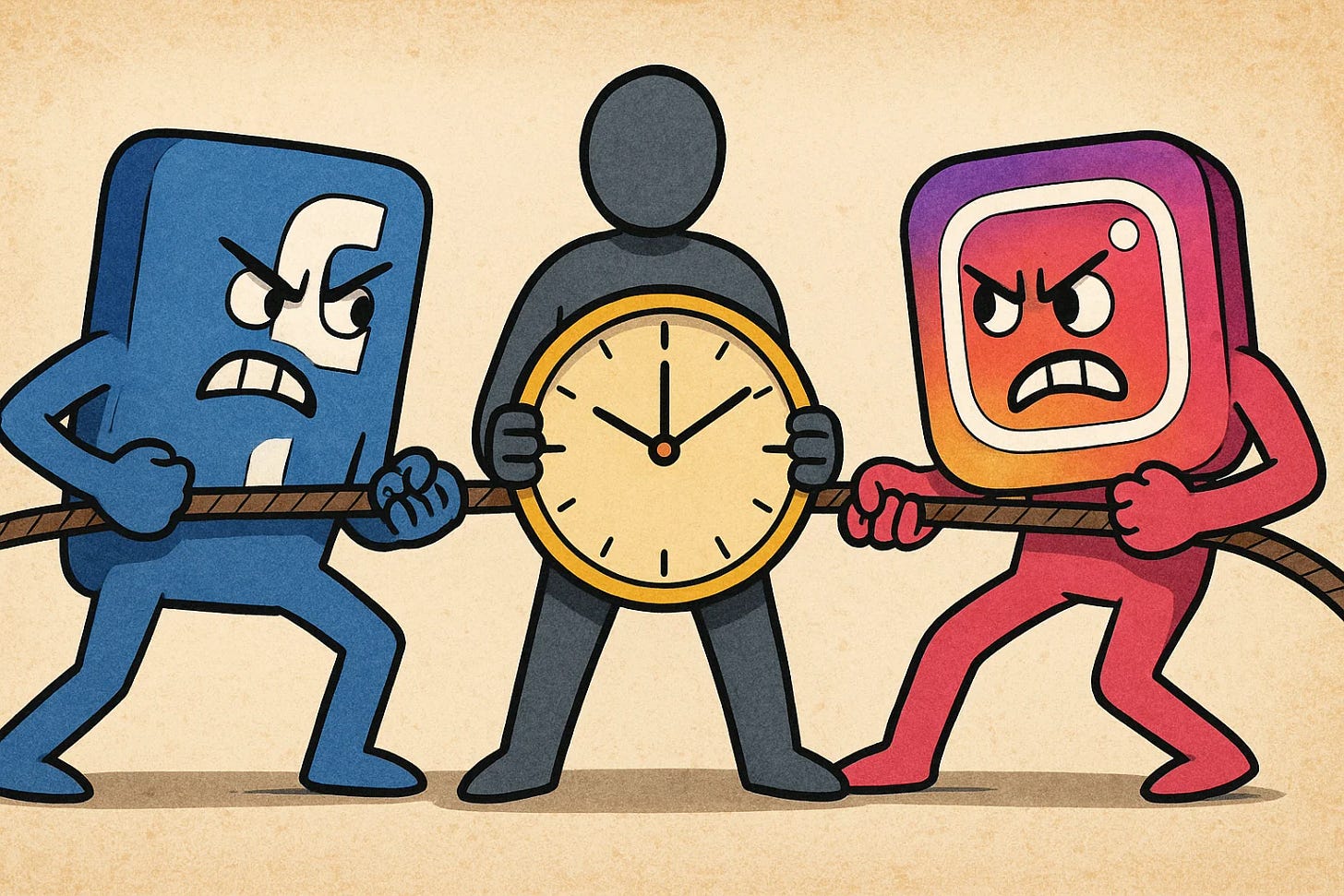

"A Lot of Emotion": The Rocky Marriage of Instagram and Facebook

With Instagram co-founder Kevin Systrom on the stand, the sixth day of the FTC v. Meta trial was the government's strongest yet.

Big Tech on Trial reported last week on Mark Zuckerberg’s tendency to monologue on the witness stand. But one line of questioning stood out as touching a potential third rail: a module from Meta’s lead lawyer Mark Hansen that attempted to preempt what would be damaging testimony a week later. “How did Instagram’s founders react to organizational challenges?” he asked the Facebook founder. “Not super great,” Zuckerberg said. In the CEO’s telling, Facebook had supported Instagram but didn’t “give them every single thing they wanted.” There were disagreements with decisions to pull back on some marketing for Instagram.

“What’s the bottom line on their tenure?” Hansen asked about Instagram co-founders Kevin Systrom and Mike Krieger. Zuckerberg answered: “I’m very positive on both of them.” There “aren’t many people who can” build such a good product. Zuckerberg paused, searching for the words. He “found them to be very . . . they . . . had good values” and were “focused on creating value for our community.” He paused again and added, “Everyone has their quirks.”

We heard the other side of that story during the second week of the FTC’s trial to break up Meta. Instagram co-founder Kevin Systrom testified for nearly all of Day 6 (yesterday, April 22). The FTC has started to land its punches at trial, but Day 6 was without a doubt the high point of its case so far. Systrom speaks well, with good recall of events. He answers questions carefully and puts his prior statements in context without coming across as disingenuous. He is unflappable and frequently flummoxed Meta’s lawyer with laconic answers over the course of cross-examination. And his testimony cast serious doubt on Zuckerberg’s claims that Facebook was supporting Instagram post-acquisition.

All in all, Systrom was an ideal fact witness for the FTC.

Early Days

Instagram started as an app called Burbn. Akin to Foursquare, Burbn let users check in at bars and restaurants, make plans to meet up, and post pictures. Systrom and Krieger discovered that users were spending most of their time on the app’s photo-sharing feature. Retooling the app to focus solely on that, they named it Instagram.

Instagram’s growth was explosive. At the time Facebook (now Meta) announced its acquisition of Instagram, the latter app had 30 million users, solely from being available on Apple devices. Around the time the deal closed in August 2012, that had grown to 100 million users. The Instagram team had 13 employees at the time; 6 were engineers. From Meta’s perspective, that growth in users is partially attributable to simply being associated with the Facebook brand, but there was another, likelier catalyst: Instagram became available on Android in April 2012.

From about one month into the app’s existence, Instagram used Amazon Web Services (“AWS”) to host the data for its app to work, rather than make large capital outlays to buy and build their own servers. Systrom said Instagram used AWS “well into” its time as part of Facebook. AWS was “sufficient,” and Instagram “rarely had any problems with AWS.” There were also “significant” costs to moving Instagram over from AWS to Facebook’s servers. That eventually happened, but piecemeal, over time.

Systrom’s testimony responded to claims by Zuckerberg and Meta that Instagram needed Facebook’s servers and “infrastructure” to gain scale. But what Systrom showed was that Instagram had scaled to 100 million users without any Facebook infrastructure and then, post-acquisition, didn’t fully use that infrastructure for some time. Instagram “did not do the deal just to get servers,” he said.

Instagram was also succeeding in getting funding to meet the increased demand and cover the higher costs from greater AWS usage. Systrom detailed a seed round, a Series A round, and a Series B round of funding. In 2012, Instagram’s Series B included investment from Greylock Partners, Sequoia Capital, Thrive Capital, Benchmark, and some others for $50 million total, valuing the startup at $500 million, as we heard from Roelof Botha of Sequoia the other day, whose video deposition wrapped up before Systrom was called. Botha wanted Sequoia to have a bigger slice of the pie, but there were too many “pigs at the trough,” he said.

The FTC’s examination also highlighted that there were other potential buyers for Instagram. Systrom recounted a sushi dinner shortly before the Series B funding round with Twitter’s then-CEO (probably Dick Costolo) and Benchmark partner Peter Fenton where the tech wizards traded war stories about their companies. Instagram let Twitter know they weren’t interested in talking more after that and wanted to stay independent.

Systrom also recalled informal meetings with Google in their corporate development office—where he once worked before starting Instagram. And Apple met with Instagram four or five times, too, sending the head of their photo product team and a product marketing manager. Sean Parker, who was involved in Facebook’s rise, told Systrom he had been “prodding various Facebook folks including Zuck” to buy Instagram “quickly and at any cost”—although these statements were hearsay and inadmissible for their truth.

The FTC also had Systrom distinguish Instagram from other apps that Meta might argue were part of the same antitrust product market, like Flickr and Treehouse. On that score, we saw an email from Kevin Systrom explaining that Instagram was “not a photo sharing site”: “It’s a way of communicating what I’m up to, where I am, who I’m with, etc. Photos just happen to be the medium through which that happens.”

Systrom of a Down

When the deal closed and Instagram became part of Facebook in August 2012, there was a “tremendous amount of excitement and talk about promoting Instagram.” But the honeymoon was short-lived. In October, Systrom emailed Javier Olivan, now Meta’s COO, who was then overseeing “growth” for all of Facebook, about delayed promotions for Instagram. “I’m concerned that it sounds like we’re getting stuck in analysis paralysis—instead of being entrepreneurial and moving forward with some low hanging fruit that is pretty obvious it’ll help the growth of this property (IG) within Fb,” Systrom wrote. As a trial tactics aside, the FTC seemed to be hewing close to the documents to get Systrom to “parrot” what they said, as Chief Judge Boasberg put it at one point. It probably would have been more natural to just ask him questions and show him the emails if he couldn’t remember or said something wildly different.

Even before the deal formally closed, Twitter had cut off “find your friends” access for Instagram. A version of contact sharing, the integration allowed Instagram users to find their Twitter connections’ accounts on Instagram. The report from Twitter’s VP of business development was that this was “in direct retaliation [for] [F]acebook cutting off the same API access to Twitter.”

By June 2014, Facebook staffers working on “growth” for Instagram were told to stop working on Instagram. Systrom “recall[ed] loving those people” but “woke up one day and they were gone.” The Instagram team didn’t have “an antagonistic relationship” with them before they were yanked.

The difference in staffing levels was stark. Systrom noted that when Instagram had 1 billion users, that was about 40% of Facebook’s reach. But Facebook had 35,000 employees, while Instagram’s dedicated team totaled around 1,000.

Systrom gave another example: “Mark would make a proclamation that video is the future” and then ask different teams how many additional employees—called “headcount”—they needed to deliver on video. In a 2017 instance, Meta made 300 employees available for video company-wide; Instagram received none of them. Systrom complained by email: “We were given zero of 300 incremental video heads which is an unacceptable and offensive outcome.”

Things went similarly during the company-wide push for “integrity” in the wake of the Cambridge Analytica scandal; Instagram again got zero new employees, and its total “integrity” team came in under 20 staffers. Instagram’s “comments” feature was similarly “starving” for attention from engineers, and Systrom flagged singer Demi Lovato deactivating her account “because of comments,” and then “defecting to Snapchat,” as he put it.

Why did this matter? Wasn’t everyone part of one company? Systrom explained, “[U]nless you have people working on your team directly, very little tends to get done, [you’re] at the whims of other people’s priorities and we simply weren’t one at the time.”

More personal dynamics were also at play. Systrom testified that his experience with Zuckerberg was that “he was happy to have [Instagram] in the family” but that as the founder of Facebook, he “felt a lot of emotion around which one was better, Instagram or Facebook.” There was a “logical and emotional tension”—logic favored supporting Instagram to grow the combined company’s bottom line and Zuckerberg’s wealth, while pride might suggest that Facebook had to win arm wrestling contests for scarce resources against its sibling app.

Things came to a head in 2018, and Systrom would leave by September of that year. We saw previously that Zuckerberg was looking at shifting more ads from Facebook to Instagram to achieve some kind of equilibrium across the apps. Systrom consistently pushed back on increasing ads to Instagram over time. For a while post-acquisition, he personally reviewed every single ad shown on Instagram. In 2015, he wrote that the combined company “[s]hould be sensitive to the fact that there’s a community of 371m people out there that have basically never seen an ad on Instagram.”

Systrom testified that while in theory reaching some kind of equilibrium made sense, in practice, Instagram would need to show a lot more ads than Facebook would to reach an equivalent amount of revenue. Because Facebook’s ad platform was more “mature,” it was more efficient in targeting ads than Instagram was. The level of advertising that Instagram would need to show to reach Facebook’s level of revenue per ad would start to cannibalize ad revenue by causing a drop off in user engagement, time spent, and the number of daily active users.

During the 2018 imbroglio, Systrom made his views clear: “I think this would be a terrible tradeoff.” Zuckerberg had a list drawn up of all the ways Facebook was helping Instagram. Systrom said he was “[t]old toward the end that all of those were being turned off.” For Systrom, Zuckerberg “believed that we were hurting Facebook’s growth.” Systrom left.

Why does it matter whether Zuckerberg and Systrom got along after the “Instagration”? (Instagration: noun: a portmanteau of Instagram and integration used by Meta employees to describe the merger.) The FTC alleges that Meta’s acquisition of Instagram was itself illegal conduct aimed at “neutralizing a competitor.” If the FTC meets its initial burden of showing that the acquisition was anticompetitive, Meta may rebut that by showing that it had a non-pretextual, procompetitive justification for the deal. And Meta’s rebuttal is premised, in significant part, on the fact that Meta helped Instagram flourish, creating value for consumers.

So these facts are not just insider gossip, juicy as they are. If Facebook in fact did not devote many resources to Instagram or if Instagram would have succeeded as a standalone company rivaling Facebook, then Meta’s procompetitive justifications seem pretextual. The FTC succeeded on Day 6 at puncturing several holes in Meta’s professed generosity. The trial record now includes several facts that Facebook actively sought to throttle Instagram’s growth, and that is critical evidence for the factfinder in this case, Chief Judge Boasberg. What is more, the rivalry between Facebook and Instagram even as part of the same company supports the idea that they would have been competitors if they stayed separate.

The “Sir” Heard Round the World

Kevin Huff of Kellogg Hansen did a lengthy cross-examination of Systrom. Like the FTC did, Huff tried to stick closely with documents where Systrom used language that might help Meta’s case. But Huff ran into problems, as it wasn’t clear whether he was impeaching Systrom or trying to refresh his recollection, a point Chief Judge Boasberg asked about several times.

Huff tried to skip the documents by asking questions like, “Isn’t it true that you said xyz in this interview?” But Systrom’s out-of-court statements were inadmissible hearsay, so Chief Judge Boasberg cautioned Huff not to ask questions adopting those statements.

Some highlights from cross:

In this 2023 Vox interview, Systrom said: “People have flocked to services like TikTok or Twitter or Facebook less to connect with their friends . . . and more and more to be entertained.” Asked about it, Systrom called Twitter an entertainment platform that is text-based. And he agreed that Facebook, TikTok, Instagram, and YouTube compete for video consumption.

Meta tried to show that Systrom’s views about how big Instagram was in 2012 were inconsistent with the usage figures given by the FTC’s economist expert, C. Scott Hemphill. Hemphill had estimated 3.9 million monthly active Instagram users in the United States as of March 2012. Systrom said that sounded low because 30 million users were registered around that time, with about 40% as monthly active users, or 12 million, the majority of which were in the United States. Meta refreshed Systrom’s recollection that, in fact, there were only 9 million monthly active users in that period, making 3.9 million seem more appropriate. Systrom said it still sounded too low. This dispute matters because Meta wants to show that Instagram didn’t have many U.S. users when it was acquired. But Hemphill was using third-party Comscore data, rather than Instagram’s own data, for March 2012.

Huff tried to establish that Instagram had lots of problems before Meta bought it. Systrom agreed that he spent most of his time keeping Instagram running (A: “That is the job.”), getting pings to his phone sometimes every 15 minutes that the app was down, which gave Systrom something like “PTSD”. Huff asked if startups run on duct tape. At that point, Chief Judge Boasberg leaned over to joke with Systrom, as if to say: yes, duh.

Huff also showed Systrom some emails around the time of the “Instagration” between him and Zuckerberg. In the email, Systrom credited “fb links”—cross-posting from Instagram to Facebook—for helping Instagram grow: “[T]hey are, after all, what got us to where we are today.” Huff accused Systrom of lying by being complimentary in this email to Zuckerberg, and Systrom answered simply, “Sir.” He said it wasn’t misleading and that these communications were negotiation tactics; Instagram wanted to persuade Facebook that Instagram wouldn’t cannibalize users from the Facebook platform but were instead complementary. In March 2012, for instance, Systrom told Zuckerberg that “most of the photos on Instagram are not social photos”—contrary to what the FTC is trying to show now.

In another interview, this time from 2011, Systrom called Instagram “not a friends network” but an “interest network”—making it sound similar to how the FTC describes TikTok. Huff also found out that Systrom’s dog has an Instagram account, which counters the FTC’s point that Instagram consumers use their real names. Q: Does your dog use her real ID on that account? A: “I’m not sure I understand the question.” We also covered “finstas”—“fake” Instagram accounts, often a second account from an existing user that is nevertheless pseudonymous, the opposite of how the FTC says people use Instagram.

Probably the most effective sequence of the cross got the FTC’s lead lawyer, Dan Matheson, to shake his head. Before the acquisition, Instagram decided “not to compete” with Facebook. Systrom said they never expressed ambitions about becoming a general social network and that he spent less than 1% of his time thinking about Facebook as a competitor.

Other sequences weren’t as successful. Asked whether he had used language in prior testimony, Systrom said, “No.” This is the right way to deal with tough cross questions; fighting them has a Goldilocks effect by calling more attention to the point and potentially hurting the witness’s credibility.

Asked if Instagram could have succeeded or failed if Facebook didn’t acquire it, Systrom said, “Those are the two options.” Joining Facebook was like attaching to a “rocket ship” of success, Systrom said. But the “probability” that Instagram would fail on its own was low, he thought. While Facebook accelerated Instagram’s building out of video features, Systrom was “almost certain [that] we could have built a video product alone.” It was also difficult to imagine what would happen in the but-for world if Instagram never joined Meta because Systrom didn’t “know if Mark would have cut us off or not from things like distribution.”

Ultimately, Systrom concluded that Meta’s integrations between Facebook and Instagram increased Instagram’s growth between 25% and 40% annually.

That covers Day 6, on April 22. We will separately cover the testimony from April 23 in a future post: Dirk Stoop of Meta and Cliff Lampe, one of the FTC’s experts.

Stray Thoughts

As for Zuckerberg, a little-known outlet, Luxurylaunches, reported yesterday that he is “[n]ot just the fittest CEO in Silicon Valley” but “also the most adventurous.” We have been unable to confirm their report that the tech mogul, “wanting to make the best of the Easter holidays, sailed his $300 million superyacht with a helicopter 5,300 miles from San Francisco to Norway so he could go heliskiing on icy fjords”. Zuckerberg’s testimony concluded on Wednesday last week, so the report suggests that he went more or less straight from court to the frosty hinterlands in his Blofeld-style yacht.

Lay off the basketball stuff. We covered how the parties tried to make use of Chief Judge Boasberg’s basketball fandom in their tech tutorials. Kevin Huff lobbed another reference during his cross of Systrom, saying that Steph Curry has a better jump shot than he does. Awkward silence followed in the courtroom. The press room was silent, too, before bursting out in laughter. It’s generally better not to make the trial about yourself as a lawyer, and not making jokes is one of the cardinal rules of that. Meta’s lawyer Alex Parkinson on Monday might have been given some advice in this direction; his second time on cross was notably more muted. Some lawyers can be effective by being snippy and jokey. But the most effective lawyers are the ones who lead the fact finder to doubt a witness’s testimony on their own, simply listening to the witness’s words. A corollary of this rule came from the Bromley-Barr-Boies tree: a Cravath lawyer was to wear “court ties,” which are conservative, dark ties; polka dots were permissible. The idea is not to be flamboyant and draw attention to yourself in court, but to fade into the background so the focus is on the witness and the documents.

Thanks Brendan, great coverage. The more I read about these techies the more I say do away with al of them. Socialize? Go outside, walk, get fresh air and exercise and talk with some real people, not robots on a computer.

But I am old and out of touch. I remember those days. Oh well.

Great stuff Brendan :)