What Was WhatsApp Worth?

A flurry of expert and third-party witnesses on Days 7 and 8 of FTC v. Meta Platforms reveals details about WhatsApp's valuation and insights into TikTok, Discord, and Reddit.

This weekend edition of Big Tech on Trial incorporates the exhibits posted Friday night in FTC v. Meta Platforms, first used on Day 7 of trial (Wednesday, April 23). The second week of the FTC’s trial to break up Meta finished off with expert witnesses and third-party witnesses from TikTok, Discord, and Reddit on Days 7 and 8. As we’ll get to below, the testimony was often repetitive and drew incisive questions from the presiding judge.

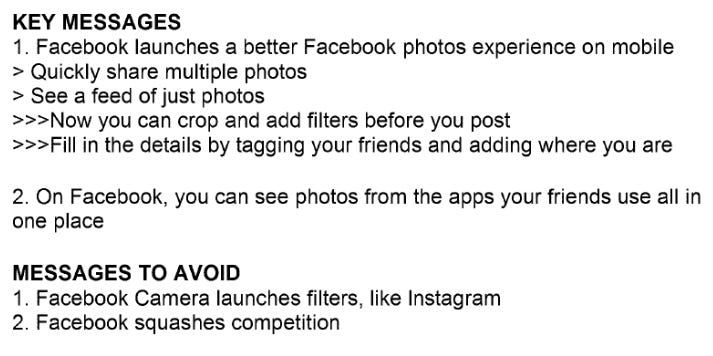

But first, the second week of trial touched on Facebook Camera, a short-lived would-be competitor to Instagram. Dirk Stoop, a former product manager for Facebook Camera, was the FTC’s first witness on Day 7.

Message to Avoid: “Facebook Squashes Competition”

Camera was Facebook’s home-grown answer to Instagram and its first move to offer a standalone mobile photo sharing app, code-named “Snap.” In early 2012, Mark Zuckerberg had what’s called a “Zuck Review” with Stoop, whose notes mention that getting Camera “out the door fast is a huge priority” because “Instagram is growing quickly.” An internal Facebook “Competitor Analysis” of Instagram in early April 2012—shortly before Facebook’s deal to buy Instagram was announced—called Facebook’s mobile app, then available only on iPhones, “really not far ahead on Mobile”.

Camera ended up launching, for iPhones only, in May 2012, about six weeks after the Instagram buyout was announced. A set of talking points around the public messaging for the release of Camera sought to avoid comparisons to Instagram and the suggestion that “Facebook squashes competition”:

Stoop, for his part, thought that Camera added something unique: the ability to post multiple photos at the same time. Consistent with Zuckerberg’s Facebook post announcing the deal, Stoop also saw Instagram as distinct because users could follow accounts from people they didn’t know. “I saw Instagram as a place for creative photography,” he said. “That’s not necessarily how people were using Facebook or Camera.”

Echoing Sheryl Sandberg’s testimony that Camera had not been shut down right away after the Instagram acquisition, Stoop explained that his team grew over time and, in a retrospective email, called the goal of the app to make “mobile photo sharing on FB substantially better and incorporate what worked well into the main iOS and Android apps.” Camera continued for at least two more years, with about “280K-ish folks” using the app “month over month” despite “no marketing efforts and very few updates.”

I Love Lampe

Day 7 continued with another FTC expert witness, Cliff Lampe, a professor at the University of Michigan who previously made an appearance at the FTC’s pre-trial tech tutorial. Lampe is a resident in the School of Information, where he researches human-computer interaction and the “social and technical” structures of online communities.

Lampe is not an economist, but his testimony about the design of social networks and social norms around them was meant to buttress the FTC’s personal social networking services (“PSN”) market definition. He viewed PSNs as those apps that “enable mass personal, low-cost maintenance of relationships with broad networks of real-life personal connections.” Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat met that definition, but TikTok, YouTube, Reddit, iMessage, and LinkedIn did not. In evaluating whether an app is a PSN or not, professor Lampe considered: (1) the use of someone’s real name vs. pseudonyms; (2) mutual or unilateral connections between users; (3) whether content is by default shared with friends or posted publicly; (4) personal sharing v. sharing around interests, work, or the neighborhood; and (5) active participation v. passive consumption. On these dimensions, he looked at norms in addition to the design and rules of the app.

In thinking about the importance of norms, I couldn’t help but remember the “LinkedIn, Facebook, Instagram, Tinder” meme Dolly Parton started just before the pandemic in 2020, before others imitated it:

What makes the meme both relatable and relevant to the current trial is the recognition that we highlight different things about ourselves on different social media platforms. In the Facebook version of themselves, Kerry Washington and Mark Hamill are surrounded by family, part of what the FTC calls the PSN’s core use case of friends and family sharing. But in the LinkedIn versions, our subjects are suited up, as if for a job interview. The Instagram photos seem more produced or artsy. And the Tinder shots target, well, a much different use case.

But by Meta’s logic, these photos should all be the same. For example, it sees Facebook and Instagram competing with LinkedIn, YouTube, and TikTok, in part because all these apps have a short-form video feature. But norms go beyond the design to show how consumers use the apps in practice. The meme makes it clear that most users instinctively appreciate that different platforms are used for different things.

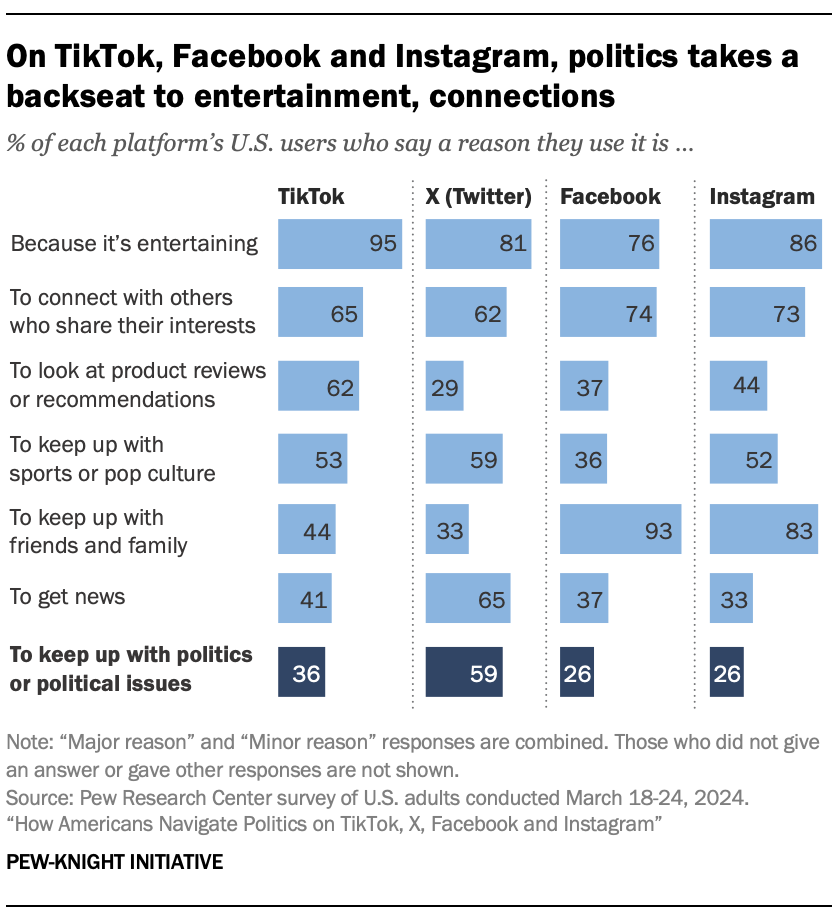

Professor Lampe’s focus on norms, though, wasn’t something quantifiable. On cross, Meta’s lawyer Daniel Dorris of Kellogg Hansen had Lampe admit that he did not attempt to quantify, for example, the prevalence of pseudonyms on social media sites. On cross, Lampe looked at his own TikTok profile, which uses his real name, and Dorris pointed out that a number of Lampe’s followers appeared to be people Lampe is close to. On direct, Lampe had referred to exhibits containing Meta’s own descriptions, like sign-up pages for Facebook touting the site as a place “to connect with friends, family and people you know”; but on cross, Dorris showed similar-sounding statements from TikTok, including its friends tab. Lampe also looked at some national surveys like one from the Pew Center:

On direct, Lampe noted a finding from the Pew Research Center (above) that “fully 93% of Facebook users say keeping up with friends and family is a reason why they use the site, including 75% who say this is a major factor.” The figures were high for Instagram, too: 83% and 54%, respectively. But on cross, Dorris showed that Lampe neglected to mention that 44% of TikTok users said they used TikTok to “keep up with friends and family.”

Chief Judge Boasberg summed up the dispute on market definition about the potential competitors Meta faces and the use cases for those other apps as a battle between a difference in kind (the FTC’s view) and a difference in degree (Meta’s view). “Why isn’t it just a difference of degree?” he asked. Lampe said that he did not speak to the degree of difference between apps as part of his analysis. But he did find a “strong difference in how people are motivated” to use different platforms.

Chief Judge Boasberg also asked, “How likely are norms to change?,” pointing to shifting norms around phone calls and voicemails, where text messages have become much more popular. “Aren’t norms changing all the time?” Lampe answered that those norms did not change overnight, and that it was hard to say they were driven by technology. (I wouldn’t read too much either way into Chief Judge Boasberg’s questions; they were phrased suggesting agreement with the defense, but that may also have been a way to simply give Lampe an opportunity to respond directly to the defense’s points.)

Lampe also offered a thought about how total time spent on Meta’s apps is increasingly spent on video: “The nature of video is that it is longer to watch. A movie takes two hours.” But it takes far less time to read a Facebook status or check in with a loved one. Just because the video use case takes more total time doesn’t make the friends and family function less important.

While Dorris tried to impeach Lampe a number of times with his deposition testimony, for me the most effective part of the cross cast doubt on Lampe’s methodology. Earlier, I wrote that the FTC’s first expert, Rim, also amounted to little more than an expert gloss on the evidence that was already making its way into the record. That’s the impression I was left with after Dorris finished with Lampe. Maybe Lampe’s five-factored methodology makes sense in theory. But in its application and execution, it’s unclear how much to weigh his opinion about pseudonymity if there was no attempt to quantify a proportion of pseudonymous handles or ask users about that. Pressed with each omission, Lampe simply responded that he looked at each app “holistically.” It felt like a vibes-based application of the methodology. And that’s usually something that judges will view with skepticism.

Meta’s 135% Overpay for WhatsApp

Day 8 began with another FTC expert witness, Kevin Hearle, a staff financial analyst who investigates claimed efficiencies from proposed mergers. As Chief Judge Boasberg asked later on it, “Isn’t the point or theory that [the WhatsApp buy] was a vast overpay, because [if] it didn’t make sense economically, it was to squash competition. That’s the ultimate point of the analysis, right?”

Hearle wouldn’t go that far. It wasn’t his assignment to opine on whether it was an overpay. His task was simply to evaluate whether Meta paid a “transaction premium” to acquire WhatsApp above its valuation and if so, by how much. Comparing the $19 billion acquisition price to an $8.1 billion valuation of WhatsApp by accounting firm KPMG, Hearle identified a transaction premium of $10.9 billion, a 135% premium over the actual value of WhatsApp before the acquisition.

Chief Judge Boasberg questioned Hearle’s use of the KPMG number when Hearle provided a range of valuations on a demonstrative slide with a bottom-line valuation of $12.5 billion, which would have implied a lower overpayment. Hearle replied that while he did the overpayment analysis using both valuation figures, the $12.5 billion “came from an internal Meta email that described that value as including some premium,” so Hearle only included it in his report as a “lower bound” or “maximum valuation.” It didn’t sound convincing, as the slide appeared to show the $12.5 billion last, as if it were Hearle’s best or final estimate. Hearle also showed that the $19 billion WhatsApp purchase price represented 11% of Meta’s $173.5 billion market capitalization at the time.

The court also asked why Hearle dismissed purported synergies from the WhatsApp deal. Hearle said there was no documentation on that and, tellingly, Meta did not highlight any in its presentation to the board of directors to recommend buying WhatsApp. Chief Judge Boasberg asked about Meta’s plans to monetize WhatsApp in the future by targeting small businesses: “Why should we be looking at where we’re frozen now if Meta’s position is [that] the real value is around the corner?” Hearle said that while he wasn’t asked to analyze WhatsApp’s post-acquisition profitability, he did compare projected WhatsApp revenue to actual WhatsApp revenue, finding a “wide gap between hoped-for, targeted” revenues and “actuals.”

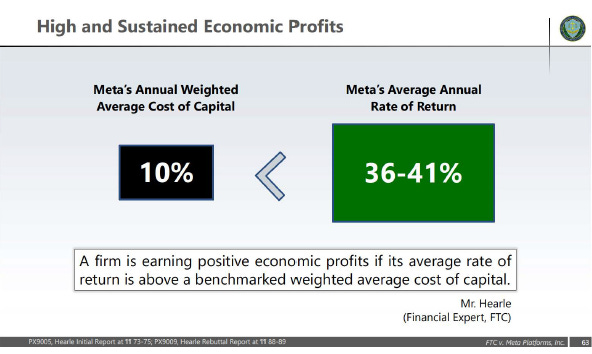

Hearle also offered a more general opinion on Meta’s economic profits, which the FTC will use as evidence of Meta’s monopoly power. Hearle compared Meta’s profits to its weighted average cost of capital. Because its average rate of return exceeds its cost of capital, the FTC’s economist Scott Hemphill will likely argue that Meta is a monopolist:

On cross, Meta tried to show that Hearle didn’t have an opinion on Meta’s purported long-term plan for WhatsApp, which is only coming into view more than a decade after the acquisition, while the data Hearle had analyzed ended in 2022. Hearle reiterated on cross that Meta did not undertake a traditional valuation in its presentation to the board of directors, instead trying to estimate the revenue per user it would need to generate by dividing the purchase price of $19 billion by the number of active users. Other valuations compared WhatsApp to Google, where WhatsApp’s revenue per user was 10 cents and Google’s was $30—300 hundred times greater. Hearle rejected some other proposed valuations for not looking at the value of WhatsApp as a standalone entity. And on economic profits, Hearle didn’t use an industry benchmark to compare against Meta’s average annual rate of return.

TikTok Take Two

The FTC ended the first week of trial on a high note with video deposition testimony from former interim head of TikTok and COO V. Pappas. On Day 8, we saw deposition testimony from another TikTok executive, Blake Chandlee, then the President of Global Business Solutions and formerly in a business role at Facebook. Chandlee’s responsibilities focused on monetizing TikTok by selling advertising. Consistent with Pappas, Chandlee explained that TikTok “doesn’t rely on relationships between friends and family” but on interests, so is “very different” from Facebook and Instagram, which are social platforms.

Chandlee said that when he first met Mark Zuckerberg, Zuckerberg “explained the concept of a social graph and these edges and nodes that exist between people” with an “underlying value proposition [that] my friends and family are the kinds of content that I want to see in these environments.” TikTok, as Chandlee described in a 2022 CNBC interview, is “an entertainment platform. . . . The difference is significant. It’s a massive difference.” Chandlee agreed that users “check” Facebook and Instagram but “watch” TikTok because videos take longer to watch, and users may watch 10-50 clips at a time.

Getting at market definition and monopoly power, the FTC asked Chandlee if TikTok could vary ad load, the proportion of ads users see relative to other content, by user. TikTok did not do this. In the U.S., rough ad load on TikTok is between 10 and 12 percent, Chandlee testified. On the other hand, he agreed that TikTok competes “on a number of levels with a variety of different platforms and mediums,” including television, radio, the outdoors, and digital players, both “in terms of users’ time and attention as well as advertising spend.” TikTok competes with television networks, Twitter, Instagram, Amazon, and Snapchat specifically, he said, where the biggest ad budgets are allocated.

Game On: Discord and Reddit

Next on Day 8 was a live examination of former Discord executive Julia Tang over Zoom. She was “Vice President, consumer business go to market.” She explained at a high level, with screenshots, how Discord servers work. A server built around the video game, Minecraft, for example, was broken down into a variety of interest-based subchannels for text, image, and voice chat. Simultaneity of communication was important to Discord, which focused on cutting down latency, the time it takes for a message to show up on a user’s computer.

While the FTC seemed to be setting up Discord as a specific use-case built around gaming, Tang surprisingly answered that the primary use for the app is to communicate with friends. While gaming was and is a core use case, the pandemic saw a shift to more all-purpose communication with friends. She answered elsewhere, though, that Discord wasn’t built around a social graph because the focus was on “people’s shared interests as opposed to individual peoples’ connections.” Discord does have a 1:1 messaging feature as well, like Facebook and Instagram do, and Tang would pay attention to Meta’s apps even if they didn’t do exactly what Discord offers.

Closing out Day 8 (and the second week of trial) was a deposition video of Winter Raymond of Reddit, an in-house counsel who oversees product, ads, and privacy. Raymond likewise showed how Reddit works, where users post on threads in forums predominantly using pseudonyms because “users come to Reddit to be anonymous.” User profiles feature the account’s creation date—the “Cake Day,” in Reddit parlance—but seldom an actual photo or identifying personal information, unlike on Facebook and Instagram.

Indeed, users don’t need to give any personal characteristic information to Reddit, or even an email address, to create a Reddit account. One Reddit document said the site competed “for people’s time and for global advertising spend” with a variety of products for entertainment, including TikTok, Facebook, YouTube, Snapchat, Roblox, Twitch, and Instagram, as well as with publishers like the New York Times and Vox Media.

On recess before the last clips were shown, Chief Judge Boasberg called the deposition video a “[t]ough way to end a day. Tough way to end a week I should say. Here we go again.” The testimony has been repetitive so far, but it’s cumulatively pointing one way: lots of apps compete for time and attention from users and placement buys from advertisers. But the apps have different functions and different norms.

We’ll be back from the courthouse for Week 3.

Other Things

I ran into FTC Commissioner Melissa Holyoak in the hall outside the courtroom with her staff on Day 8. She had come to observe the trial. That’s a sign of how seriously FTC leadership is taking this case. In her prior role as Utah’s Solicitor General, Holyoak led the case against Google’s Play Store business practices and hired me and my colleagues to serve as Special Assistant Attorneys General for Utah in that matter. Tom Barrabi of the New York Post has reported on Holyoak’s time spent working outside of Washington, but this was the third time I’ve seen her in town myself in the past couple of months. She spoke at the law firm WilmerHale in February, and we had lunch a few weeks ago near the Y Combinator Little Tech Competition Summit.

This is such bullshit I cant believe it is not 100% clear yet.

Youtube, Tiktok, Reddit, Linkedin, are not the same as Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat.

Any 12 year old knows that.

The only reason Facebook isnt being laughed out of the court is because the Judge is older and doesn't use any of these apps.

These apps are truly completely different.

Following friends on Tiktok? NO! Not the same as friends on Instagram. Please.

Is it possible to follow something of friends on Tiktok? Sure. a tiny bit maybe but thats not following friends on Facebook and Instragram.

They need to make this much more clear with data and not let the defense lawyers play with words.

A funny comment about the discord competing with Facebook comment. My wife's family does in fact use discord as a replacement for Facebook / Instagram. Its structured entirely differently and though we come looking for the same content we would look for on Facebook, our ability to get it is much lower, and our ability to distribute it as much lower. We use it because our ability to block out unwanted stuff, such as ads but also privacy issues, is much higher. Old Facebook let me check on old friends. Discord just lets me keep in contact with a small group that all know each other.

My family, by contrast has moved to group me. It has many of the same limitations if not more. Once again, it allows me to keep in touch with a specific group who all know each other or at least all have a common identity

Both products are inferior to Facebook, or rather to what Facebook promised to be back when we used it. That Facebook is now gone, and no one has been able to come up with a true replacement after Instagram. At least not one that I'm aware of.