for an app with billions of users, Shortway explained. He summed up AWS as trying “everything they could do to help us out, but they themselves didn't have the capacity that we needed.”

Meta also offered some video depositions that the press and public haven’t seen. We’re still chasing those down, but we’ll bring you the final battle of the experts in the last wrap-up post from trial, along with some of the FTC’s video depositions.

Stray Thoughts

We don’t tend to think that our coverage has all that much influence on trial, but List said some things to suggest that he read this blog: accusing Hemphill of saying the “sky’s blue but it’s really red,” harkening back to our language on Day 11. And List kept using “bowling” as an example of something else an app user could spend their time on; we covered the connection between how Mark Zuckerberg describes Facebook and the Robert Putnam book Bowling Alone before trial.

One point of evidence. When Miller showed Acton his email, the chain had statements from other people on it. Miller said Acton’s email fit within a hearsay exception as a statement of a party opponent. Technically, a party opponent admission is not an “exception” to hearsay; under Federal Rule of Evidence 802, it’s not hearsay at all!

Correction: An earlier draft misspelled the last name of the WhatsApp co-founder. It is Jan Koum, not Youm.

Thank you! And bonus points for using the word "kerfluffle".

watched you speak live today:

https://itif.org/events/2025/06/26/ftc-v-meta-takeways-from-a-landmark-trial/

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8npn89G1ies

https://ibb.co/4n86f93Y

we know the complete slant and spins of ITIF. so many misstatements of facts by ITIF. these people are against all antitrust law and enforcement. I struggled to listen to these debaters.

this case is not about time and attention

Facebook/Instagram have total control of PSN to the point they can and do limit Friends/Family sharing; the numbers on sharing are controlled by Meta. This is harm. I want more people in my network to see my posts and Facebook and Instagram will not allow that. They limit our sharing with Friends/Family because they want us to watch videos so they can compete with Tiktok.

Instagram had 80m+ users before Facebook closed its purchase. Instagram was growing so fast Facebook freaked out. Instagram did not need Facebook for anything. It was Mark Zuckerberg and Facebook that was desperate to acquire Instagram. Facebook needed to Instagram as Facebook had nothing working on mobile phones. Facebook had an HTML5 website for Facebook and not a native app.

Tiktok is not Facebook or Instagram. My friends/family don't make content on Tiktok. They share nothing on Tiktok. These debaters people dont appear to understand the difference between the apps because they don't use them.

I am hoping the FTC wins and feel they should based on law and the facts.

Thank you