Was Meta Failing at the Job It's Hired For? The FTC Wraps Up Case-in-Chief

As the FTC closed its case, a recurring question emerged: If users "hired" Instagram (and Facebook) to connect with friends and family, was Meta failing them by de-prioritizing that feature?

The FTC’s case-in-chief finished last week, on May 15, and Meta put on its entire case between then and May 21. We’re breaking down our summary into two parts: this entry will round up the last of the FTC’s fact witnesses. The next post will cover Meta’s witnesses.

This is a long post with a lot of detail. But let’s ground this in terms of what’s in dispute: Are Facebook and Instagram social networks that provide, first and foremost, connections with friends and family, and therefore form part of a relevant “personal social networking services” market? Or have they moved away from that core function as they compete for users’ time and attention against other apps? Keep that in mind as you read below.

A bit of housekeeping: we had previewed that the testimony of Alex Schultz, Meta’s Chief Marketing Officer and Vice President of Analytics, had been broken up over multiple days of trial. We didn’t cover him in depth before we got to FTC expert Scott Hemphill last week, so the full summary of his multiple days of testimony comes first.

Then we pick up where we left off with Tom Alison, Head of Facebook. (We’ve now heard from the “Head” of each of the three main Meta apps, including Head of WhatsApp Will Cathcart and Head of Instagram Adam Mosseri. You can read about their testimony here and here.) Rounding out the FTC’s case as its final witness was Bradley Horowitz, formerly of Google.

Meta’s “Fairy Godmother of Analytics”: Alex Schultz

We’ve seen him throughout trial at Meta’s counsel table, and his testimony was broken up over Weeks 4 and 5: Alex Schultz, Meta’s Chief Marketing Officer and Vice President of Analytics. Schultz is the head of analytics for all of Meta. His role seems to touch lots of different aspects of the business, and he was (predictably) a decent witness for Meta. Schultz has a theatrical touch, and he seems like a “company man”—he’s been with Meta since 2007. He’s also smart and willing to give easy answers to uncontroversial questions.

The FTC’s exam of Schultz began with a June 2012 email from him with the subject, “focus.” Schultz sets forth “2 main areas of focus as a team,” growth targets and revenue targets.

According to Schultz, Meta’s key “growth target” was Messaging, where it sought to reach “the next billion users” as a defense against Meta’s “greatest competitive threat”:

And Schultz testified that Facebook was “really worried about small group sharing” and “friends and family sharing going to messaging,” which is “what played out.” Schultz mentioned LINE, a chat app that’s popular in Japan, Thailand, and elsewhere in Asia. The FTC had an exhibit at the ready, where Schultz says that Facebook will beat LINE on “time spent,” but that messaging was a “threat”:

Another exhibit, a “Messenger competitive landscape” deck from 2012, looked more like it supported Meta’s view. There was language about the “tremendous threat” from LINE, Kakao, and WeChat, but the deck didn’t list WhatsApp as having a similar “social” networking feature:

The FTC tried to get Schultz to say that Facebook Messenger was losing to these competitors in terms of overall messages sent, but Schultz pushed back on that. “In the U.S. we were roundly beating them by a large margin,” he said, explaining that a comparison would have to be made country by country.

Questioning turned to Japan, where Facebook wasn’t doing as well, and was losing to Twitter for some period, Schultz said. Between an exhibit and his testimony, Schultz said that Facebook had “dropped the ball on Japan.”

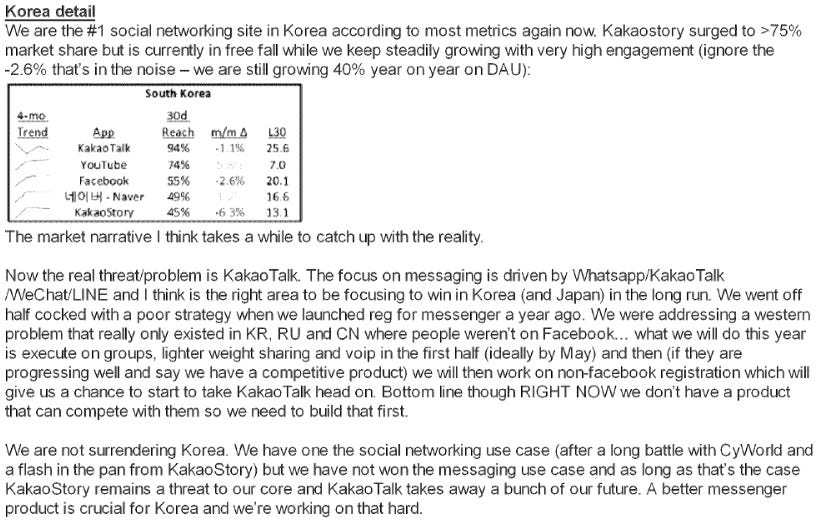

Another exhibit reiterated the threat of messaging apps in Korea, and although WhatsApp was among a handful of apps “driving the focus on messaging,” Schultz nevertheless testified that WhatsApp was in a different category from the other Asia-based messaging apps:

This is about where Schultz’s testimony ended up before he stepped down while Instagram Head Adam Mosseri stepped in for scheduling reasons. When Schultz returned, we saw this email where Schultz offers to pump the Facebook Messenger team up after “the fallout” from the WhatsApp acquisition. The first bullet here is incredible:

Schultz characterized this email as reflecting his view that Facebook could “have a go” at iMessage. He feels like “it’s always up for grabs,” including today. There wasn’t much defense or explanation for the first bullet, which speaks for itself.

Schultz, like Zuckerberg, is familiar with the concept of “network effects”—in short, that a service’s value increases when there are more people on it, and high network effects can be a significant barrier to entry for new competitors. By way of example, Facebook’s value, as the FTC argues, wouldn’t be very high if you didn’t have a whole lot of friends or family connections. Schultz invoked the concept in an internal bid to acquire the messaging and VOIP app, “imo”:

This email also gave Schultz an opportunity to whip out his German pronunciation of StudiVZ, the now-defunct Berlin-based social network mentioned above. Chief Judge Boasberg couldn’t help but smile at the Shecky Schultz routine. We’ve seen many documents that this line of questioning was getting at, but again, Schultz was careful to distinguish between WhatsApp on the one hand and WeChat, LINE, and Kakao on the other.

Why? Well, the FTC’s case against the WhatsApp transaction turns in large part on whether the evidence of competitive concern from the Asian chat apps is good enough to infer that Facebook saw WhatsApp as a threat, which is highly probative evidence that it was a threat, as Chief Judge Boasberg explained at summary judgment. But “objective evidence of the acquired firm’s capability or willingness to develop into such a threat — where available — will also be probative,” the court explained.

Leaving no stone unturned, Schultz was also asked about Instagram’s use-case of friends and family sharing, which is something Schultz said Facebook had to push Instagram co-founder Kevin Systrom to embrace: on re-direct, Schultz said that Systrom was “so focused on the public figure market.”

There was also discussion of a “holdout test.” The FTC asked if this test involved making some users see more friends and family content than others, but Schultz explained that the “holdout” toggled “the tools that we used to help them find more friends and family,” like contact importing. Time spent on Instagram went up by 7% for the group that had the friends and family tools compared to the control group. Instagram follows reportedly increased by 15%, but Schultz couldn’t confirm that. There was also a boost in what appeared to be user retention, from 28% to 35%, which Schultz called “totally nuts,” in a good way. According to Schultz, Instagram had sub-par user retention around the time Meta acquired it.

Here’s a much younger-looking Schultz speaking about user retention:

With that, Mark Hansen took over for cross-examination. We got some more detail on Schultz’s professional background: he worked at eBay, studied experimental physics at Cambridge (England, that is), rowed crew, ran paper airplane and cocktail-making websites, and now serves as a trustee for Wessex Archaeology. And Schultz didn’t miss an opportunity to plug his forthcoming book.

Since joining Meta in 2007, Schultz’s focus has been on growth, marketing, and analytics. Today he occupies two roles, as Vice President of Analytics and Chief Marketing Officer, which carry “separate duties and responsibilities.” Schultz testified that “Mark [Zuckerberg] is very clear that my analytics role is the more important role.” In the analytics role, he’s responsible for internal and external metrics. A team at Meta reviews “all external metrics including those used in lawsuits” to ensure they are accurate. “I say I’m the fairy godmother of analytics,” Schultz said.

Schultz then testified that he sees Facebook and Instagram as competing “for marginal minutes on the service.” The way that apps grow is that first, a user is a monthly active user (MAU); then, a daily active user (DAU); and then, competition moves to time spent.

Schultz thinks that surveys are less important than data about how Meta’s users actually engage with the services. And Meta has “a ludicrous amount of data” from logging things like clicks and actions, which “every web company can save.” Surveys returning “sentiment metrics” help Meta understand brand reputation, but not the “quality” of the apps—they highlight “whatever news cycle is going on right now.”

Trying Not to Suck

Hansen came out swinging against our earlier report that Meta ranked last or near last on the RCAU (Relative Cares About Users) metric, without naming our story, and asked, “Is Meta the worst company” on that score? Schultz said it wasn’t: TikTok and Twitter were “well below” Facebook and Instagram’s scores but sometimes that was statistically indistinguishable. YouTube and WhatsApp ranked above the others, and WhatsApp did well because it didn’t attract negative press. (We’ve since updated that prior headline to reflect the new testimony elicited from Schultz.)

Of course, things still aren’t clear here: Schultz hurt the point Hansen tried to make by equating Facebook with Wells Fargo, the bank that was alleged to have opened unauthorized accounts for existing customers and paid a $3 billion fine to resolve criminal and civil investigations against it by the Department of Justice. Survey head Curtiss Cobb said earlier in trial that “zero RCAU”—which was about Meta’s ranking at least in October 2021—”is around the lowest we think a company can go” as determined “by how people rate the companies they first identify as the worst companies in the U.S.”

First-identified in the contest for worst might also be considered, well, the worst, but it suffices for our purposes to make the more modest claims that, at various times, Facebook was among “the worst companies,” “around the lowest we think a company can go,” below Comcast and sometimes below all of its putative competitors, but perhaps tied with Wells Fargo, the company federally investigated for crimes. We want our reporting to accurately reflect that Meta is sometimes not the worst company according to its own surveys.

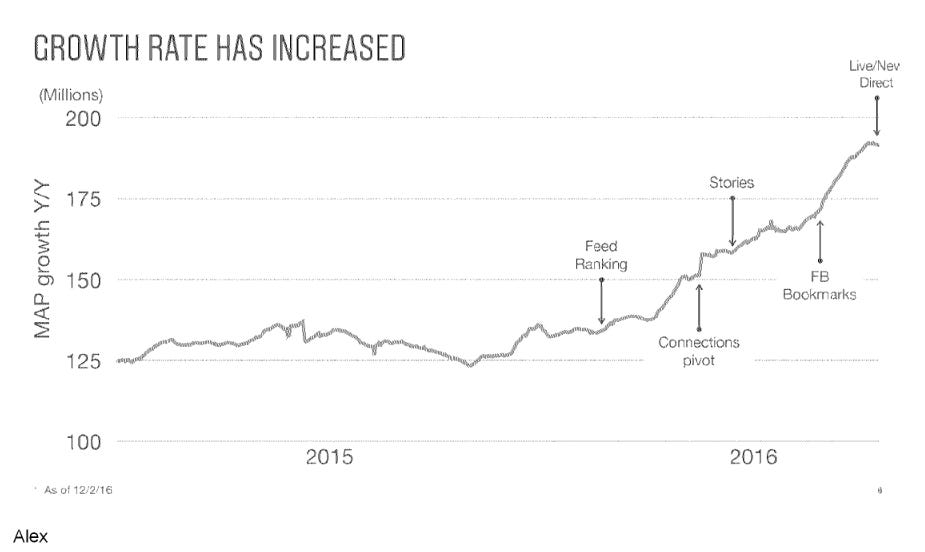

When Schultz returned to the stand at the start of Week 5, on May 12, much of his testimony was under seal, so we don’t know what he said. But he did testify in open court that Instagram’s growth was “explosive,” and he showed various metrics around that:

Schultz admitted that the 2018 imbroglio where Facebook cut off Instagram’s access to Facebook tools caused a 14% decline in Instagram’s growth rate, although Instagram continued to add users. Asked at the end of cross if Meta’s only competition is from Snapchat and MeWe, Schultz said: “I think that’s ridiculous.”

But on redirect, the FTC showed Schultz a 2019 deck titled, “Facebook By the Numbers,” which had a slide supporting the friends-and-family use-case, and also a reframing of the “network effects” discussed earlier:

And yet, once again, the FTC didn’t address a slide in the presentation that hurt its case a few pages earlier. As you read this, keep in mind that the FTC is seeking to show that Meta is in a market of “personal social networking services" that excludes a host of other tech platforms:

Another takeaway here was saturation: growth in terms of numbers of users in the U.S. is slowing because Meta’s apps are running out of users to add. Schultz said that now Meta is competing for users’ time, “because people are multihoming” (using “every app” and cycling between them).

One more mixed document noted competition from TikTok on “interest content consumption” on Instagram, but the pressure was “less evident on consumption of friend content, which begs the question: Are we putting enough focus/energy into defending/evolving key jobs we continue to be hired for?” Put another way: If people liked Instagram because of friends-and-family connection, was Instagram failing its user base?

The FTC finished the redirect with a line of questions about how Meta was understaffing “3 out of our top 4 evergreen surfaces,” a form of restricting output that could help show monopoly power.

Facebook’s Infinite Scroll: Tom Alison

Returning to our regularly sequenced events: The FTC then wrapped with economist expert Scott Hemphill, who was on the stand for three days. We’ve already done an exhaustive report on Hemphill and his “roadshow.” The FTC’s lead lawyer, Daniel Matheson, then called Tom Alison, Head of Facebook. Matheson used the exam to clean up a bunch of issues we’d heard about earlier in trial.

Alison has been with Facebook/Meta since 2010. He started as an engineer on the user growth team at Facebook, helping people find friend connections. In 2013, he shifted to Facebook’s mobile team, working on the native app versions of Facebook. He then started managing product and engineering, amassing more pieces of Facebook in his portfolio before assuming his current role in 2021.

The first exhibit shown in Alison’s testimony noted that “friend content is a differentiator” for Facebook, using language that goes to the heart of the FTC’s market definition theory:

Our primary use case is interaction with friends and family. This is an important differentiator when compared to competition like TikTok and Substack. While we are shifting our app toward Public Content (Interest based Feed & IFR [in-feed recommendations], Reels, etc.) we do want to protect our core use case. . . . Catching up with friends continues to be [an] important use case for our users. In a recent survey, users (including [young adults]) identified that keeping up to date with friends and family is their most frequent intent on FB."

The document suggested that “[f]riend content may be correlated with sentiment.” A “Lorax” survey is something Meta runs periodically to understand user frustrations with Facebook; in the first half of 2021, it found that “3 of the top 4 user pain points were related to friend content.” This cuts against Meta’s attempts to argue that its consumer surveys are just tracking media noise and not product quality. But another experiment to boost friend content by 20% actually resulted in a small drop in usage.

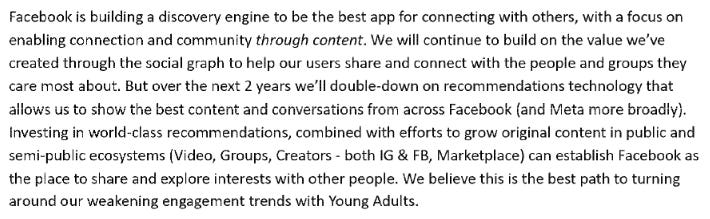

Next up was an exhibit discussing Facebook’s shift toward becoming a “discovery engine.” Alison testified that “the notion of connection is changing. People still want to connect with people they know in real life but increasingly want to connect with people they didn’t know”. But the exhibit showed that this change would still happen in the context of friends and family sharing:

Users “will be able to seamlessly share and discuss this content with the people they care about, in broadcast settings like Feed and Groups, and private settings like messaging threads.” Alison nevertheless testified that friends and family sharing was happening “less and less.” Matheson challenged him in an animated way, pointing out something that had apparently been lost on everyone throughout trial: Setting aside public posts or those from pages or public figures, one cannot simply share a post to someone off-platform on messaging “because you need to be a friend of that person to see the post”.

The exhibit later posed the “natural question” of whether these changes “will dilute our focus on connecting people.” It concluded that “our job doesn’t stop at helping people create or find great content - it requires us to continue building products that allow people to share with one another and deepen friendships and community connections throughout their journey on Facebook.” (Emphasis added.) “Friend and community sharing is important,” Alison said.

On cross, we saw the preceding paragraph from this exhibit, which Meta thinks points the other way:

There was another important question that Chief Judge Boasberg overruled an objection to: “Was it the case in 2023 that Facebook could increase ad load and over the long run increase revenue from a level of 100 to 105?” This was the key question of the exam and one of the key points in the entire trial because it asked if Meta could profitably impose a SSNIP—a small but significant and non-transitory increase in price, which is one way to show monopoly power. Alison added wiggle words but had to agree: he “certainly would have belied it was possible to increase ad load and increase long term revenue” but said Meta wanted to increase quality as well.

Then we got to the “Friends Tab,” something Meta announced on March 27, just weeks before this trial. You can find it on the mobile app, and it shows only content from your Facebook friends. The ad load there is “zero,” said Alison. Here’s Mark Zuckerberg’s Instagram post announcing the feature to that weird, nostalgic music found on some TikTok videos:

This struck me as a belated admission by Meta that the Facebook feed had strayed too far from posts from your actual friends. But there’s one limitation of this tab that went unmentioned: the tab isn’t available on top of the homepage when you visit Facebook on a computer, like this dinosaur does. Alison said that there are “some features from the early days of Facebook that become more interesting as unconnected content grows.” Perhaps another example is the return of the poke in 2024 after the feature had been less prominent in recent years.

Matheson also put up the homepage prompt from Facebook’s website if you are not logged in: “Log in or sign up for Facebook to connect with friends, family and people you know.” Alison claimed that “[j]ust because something is on our website doesn’t mean it’s completely up to date,” as the company was working now to reposition itself. Matheson pointed out that he took the screenshot on April 7 of this year. Alison said that in 2006, the feed was the home page of Facebook. But in 2025, “that feed is in a tab, the secondary experience, not used by the majority of people.” Of course, the Friends Tab had only existed for about six weeks. Alison said of the main feed that “theoretically, you might have to scroll through 10,000 posts” to see all the posts from your friends—”you may have to scroll your feed for an entire day to see the friend content” you want to see.

Chief Judge Boasberg chimed in, wondering aloud whether he was about to offer a “cynical or realistic interpretation,” and then asked if the Friends Tab was “making a big deal of what’s ultimately a side line of friends and family posting or certainly semi-segregating of it to this other place where it’s still available but it’s not the main event”. Alison answered that he “grew up on a Facebook that was all about friend content,” but that we are seeing social media transform “in order to cater to the needs and desires of the next generation”—wanting more creator content, not posting as much, and in turn “transforming what feed is about.” Facebook is just following the trend of what users want. It’s “still going to be valuable to folks including me who use it to catch up with friends,” Alison said, but that use-case is becoming “a supporting part of the cast instead of the main character.” It’s “important to protect it and honor it to some degree as Facebook’s legacy but [it’s] increasingly apparent to me that that’s not where social media” is heading.

Matheson must have been happy with that answer, because he showed Alison this New York Times story that Alison is quoted in from two months ago:

“I wouldn’t have picked that headline,” Alison said. But Chief Judge Boasberg seemed to be buying Meta’s spin at this point. “So this arguably could also enable you on the feed to diminish further the number of friend posts, because to the extent that people” want to see that, they can go to the tab, he said. “If in fact the demand is really for unconnected content, then this sort of lets you have your cake and eat it, too.”

Alison said the “diminishing friend content in feed is less a function of our decision and more a function of the fact that people just don’t want to post to their friends anymore at increasing rates. [It’s] been true for many years.” The court asked if that was because of declining posting or consumption or both. Alison said this is mainly due to declining posting.

According to Alison, there’s a “supply and demand imbalance”: people want to see more posts from friends, but they don’t want to post. “The world is moving to private spaces . . . posting a piece of content in feed might mean you get in an argument about politics with your brother-in-law,” or that you “said something and somebody screenshotted it and you get in trouble at work.” Chief Judge Boasberg said that sounded like “negative network effects,” which Zuckerberg talked about earlier in the trial. The court also asked if we’d know more in six months to a year if time spent on the friends tab suggests that friends and family sharing is the core interest, and Alison answered that there’s not enough data yet to know.

On cross, Kellogg Hansen’s Aaron Panner put up a chart showing an increase in the percentage of MAUs in the United States without a single Facebook friend on day 90 after account creation: the percentages increased from around 10% in 2012 to close to 50% in more recent years. Alison said he would show that slide at an “all-hands” Facebook meeting the next day. The chart sought “to illustrate that Facebook is going through a fundamental transformation” as people increasingly go to Facebook for reasons besides finding friends. On re-direct, though, Matheson pointed out that that data could include professional accounts, content creators, or fake accounts.

Another exhibit showed that 8% of original group posts are now anonymous, and that share is increasing. This exhibit looked at dimensions of competition between Facebook, LinkedIn, Twitter, Nextdoor, and Reddit. Panner pointed to a line early in the deck that “Facebook Groups and Reddit remain the top platforms for meaningful connections to community.” But he didn’t show a slide later in the deck that seemed to directly contradict Meta’s market definition theory:

Panner had better luck asking about TikTok, which seems to have been one of his assignments throughout trial. Alison said that Meta observed that sessions per daily user on Facebook were declining in 2021 before the introduction of Reels, and the “[m]ain thing we attributed declining engagement to was competition from TikTok.” Later in the cross-examination, Alison called TikTok “our most ferocious and challenging competitor” and that Meta “continue[s] to believe that we are losing engagement to TikTok.” When TikTok was briefly offline in the U.S. earlier this year, Facebook saw a “big jump in engagement” on the order of 10-15% in time spent, and a 1-3% increase in DAUs, Alison testified. Alison said the effect on Instagram was even larger, and that TikTok and Instagram “are definitely competitors.”

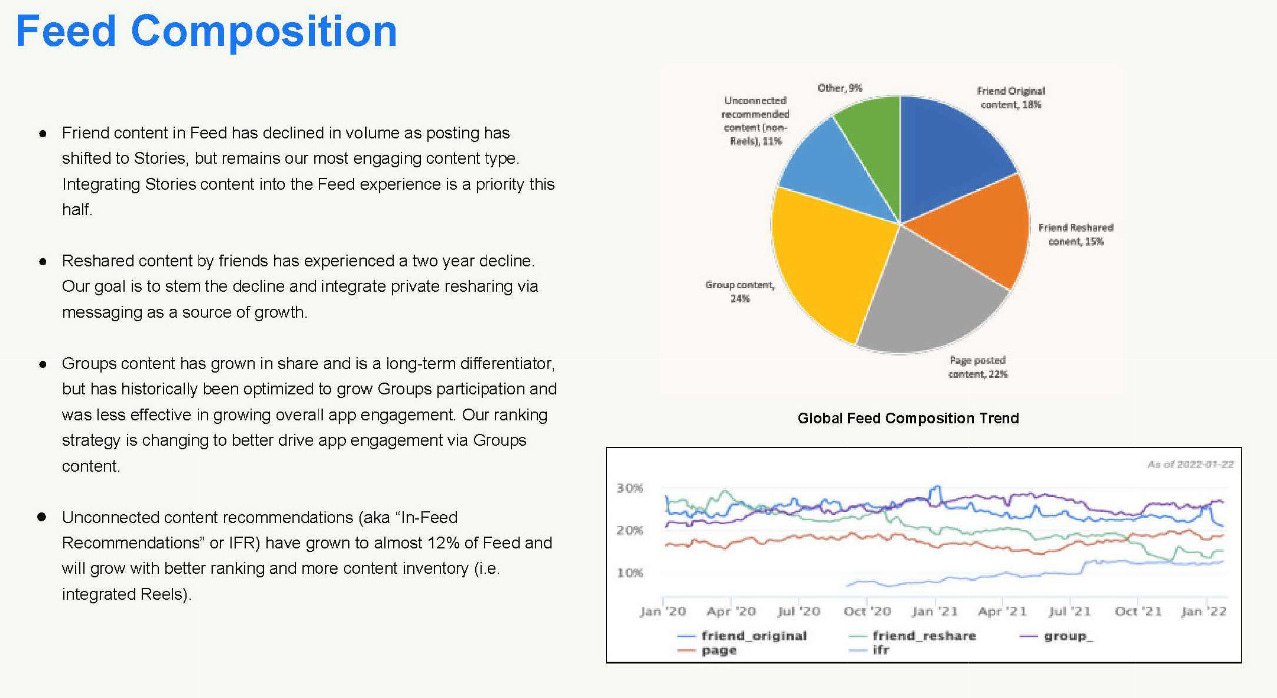

A slide from a March 2022 presentation documented other changes in the composition of Facebook content, with 18% of content made up of “friend original content”—that’s content created by a friend, rather than shared by one. Alison said that the “most significant products from an engagement perspective in recent years” on Facebook were video products. But there again, the exhibit seemed to refute that, as Matheson pointed on re-direct to the top bullet next to the pie chart of content types, which said that while friend content in feed was declining, it “remains our most engaging content type”:

It could be that Alison meant that since 2022, video content has reigned supreme. And Meta competes with TikTok and YouTube to attract content creators for video, for instance. Plus, YouTube influenced Facebook’s strategy “significantly,” Alison said. Asked by Panner about whether Meta underinvested in friends and family sharing features, Alison said that he doesn’t “think that’s true at all,” because there are hundreds of people building new tools (including the friends tab, but also building other things).

Less credibly, Alison claimed that “[s]ome people really like the ads on Facebook. I like the ads on Facebook. I get a lot of ads.” It’s unclear what foundation he had for that statement about others. And Facebook doesn’t set ad load differently based on friends and family sharing content, Alison said. The cross ended with a long speech about how technology changes: books emerged from “monks transcribing them in churches, and then a professional publishing industry emerged.” In a similar way, there’s been a “professionalization of social media” in the form of creators. “I might not want to see a post from a friend I haven’t seen in 30 years about what he ate for lunch yesterday,” Alison said.

On re-direct, Matheson focused on data showing shifts in time spent in 2020 and beyond, asking if Alison knew whether the “number of minutes watched of the NFL went up at the same time and had no effect on Facebook?” Alison didn’t know how to think about that, but pointed out that it’s easier to use Facebook and watch the NFL at the same time than it is to use Facebook and TikTok at the same time. Other data showed that while TikTok minutes were increasing, time spent on Facebook was also increasing, and time spent on YouTube was decreasing. Looking at some more data, as of the end of 2022, friend original and friend reshare content made up a slight majority of all content on the main Facebook feed. Re-direct wrapped up in a sealed session.

The FTC’s Final Witness: Bradley Horowitz

The FTC’s final fact witness of its case-in-chief was Bradley Horowitz, who worked at Google from 2008 until 2023. Until about 2017, he was a VP of product management of products that included Gmail, Google Docs, Picasa, and, as relevant here, Google+, which was Google’s attempt at a personal social network. He led Google+ from 2015 to 2016. On direct, Horowitz explained the Google+ concept of “circles,” which was like a social graph. The FTC’s Albert Teng played this demo video to explain:

Google+ leveraged users’ contact info to help build the social graph. One of Google+’s core use-cases was intended to be connection with friends and family—and Horowitz believed that the same was true of Facebook.

Horowitz’s testimony also shored up barriers to entry, a key part of showing Meta has monopoly power. Horowitz agreed that Facebook enjoyed network effects: “For every user that was on there, it became more and more compelling for the next user to join.” That was a competitive advantage for Facebook. It wasn’t easy to build a social network; it required “a huge amount of lift on a per-user basis.” And there were switching costs: “it was very hard to convince someone to build a social graph where there wasn't a completeness argument.” Users want to go to where their friends and family are. Google+ also offered real user names as compared to traditional Gmail, where users often made pseudonymous email addresses.

The real upshot of the examination was showing that YouTube wasn’t a competitor to Facebook. There was “backlash” when Google at one point required a Google+ account to comment on YouTube, a feature that was “redacted.” And Horowitz agreed that YouTube wasn’t for non-video social sharing:

Q. Taking a step back, why did Google launch Google+ when it already had YouTube?

A. YouTube did not achieve the first goals I mentioned in terms of unifying the social infrastructure across all Google products. So it did not aspire to fulfil that role.

Q. Were there any other reasons Google launched Google+ when it already had YouTube?

A. As I mentioned, we also wanted to create a different destination that wasn't primarily video oriented for sharing [textual] comments, images, group discussions, et cetera, so there were many adjacent opportunities that YouTube didn't address.

Q. Was Google+ intended to be more participatory than YouTube?

A. I would say yes. YouTube is more publisher to consumer, and Google+ was intended to be more peer to peer.

[. . . .]

Q. Was YouTube's primary use case to connect with friends and family?

A. I would say no.

On cross, Meta sought to poke holes in Horowitz’s foundation for his statements: it’s been a while since he worked on Google+, he didn’t know a lot about Facebook, didn’t work on YouTube, and so on. Meta’s counsel also highlighted the difficulty Google had in getting Google+ off the ground. By the time it was sunset, Google+ “no longer had the opportunity, talent, resources, the ingredients to get it over the line to viability.”

After a brief re-direct, Horowitz stepped down, and the FTC rested its case-in-chief.

Up Next

We’ll bring you the summary of Meta’s case in our next post.

We know Meta controls your news feed meaning they can pretty much set how much time users spend on Friends/Family. That said who has verified the data regarding the amount of time users spend viewing 'Friends and Family' posts? Are we solely relying on Meta's self-reported data for this information? Does it include the time spent going directly to Friend/Family profiles to see all posts they missed since Meta has stopped putting Friends/Family stuff in the feed.

Can Meta compete with other companies (Tiktok and Youtube) and decide those companies are now competing with Meta? Couldn't Meta have remained just a PSN social network? Especially given Tiktok and Youtube are not PSNs.

Meta's violation of antitrust laws started in 2012 when they bought Instagram to avoid competition that might have kicked their tail. There was no Tiktok then. Tiktok posses no threat to Meta's PSN social network.

Can Meta's ambition save them from an antitrust violation?

Facebook has Facebook Marketplace too. Why not include Ebay and Amazon as competitors too then.

Seems like Antitrust law on market definition is all over the place if it allow Meta to tell us who their competitors are based on their ambition. Why not include OpenAI too?

I dont know if this was mentioned at trial but in 2012 Meta itself was having trouble making an App. This should have been mentioned at trial but I think it wasnt. or at least I dont know. Facebook made an HTML5 website they thought would be fast enough on mobile phones and it wasn't. They did not make an App. They were caught with their pants down when competitor Instagram came up with a speedy app that kicked their butt. It took Meta (Facebook) at least a year to fix their problems on mobile. There was panic at Facebook. Mark probably would have paid any amount for Instagram in 2012. He was scared and losing. Mobile was the future and Instagram owned it. He was stuck with HTML5 and didnt even have a good mobile app developers. He was at least a year behind.

This history -- did it come out at trial?

https://www.quora.com/Why-did-Mark-Zuckerberg-say-that-choosing-HTML5-for-mobile-app-was-a-mistake

note: Facebook's friends tab works very differently than Instagram's friend tab. On Instagram it's more about seeing what content your friends are interacting with rather than their direct posts.

Facebook knows they have Friend and Family under lock and key. They own it.

Now they want to compete with Tiktok and even Amazon.

https://www.cnbc.com/video/2025/03/08/how-facebook-marketplace-amassed-more-shoppers-than-amazon.html

Does that allow them to say they dont have a monopoly?

Its bull to say social is changing; its all under Meta.

Meta has it all locked up between Facebook, Instagram, and Whatsapp.

Friends/Family is the core of all of Meta's power.