Day One: The FTC Calls Its First Witness, Mark Zuckerberg

The FTC wastes no time getting to the heart of its case to break up Meta after radically different opening statements.

The E. Barrett Prettyman courthouse in Washington, home to the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia, has seen its fair share of merger trials over the years. But monopolization cases have been the rarer bird. United States v. Microsoft, tried in 1998, adorns an exhibit in the courthouse’s gallery. And United States v. Google, tried in 2023, will resume a week from today down the hall from my assignment, FTC v. Meta Platforms.

Both of those prior cases loomed large in the opening statements from Daniel Matheson, the FTC’s lead lawyer, and Mark Hansen of Kellogg Hansen, Meta’s counsel of choice. The FTC framed the case around two simple questions from the court’s summary judgment opinion: Was Facebook a monopolist? And were Instagram and WhatsApp actual or potential competitors when Facebook acquired them? Meta, for its part, sought to poke holes in the evidence, and to offer procompetitive effects and resulting efficiencies from its buyouts.

It was a contrast between the competition that was(n’t) and the competition the FTC says should have been.

If you read our preview, you know the broad strokes. By way of brief review, the FTC’s opening statement argued that Meta is a monopolist in a “Personal Social Networking Services” market (the “PSN market”). Within that market are “friends and family” apps like Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat, and privacy-focused MeWe. Outside of that market are platforms like LinkedIn (for professional updates), TikTok (short-form video content), Nextdoor (for neighbors) and Twitter (oft-pseudonymous news alerts).

Regardless, the FTC says that it need not define a market anyway, since there is direct evidence that Meta is a monopolist—it’s able to raise “quality-adjusted prices” through increased “ad load,” command high profit margins, discriminate based on price, and exclude rivals. The FTC, following the court’s lead at summary judgment, made its case exceedingly simple: Instagram and WhatsApp were legitimate threats to Facebook’s monopoly power in personal social networking, and that’s why it acquired them. And if that’s not enough, the FTC previewed evidence of additional harm to consumers: more ads (specifically, the variable rate of ads shown as a percentage of all content—”ad load”), worse privacy, and reduced incentives to innovate lest Meta’s apps cannibalize each other’s users.

Of course, Meta’s opening saw things differently. It’s hard to dispute that Meta’s Hansen gave the more confident, crisper, and more charismatic opening. And on a surface level, it resounded with common sense. There wasn’t direct evidence of monopoly power since Meta doesn’t charge users any price, output is increasing, and even Meta’s share of research and development as a percentage of revenue is increasing and far surpasses comparable Big Tech companies, he said. What is more, Meta argued, the FTC never benchmarked a competitive level of price, output, or quality against which to judge purported price increases or quality decreases.

As for “ad load”—so what? "If you don't like an ad, you scroll past it. It takes about a second," Hansen said. Laughter followed in the press room. And Meta innovated targeted ads, which some users do find value in. After all, they click them and buy things.

Meta gored the FTC’s proposed PSN market as “gerrymandered,” pointing out in side-by-side slides how you can watch videos, share recipes, send messages, and shop on apps within and without that market—using nearly identical screenshots to illustrate the point that iMessage, TikTok, YouTube, and other platforms compete with WhatsApp, Instagram, and Facebook. Implicitly taking issue with the court’s summary judgment ruling, Meta cited Microsoft for the proposition that the voluminous intent evidence (in the form of contemporaneous statements from Meta executives) must take a backseat to the actual competitive effects.

Teeing up its argument that the acquisitions of Instagram and WhatsApp were in fact beneficial, Meta previewed expert economist testimony that the acquisitions generated between $38.5 and $110 billion annually in “efficiencies.” Not exactly a precise range. The FTC was quick to throw cold water on it, citing caselaw. In terms of style, it was the persistent and earnest Matheson, pens in pocket, against the pithy and bravura performance from Hansen.

There’s just one problem for Meta—a lot of its arguments sound good but don’t make economic sense.

All Wrapped In Cellophane

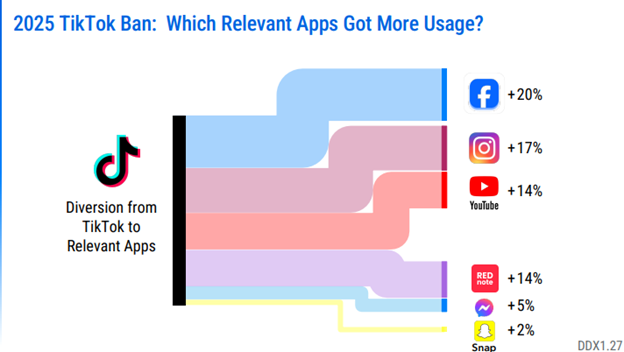

As previewed last week, Meta’s opening statement made much of the fact that users switch between apps in response to “shocks” or “natural experiments” that take a subset of apps offline. One recent dataset came from the fleeting moment earlier this year when TikTok was briefly offline as a result of the Protecting Americans from Foreign Adversary Controlled Applications Act (aka the TikTok “ban”). Meta threw up a slide showing how platform usage shifted to Facebook and Instagram, evidence that it says demonstrates that TikTok competes with Meta’s apps in the same market:

And there were other experiments previewed too: a natural experiment—a 6-hour outage of Meta apps in 2021—and “field studies” by Meta expert economist John List of the University of Chicago, which purport to show diversion from Facebook and Instagram to YouTube and TikTok when users received small monetary incentives to go off-platform.

Meta’s talking points persuaded some reporters that TikTok in fact competes with Facebook and Instagram, negating the FTC’s preferred, narrower PSN market. And that would be great for Meta by lowering its market share—as measured as a percentage of time spent on apps—to below 60%, it says. (We can bracket for now a debate about whether 65% market share or something less, with high “entry barriers,” is enough to show monopoly power.)

But there are two major problems with these experiments. First, the natural experiments involved the total loss of apps rather than a small but significant change to price or quality from the competitive level. One way economists define markets, which courts accept, is to find the smallest set of products for which a monopolist would find it profitable to raise prices above or diminish quality below a competitive level by a small but significant amount (generally called a “SSNIP test” when addressing changes in price, which can be modified to address quality and choice, where price is not as easily measured.) The 2023 Merger Guidelines—which FTC Chair Ferguson recently reaffirmed—say as much: we might look at “how customers have shifted purchases in the past in response to relative changes in price or other terms and conditions” (§ 4.2.A (emphasis added))—not absolute foreclosure of the app, which by its very nature will tend to overstate the substitution to other apps that matters for defining a relevant market.

The second problem is what’s known as the “cellophane fallacy,” which takes its name from an antitrust problem where DuPont—the single manufacturer of cellophane wrap—conducted a SSNIP test using its prevailing monopoly prices, instead of from a competitive benchmark, which brought in aluminum foil as a substitute and made the market too broad. Data showing substitution away from Meta’s apps in the actual world may simply reflect that Meta is a monopolist that has degraded the quality of its products so much below the competitive level that more distant substitutes—TikTok and YouTube—look like real substitutes. And although Meta claims that the FTC didn’t benchmark a competitive price or quality level, doing so was likely foreclosed because Meta has been a monopolist in the FTC’s market for the last 14 years.

The bottom line task is to find the smallest relevant market for assessing competition, not the largest one. Put another way, Meta’s argument boils down to the idea that all apps compete against each other in that they compete for consumers’ finite time or attention. But by the FTC’s measure, that’s a market without a limiting principle.

There’s an old joke about how anything can be a double-edged sword: “football is fun, but then something else is too and you’re not watching that.” Does that mean that football and every other form of entertainment should be considered together in one big recreational marketplace? No. And Meta does not compete against every other app solely because we have but one life to live.

If this is all a lot to take in right now, that’s understandable. Both parties will be teasing out how competition happens over the course of this trial.

The News Feed Is Expanding to Meet the Needs of the Expanding News Feed

The other point that Meta’s opening and superstar witness, Mark Zuckerberg, kept coming back to was that Meta users are spending less and less time on the core “use-case” for the FTC’s proposed market—friends and family sharing. Add to that an inelegant statement from the FTC’s expert economist Scott Hemphill that everything on Meta’s apps should be lumped into the PSN bucket, and Meta’s counterargument writes itself: TikTok competes with Meta’s video feeds, eBay with Facebook marketplace, and so on:

Meta sought to show that users today spend less and less time sharing with friends and family:

Instead, consumption of videos, of content from non-mutual connections, or even from unconnected accounts, now makes up most of the activity on Meta’s apps. From Meta’s standpoint, this means that Facebook is no longer what Mark Zuckerberg said it was more than a decade ago. Friends and family connections are still important, but that’s just one purpose among many, from watching videos to playing games to selling couches.

The FTC’s opening sought to preempt this line of argument with some legal maneuvering; once a firm is outside the relevant market, it doesn’t matter if some of its products or features compete with some of the products or features of a firm inside the market. The Google Search liability ruling provides a good illustration. Although specialized search functions competed in some respects with more generalized search, that ultimately didn’t matter—specialized commercial search vendors were outside the market precisely because they didn’t have a general search product for commercial and non-commercial use.

But there’s another reason that Meta’s point is too cute by half: Meta can’t use the very evidence of “enshittification” of its products—of anticompetitive effects from degrading them—as evidence that a market for those products does not exist or is way broader than the FTC’s.

In other words, Meta shouldn’t be able to say that friends and family sharing isn’t the key use case simply because its algorithm is shoving more and more unconnected and commercial content down users’ feeds against their will. That is a kind of Soviet way of thinking about market definition: We can’t have restrained the output of bread, you see, because there is so little bread now that most people eat grass, therefore there is only a market for grass. To repeat it is to refute it.

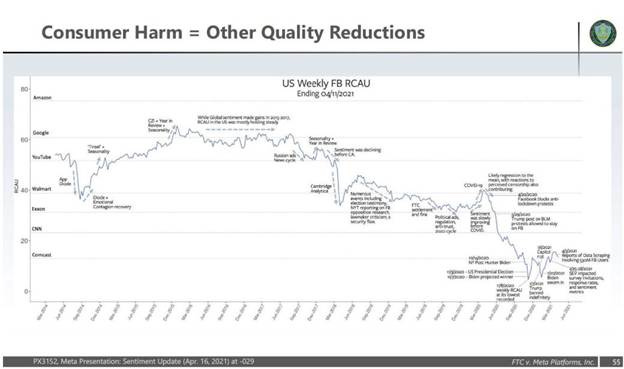

And some of the FTC’s highlighted evidence refutes it too, as consumer sentiment for Meta’s products has fallen off a cliff since 2017, even compared to platforms that Meta says it competes with, like YouTube:

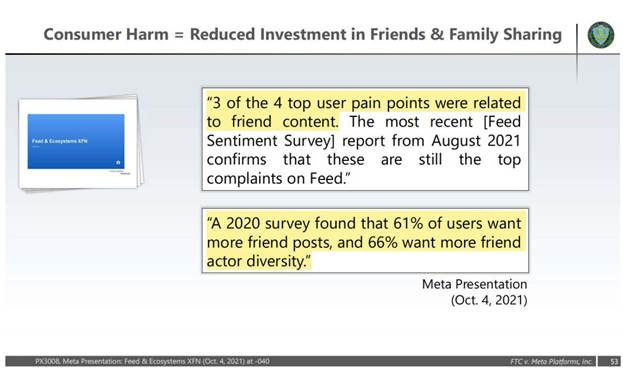

Early 2010s emails from Zuckerberg and a consumer survey as recent as 2021 cited in the FTC’s opening showed that Facebook users consistently wanted to see more friends and family content:

But what they got instead is a platform that, by Meta’s admission, delivers less and less. That strikes me more like the absence of competition than evidence of competition.

“The FTC Calls Mark Zuckerberg”

Matheson wasted no time. Everybody agrees that the FTC’s case leans heavily on Zuckerberg’s own communications. So it was a bold move to start the trial with the star witness, rather than build up to the moment.

I didn’t think early questioning of Zuckerberg was all that effective. The Facebook founder seemed reasonable, thoughtful, and, as his emails show, articulate about economics in a way that allows him to modulate his answers to help his case. At the start, Matheson didn’t seem to have much “control”—an admission from the witness’s deposition using the same words as the lawyer’s question. You need “control” because smart witnesses tend to always be closing and throw up hurdles to the answer you’re looking for, even if their testimony is literally true. So, one after another, up went early Zuckerberg communications about friends and family sharing, and Zuck did his best to restate that use-case as one among many.

But after a couple of these exhibits, something started to change. Zuckerberg became less believable.

Instead of just showing Zuckerberg the exhibit and asking questions about what he wrote, Matheson started asking Zuckerberg questions using the language from his prior statements. After Zuckerberg demurred in a long answer, out came the statement—or in one case, out came a long video about the difference between web-based and app-based Facebook. Then, Zuckerberg would try the spin zone again.

By the time the FTC marked an exhibit showing a Facebook signup screen to “connect with friends” and family, Zuckerberg’s repeated statements that that was just one among many uses—and not the core strategy—seemed canned. And Zuckerberg’s emails kept getting better, as the FTC took the court through the threat Instagram posed to Facebook:

"If Instagram continues to kick ass on mobile or if Google buys them, then over the next few years they could easily add pieces of their service that copy what we're doing now. . . . I view this as a big strategic risk for us if we don't completely own the photos space."

The best exhibits that we’ve seen at summary judgment and in the opening statement are still to come, along with the WhatsApp story.

Trial will resume tomorrow with a continuation of the FTC’s examination of Zuckerberg. Because witnesses will only be called once, expect Meta’s direct of Zuckerberg to immediately follow the portion that is the FTC’s case-in-chief.

Stray Observations

For your reference, here are the opening statement slide decks: from the FTC and from Meta.

Bigwigs at the trial: FTC Chair Andrew Ferguson was there, along with Meta’s chief legal officer and many defense-side lawyers. Hanging out on the Meta side was conservative appellate superlawyer Paul Clement, who’s been busy lately writing an amicus brief in the Eric Adams criminal case and challenging the executive order targeting WilmerHale. Clement and Mark Hansen, Meta’s lead trial lawyer, teamed up a few years ago in a Burford Capital-backed suit by bondholders against Argentina, winning one of the largest U.S. judgments ever: $16.1 billion.

Tech issues and technicalities have been a recurring problem for the FTC’s trial team. At the tech tutorial last week, it took some time to get their slide show on the courtroom screens. Today, lead FTC lawyer Dan Matheson was tripped up by exhibits that he thought were preadmitted or shared with the other side but weren’t. To Chief Judge Boasberg’s chagrin, the FTC several times published exhibits before moving them into evidence or stating that they had been preadmitted, contrary to the court’s instructions. Chalk it up to nerves and needing to triple check the exhibit list. But these things can eat away at credibility with the court. And they take the wind out of what should be high courtroom drama—the scheduled 7-hour grilling of the defendant’s CEO. Mark exhibits, then authenticate/lay foundation, then move to admit them, then publish to the courtroom, then ask your questions. They’ll get there, but they’re not in easy rhythm yet.

Exhibits are filed here two days after examinations. We’ve been able to preview some here that were in the opening statements. We’ll update future pieces as exhibits hit the docket.

It's clear that all of these companies, not just Facebook work for the same people behind the scenes.

They all went along with censoring those who questioned 911, COVID, Ukraine war, Gaza genocide, etc.

Also notice how these tech "geniuses" are always ones that stole or bought in.

-Zuckerberg stole and bought out

-Bezos bought out

-Bill Gates stole and took the credit for what his partner did

-Musk bought in and took credit for Tesla

Geniuses my a$$.

https://posthumousstyle.substack.com/p/are-the-tech-bros-insane

https://robc137.substack.com/p/left-brain-vs-whole-brain-in-battlestar

Wouldn't it be interesting to hear from Instagram founders on what they envisioned when they assumed Zuckerberg would live up to the promise to give them independence and control over Instagram.