From "Roadshow" to Expert Witness: Courtroom Drama As FTC's Economist Finally Takes Stand

The Meta antitrust trial entered Week 5 with Meta marketing head Alex Schultz on the stand again, before the FTC finally called its economist. Sparks flew.

In 2019, according to reports in The New York Times and the Washington Post (reprinted here), three men went on a “roadshow” to federal and state antitrust enforcers laying out what a potential antitrust case against Facebook could look like. They were Chris Hughes, Mark Zuckerberg’s former Harvard roommate and fellow Facebook co-founder, who became a critic of the company after leaving; Tim Wu, the Columbia Law professor who served as a Special Assistant to President Biden for Technology and Competition Policy; and Scott Hemphill, an NYU Law professor and Ph.D. economist.

The roadshow worked. In the last days of the Trump administration, in December 2020, the FTC and 48 States sued Facebook for violating the antitrust laws with its acquisitions of Instagram and WhatsApp. Two years after that, the FTC retained its expert economist: Scott Hemphill, who took the stand on Days 17, 18, and 19 during the fifth week of the trial to break up Meta.

The story of how the Facebook case came to fruition took center stage during Meta’s cross of Hemphill on Day 18, as lead defense counsel Mark Hansen tried to paint Hemphill as a “law professor” with an “axe to grind.” Hansen made the point with a newly revealed document he said the FTC never produced to Meta: a slide deck from the “roadshow” presentation, as shown in pictures of a smartphone displaying those slides. It was an explosive behind-the-scenes look at how the sausage gets made.

But before we get there, let’s go through Hemphill’s direct examination, which featured frequent questions from Chief Judge Boasberg. This email is overlong, so be sure to click to expand the message to see the whole thing or open it in the app or on the web. We’ll catch you up on testimony from Meta’s Alex Schultz, plus Meta’s Tom Alison on Day 19, in a future post. This post covers all three days of Hemphill.

What the FTC Has to Show

We discussed the FTC’s burden of proof before trial started and previewed some of the key arguments on market definition in our Day 1 summary of opening statements. But to briefly restate: to prove its monopolization case under the Sherman Act, the FTC must prove that (1) Meta has monopoly power in a relevant market and (2) that Meta gained or maintained that power through something other than competition on the merits.

In this case, the FTC alleges that Meta has been a monopolist since the early 2010s and illegally maintained that monopoly by acquiring Instagram and WhatsApp. The FTC bears the burden of persuasion, but the standard is simply more likely than not, or a hair above 50%, which is a much lighter lift than the beyond-a-reasonable-doubt standard in criminal cases. Hemphill’s testimony on Day 17 focused on the relevant market.

The first thing you should know is that there’s some disagreement over whether the FTC needs to define a market at all to show monopoly power. Monopoly power is understood as the power to profitably raise prices above a competitive level and to exclude competition. Here’s how I explained that to the Wall Street Journal in the context of the Department of Justice-led antitrust suit against Apple:

That interview video cut my discussion of direct evidence. But the FTC can meet its burden of proof to show that Meta is a monopolist with direct evidence of monopoly power: evidence that Meta can profitably impose prices above, or output or quality below, a competitive level. Because of the difficulty in establishing the competitive price or quality level in a monopolized market, a problem Hemphill flagged, it can be difficult to prove monopoly power with direct evidence. So even though Hemphill has some arguments about direct evidence, his Day 17 testimony started down the path of proving monopoly power with indirect evidence. Indirect evidence entails a “structural” analysis of a market: (1) defining a relevant market, (2) showing that the defendant has a dominant market share in that market, and (3) showing the existence of barriers to entry that make it so that potential competitors cannot readily challenge the defendant.

Sound complicated yet? We’re just getting started. There are legal rules around defining a relevant market, too. When we say “relevant market,” we really mean “the area of effective competition,” which has two components: a geographic market and a product market. In other words, the relevant market is made up of (a) things sold or exchanged (b) in a place. Everybody seems to agree that the relevant geographic market here is the United States. The parties dispute the product market.

Case law says that the product market is determined “by the reasonable interchangeability of use or the cross-elasticity of demand between the product itself and substitutes for it.” And all that economic jargon means is that a product market must include all reasonable substitutes—the other products that consumers will switch to when faced with a “small but significant increase in price” (or quality decrease) for one product.

In language the FTC keeps highlighting, the opinion in the Microsoft appeal said that a market must include “all products reasonably interchangeable by consumers for the same purposes." For the FTC’s proposed market definition—“personal social networking services”—an app’s purpose matters. Sharing updates with your family and friends is different from watching videos posted by strangers.

Hemphill’s Hypothetical Monopolist Test

Hemphill is a professor at NYU Law. He joined the faculty there from Columbia Law. He has an interesting background in that he’s both an economist and a lawyer. He clerked for Judge Richard Posner and then Justice Scalia, and later served as chief of the antitrust bureau in the New York Attorney General’s office. (Meta’s lead lawyer Mark Hansen objected at several points to questions that would have Hemphill discuss the facts of prior antitrust cases, claiming that testimony about that amounted to an improper legal opinion from a law professor. Chief Judge Boasberg overruled those objections.) Hemphill, for good measure, also has a Ph.D. in economics from Stanford. His work on “pay-for-delay” settlements in patent litigation was cited by the Supreme Court in the Actavis case. It was on the basis of that economic experience that he was certified as an expert in industrial organization economics.

Hemphill defines the market that we’d heard about throughout trial: the personal social networking services (“PSN”) market. To get there, he claims to use something called the Hypothetical Monopolist Test (or “HMT”). The Hypothetical Monopolist Test groups products within a candidate market and asks whether a single firm with control of all producers of the market could profitably raise price above—or diminish quality below—the competitive level. This is most often expressed by asking whether the hypothetical monopolist could impose a Small but Significant and Non-Transitory Increase in Price (“SSNIP”), and can be modified to examine a decrease in quality. Two key words there are “small” and “non-transitory,” as we’ll cover in a moment. Hemphill had some trouble getting the acronym right on direct, drawing a smile from the FTC’s lead lawyer Dan Matheson, but Hemphill eventually found his footing. So if the alphabet soup is a lot to digest, rest assured that even former Supreme Court clerks turned Ph.D. economists get them wrong sometimes, too.

Hemphill couldn’t do this traditional test asking if the hypothetical monopolist could impose a SSNIP because users do not pay Facebook or Instagram money to use the apps—there are no “prices” and therefore no price data from which to model a 5% price increase. At summary judgment, the court called “halfhearted” the FTC’s “attempt to repackage Hemphill’s analysis as a thoroughgoing HMT,” and said that his analysis would “overlap substantially” with the qualitative factors for market definition from the Brown Shoe case. Another complication to a straightforward HMT is what’s called the “cellophane fallacy,” explained here, where more distant substitutes are erroneously included in the market if the SSNIP is measured from a monopoly price baseline, instead of from the competitive level.

But “zero price doesn’t mean competition is suspended,” Hemphill explained. Instead, competition takes place “along other dimensions” of quality, like ad load (the percentage of impressions that ads make up of all content a user sees), the volume of users’ data collected, investments in friends-and-family content, and integrity (trust and safety, reliability, and so on).

So Hemphill’s qualitative HMT asks if a single firm controlling Facebook, Instagram, and the other PSN apps (Snapchat and MeWe) could profitably lower quality from the competitive level. He found that the hypothetical monopolist could, signaling the soundness of the FTC’s proposed PSN market.

The failure to do a quantitative SSNIP is something critics of the case point to. But the current Merger Guidelines, adopted by the FTC and Department of Justice in 2023, speak of “qualitative and quantitative evidence and tools” (§ 4.3C), suggesting that a qualitative HMT is enough.

Hemphill also seemed to agree with the “smallest market” principle that Chief Judge Boasberg explained at summary judgment. I thought the “smallest market” principle was put well in written testimony from Frederick Warren-Boulton, one of the economist experts for the government in the United States v. Microsoft antitrust trial in this same courthouse:

“Thus, the Guidelines’ hypothetical monopolist inquiry begins with a product (and geographic area) that the relevant firm produces and asks if the hypothetical monopolist could exercise power over those products. If the answer is ‘no,’ the market has not been drawn broadly enough; other forces would defeat the hypothetical monopolist’s attempt to exercise market power. In such circumstances, the next closest substitute for the product considered is added, and the question of whether the hypothetical monopolist could exercise power in this possible market [is] asked again. This process is repeated until the answer is ‘yes’; at that point, the market has been properly defined. Completing the analysis at the earliest point at which the hypothetical monopolist could exercise power is known as the ‘smallest market principle.’”

Defining the smallest market, and not the largest market, is important. From Meta’s vantage point, competition happens between its apps and others like TikTok for users’ “time and attention.” But Chief Judge Boasberg said in his summary judgment ruling that “competition between Meta and other social-media firms for users’ time and attention does not necessarily make them part of the same relevant product market.” The court cast doubt on this theory in another passage (emphasis added):

“Meta’s extensive evidence of head-to-head competition outside the PSN services market therefore does nothing to show that its proposed ‘time and attention’ market is the only relevant antitrust market. Indeed, if the Court were to credit Defendant’s preferred market, it sees no obvious limiting principle: when it comes to so broad a market as ‘time and attention,’ Meta competes not just with YouTube, TikTok, and X, but also with watching a movie at a friend’s house, reading a book at the library, and playing online poker. Antitrust law does not require consideration of such an ‘infinite range’ of possible substitutes.”

To sum up: the relevant market has a geographic component and a product component. The economist starts with a candidate product market and adds products to that market one by one, asking whether a hypothetical monopolist of all those products could profitably raise price above the competitive level, or here, degrade quality below that level. As soon as the hypothetical monopolist can, the market definition line is drawn, and that market becomes the area of study for competition, even if there are other, broader markets that might exist.

The point of all of this isn’t to define a market for its own sake but to use the proper framework for evaluating whether Meta is a monopolist and whether gobbling up Instagram and WhatsApp helped it stay one.

Hemphill’s Qualitative Market Definition Analysis

With that background in mind, Hemphill took us on a tour of data and testimony supporting the PSN market. Inside that market are Facebook and Instagram, plus Snapchat and MeWe (a smaller competitor). Meta has tried to mock the inclusion of MeWe throughout trial as unimportant, but Hemphill explained that they have a PSN product and it’s conservative to include them in the market even if they’re not a big player. TikTok, YouTube, iMessage, and Twitter/X, four of the leading potential competitors we’ve heard about, are outside that market, as illustrated below:

Hemphill started out by explaining features of PSN apps at a high level. They are characterized by “network effects,” an economic term for a product that changes in value as the number of its users changes. In the case of social networks, when more of a user’s friends and family are on the app, the app is more valuable to users. And the more users there are, the more valuable that platform is to advertisers. Network effects can also make it difficult for rivals to enter and compete because they need to reach a critical mass or minimum scale of users to make joining the platform worth it.

Then Hemphill turned to “core use-cases.” There’s lots of evidence that the core use-case for Facebook is to see updates from friends and family. TikTok and YouTube, by contrast, have a core use-case of watching video. Facebook and Instagram are built around a social graph, but TikTok is built around a content graph. Those different purposes are reflected in the data: on Facebook and Instagram, the share of reciprocal or “mutual” connections is 64% and 42%, respectively, vs. lower percentages for TikTok and X/Twitter, which were redacted on the public exhibit:

Hemphill found that the average American on Facebook in 2022 had 458 friends, more than 15 times as many connections as the average U.S. user of TikTok. Putting the lie to something we had heard earlier in trial that there were Facebook users with no friends, Hemphill showed (during one week in April 2022) that 1.5% of Instagram accounts had no friends or accounts followed; on Facebook, that figure was 0.5%—so there aren’t many people joining Meta’s apps just for Reels.

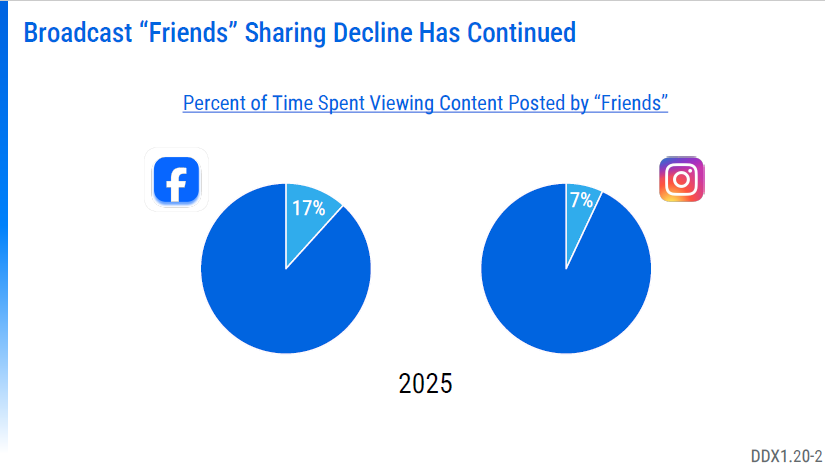

Chief Judge Boasberg asked later on whether the market has to encompass the product’s core use-case, or if there could be a monopoly in how people use the product only 10% of the time. He must be thinking about this slide we saw in Meta’s opening, which shows “time spent viewing content posted by ‘friends’” makes up 7% and 17% of time spent on Instagram and Facebook, respectively:

“Imagine any old business that was a monopoly and then built something else,” Hemphill answered. He cited AT&T’s long-distance business as an analogous situation where a firm becomes increasingly diversified but nevertheless is broken up for being a monopolist. Chief Judge Boasberg also asked a question he has asked other witnesses: whether the difference between Meta’s apps and video apps like TikTok is a difference in degree or kind. Hemphill testified that they were different in kind because Meta had the friends and family sharing use-case.

We saw some new evidence supporting the idea that the PSN use-case is focused on content from connections. Using Meta data from April 24 through 30, 2022, Hemphill found that less than 1% of Facebook users and 5% of Instagram users open the apps and spend less than 30 seconds on the main feeds:

Chief Judge Boasberg questioned these statistics since all users have to see the main feed when they open the app. And, he added, the feed is no longer just friends and family content anyway—there’s “plenty” of unconnected content, so “is it even fair to say” that the time spent on the feed is time spent on friends and family content? Hemphill replied that the default feed isn’t “given by God” but something Meta designed, probably because it recognizes the core use-case of friends and family sharing. He also pushed back against Meta’s claims that users enjoy seeing relevant ads as much as or more than seeing organic content from other users.

Shocks & Messaging

Further confirming the PSN core use-case of friends and family sharing, Hemphill found that PSN apps see spikes in usage on holidays, but other apps don’t to the same extent. That’s especially true of Mother’s Day, which topped a chart we saw for what appeared to be usage data, and came the day before Day 17. There were similar spikes for other holidays:

Chief Judge Boasberg then jumped in to ask Hemphill about the natural experiments or shocks we saw in Meta’s opening statement showing that users shift time to TikTok and other apps when Meta apps are down and vice-versa. Hemphill responded with the points we flagged in the opening: that the blackouts are transitory (instead of non-transitory as in SSNIP) and involve an “infinite” quality change (disappearing) rather than a “small but significant” change from the competitive level, two characteristics that would tend to make the relevant market broader than it should be.

Questioning then turned to why messaging apps like iMessage are outside the PSN market. Apple wants to use iMessage as a differentiation tool for selling its hardware. What Hemphill could have said more clearly but came out earlier in trial was that Apple probably wouldn’t license iMessage for use on non-Apple devices, which in turn means iMessage has limited potential for becoming a PSN service. Before Day 17 ended, Hemphill returned to TikTok, closing by testifying that it competes with a piece of what Meta does but not against all of what Meta does; in particular, friends and family sharing.

Direct Evidence

Hemphill came back for the continuation of his direct examination on Day 18, and he started by discussing direct evidence of Meta’s monopoly power. Hemphill identified five categories of direct evidence: sustained high economic profits, increased ad load, price discrimination, degrading quality, and the lack of substitution away from Facebook after the Cambridge Analytica scandal:

The economist returned to something we’d heard suggested throughout trial, that Meta can engage in price discrimination by showing different quantities of ads to different users. That’s in effect a form of price discrimination (or quality discrimination) because the time a user spends watching ads is in effect a “time tax”—the more time they spend watching ads, the greater the tax. The ability to price discriminate can help show monopoly power because it requires some degree of market power to implement. Of course, monopoly power is something more than market power, and firms may enjoy a degree of market power just from having differentiated products. Put another way, we expect that monopolists can price discriminate, but not all firms that can profitably price discriminate are monopolists. So the evidence of price discrimination isn’t dispositive, but it’s one data point supporting monopoly power.

One form of price discrimination was Meta’s varying of ad load for “needy users,” a term we heard mentioned with Meta’s John Hegeman. Needy users drop off in app engagement more than other users do when shown more ads. Meta’s interrogatory response defined “needy users” as those who are “new, stale, or at risk of going stale.” Testimony from Meta executives earlier in trial seemed to confirm that responsiveness to ads is one factor that goes into “dynamic ad load,” which is Meta’s name for its ability to vary ad load.

Meta profitably degraded quality, Hemphill claimed. We saw a chart plotting the survey results from the question, “How much control do you have over your personal information on Meta’s apps and products?”, with a line going down between 2018 and 2022:

There were declines for other metrics like “Cares About Users” and “Good for the World,” too. Chief Judge Boasberg had Hemphill confront what we’d heard from Meta executives that those metrics seem to be driven by media cycles, and asked if there’s any evidence that Meta had done anything to lessen people’s control over their information. Hemphill cited the Cambridge Analytica scandal as something “media driven but . . . reporting an actual reality.” Data from that time showed that despite plummeting user sentiment, daily active users and time spent on Facebook remained fairly constant, showing the absence of reasonable alternatives. Meta executives used these surveys "for product experience,” Hemphill said.

Market Shares & Entry Barriers

After wrapping up the line of questioning on direct evidence, the FTC moved back to the indirect evidence, starting with market share. Now I’ve been debating with professor Herb Hovenkamp, who wrote the leading antitrust treatise, about the market share that a plaintiff has to show to establish monopoly power. This is a useful statement of the law on that from the Second Circuit, the federal appellate court that covers New York:

"Sometimes, but not inevitably, it will be useful to suggest that a market share below 50 percent is rarely evidence of monopoly power, a share between 50 and 70 percent can occasionally show monopoly power, and a share above 70 percent is usually strong evidence of monopoly power.”

Broadway Delivery Corp. v. United Parcel Serv., Inc., 651 F.2d 122, 123 (2d Cir. 1981)

Other case law says that a prima facie case requires a market share of 65%. Hemphill counted market share three ways, by share of monthly active users (“MAUs”), daily active users ("DAUs”), and time spent. By those measures, Meta’s market shares were 78%, 77%, and 85%, respectively. As a sensitivity analysis, Hemphill looked at results from four consumer surveys, which found Meta’s “prorated” market share to range from 69% to 78%. And recall from Meta’s opening that even if TikTok makes it into the relevant market with Meta’s apps, that would only reduce Meta’s market share to 60% of time spent, which could be enough as the above case law suggests, if there are barriers to entry.

Hemphill testified that there were barriers to entry and expansion, such as “switching costs,” which refer to what users would need to do to use a competing PSN app. A consumer considering an alternative app might have to replicate all their photos, a cost of switching that can deter users from trying. Hemphill showed how Facebook users accumulate more photos over time, making it less likely that they will switch to a competitor. Another switching cost is the inability to replicate your connections, or network, on another app. Anyone who has contemplated switching from Twitter to Mastodon or Bluesky can probably relate.

Anticompetitive Effects

The direct examination moved to anticompetitive effects, but first the FTC gave Hemphill an opportunity to respond to the theme we’ve heard from Meta executives throughout trial that “only the paranoid survive,” a way to contextualize emails that seem concerned about the competitive threat from Instagram and WhatsApp. Bill Gates was paranoid at some level about competition from Netscape, Hemphill reminded the court. There can be a rational basis underlying that paranoia—wanting to protect monopoly profits, as even a low probability of competition puts substantial money at risk. And, Hemphill pointed out, the phrase originates from Intel CEO Andy Grove, and Intel itself has been investigated and sued for monopolization.

The main anticompetitive effect flowing from the deals was the elimination of head-to-head competition between WhatsApp/Instagram and Facebook, Hemphill said. At that point, Chief Judge Boasberg asked Hemphill to respond to something we heard from Meta’s marketing head Alex Schultz, and other witnesses, about the explosive growth of Instagram post-acquisition. It’s “hard to grow much more than it’s grown in the U.S.,” Chief Judge Boasberg said—the market has been saturated and there are not many more users to find. Hemphill said he wasn’t opining that “Meta made no contribution to Instagram’s growth,” but that the relevant question was what growth would have looked like in the “but-for world,” the world that would have been had the acquisitions not happened.

Hemphill testified that Instagram was successful without Facebook, and in the but-for world, other firms would have provided Instagram with the tools that Facebook gave it. But then Hemphill sounded inconclusive, saying that “[w]e generally don’t know what would have happened.” Instagram “might have been smaller” or bigger. But that didn’t matter, Hemphill said, because the question that matters for anticompetitive effects isn’t just output, but “consumer surplus,” the value that consumers get above the price they pay (which here is time spent watching ads). Instagram increased its ad load over time on the feed, from .3% in Q2 2015 to 6.9% in Q2 2016, to 10.9% in Q4 2017, and to 18.5% in Q1 2019:

We saw slides showing that Facebook’s ad load in North America exceeds 20%, and Instagram’s exceeds 15%:

Another claimed anticompetitive effect was that the acquisitions let Meta build a “competitive moat” around its PSN apps. But Chief Judge Boasberg sounded skeptical: “It seems that this competitive moat [is] a minor factor” in Meta’s decision-making given the investment in Instagram and explosive growth there. Hemphill answered that at the time of the acquisitions, the evidence was that the strategy was to build a competitive moat, which the court characterized as going “to intent at the time.”

Procompetitive Justifications

The final portion of Hemphill’s direct previewed a rebuttal to Meta’s claimed procompetitive justifications for the Instagram and WhatsApp deals, which include improving monetization, infrastructure, integrity, and cost savings, among other things. By Hemphill’s estimation, a valid procompetitive benefit must be “passed through” to consumers and must “depend on the acquisitions for its achievement”. That allowed Hemphill to dispute improved advertising as a benefit: high advertising profits don’t help users, who would prefer not to see ads.

Chief Judge Boasberg posed an insightful question on that score: if WhatsApp and Instagram would have monetized if they weren’t acquired by Meta, as Hemphill claims, doesn’t that mean that increased ad load was inevitable, and so not dependent on the mergers? Hemphill said that Instagram could have covered its costs and earned a profit without increasing ad load to 20%.

There were also questions about why WhatsApp dropping its subscription fee to nothing after Facebook acquired it doesn’t count as a procompetitive benefit. Hemphill responded that the cost savings would happen outside the PSN market among messaging users, so wasn’t part of his assignment, which was analyzing competition within the PSN market.

This gets to a broader debate happening in the law right now about whether procompetitive benefits outside the relevant market can rebut anticompetitive effects within the market. As Judge Mehta recently noted in his Google Search monopoly liability opinion (see discussion at page 255), “the Supreme Court’s precedent on cross-market balancing is not clear.” And in that case, weighing procompetitive benefits in related markets wasn’t necessary, because Google’s exclusive agreements did not produce procompetitive benefits in those markets at all, the court explained.

An Expert With “An Axe to Grind”?

Meta’s lead lawyer, Mark Hansen, started cross examining Hemphill with a deposition admission we saw from Meta’s opening statement:

Hemphill initially tried to say that the answer isn’t “easily boiled down to a yes or no.” The issue here is that if everything on a PSN app is part of PSN usage, that includes short-form video, for example, which is also available on TikTok, YouTube, and other apps.

Without naming the case, Hemphill started echoing the argument the FTC made in its challenge to the acquisition of Wild Oats by Whole Foods: “Suppose you go into Whole Foods and buy batteries or water. You are engaged in shopping in a ‘premium natural [and] organic supermarket’”—the words used by the FTC to define the market in the Whole Foods case—“even though you’re not at that moment buying organic mangoes,” Hemphill said. Although Whole Foods competes with traditional grocery stores over dry groceries, that doesn’t mean those stores compete with Whole Foods for organic perishables.

In the same way, although TikTok might compete with Reels on Meta apps, for instance, it doesn’t compete with the special sauce Meta is offering: friends and family sharing. In the Whole Foods case, though, perishables were 70% of Whole Foods’ business, but friends and family sharing time makes up far less of user time spent on Meta’s apps, as activity has shifted to unconnected content—below 20% on Facebook and below 10% on Instagram as we saw in Meta’s opening.

Then Hansen turned to a module designed to show that Hemphill has a preexisting bias against Meta, focusing on Hemphill’s 2019 “roadshow” with Tim Wu. Hansen began this section asking value-judgment questions that were hard to disagree with. Of course, they were a trap for what was coming next. Experts are supposed to “report with objectivity” and not “support preconceived notions, correct?” Hansen asked. Hemphill agreed. Expert witnesses have a duty “not to seek employment as an expert witness” in a case, right? Hemphill didn’t know, but wasn’t “troubled” by that idea.

“An expert with an axe to grind is not useful to the finder of fact and becomes another advocate for the party, right?” Hansen asserted. Hemphill agreed that sounded reasonable. But “you are the very definition of an expert witness with a partisan axe to grind,” Hansen charged. Chief Judge Boasberg shook his head a bit at that; Hemphill disagreed.

“So isn’t it true that you, a gentleman named Tim Wu, and another gentleman named Chris Hughes, took a roadshow to enforcers, including the DOJ, the FTC, and State AGs in the summer of 2019 and advocated for those enforcers to bring a case against Meta?” Hansen asked. It was quite a surprise.

Hemphill said that wasn’t “quite right.” He admitted that they spoke with those enforcers, but it was “without prejudicing the outcome.” Hansen then launched into a series of questions that raised considerable doubt that what Hemphill said was true.

Hansen showed a New York Times story from 2019 where Hemphill is referenced as a source, though not quoted verbatim (emphasis added):

In recent weeks, Mr. Hughes has joined two leading antitrust academics, Scott Hemphill of New York University and Tim Wu of Columbia University, in meetings with the Federal Trade Commission, the Justice Department and state attorneys general. In those meetings, the three have laid out a potential antitrust case against Facebook, Mr. Wu and Mr. Hemphill said.

Hemphill said he was probably being misquoted here, but agreed that they had meetings. Hansen pointed out that Tim Wu was actually in court for Day 17 during Hemphill’s direct, even “Tweeting out his thoughts about the testimony”:

Hansen characterized Wu as biased based on a statement from his book, The Curse of Bigness, and Chris Hughes as biased from his admitted effort to break up his former company. In a part of the Times story we didn’t see, Hemphill—discussing precedent cases like Standard Oil—seemed to preview his view of what should happen to Meta: “There is a direct connection between the conduct and the remedy — undo the acquisition.”

Hansen put up another press clipping, this time from the Washington Post:

“Soon after, Mr. Hughes was contacted by two prominent antitrust scholars, Mr. Scott Hemphill of New York University's law school and Mr. Tim Wu of Columbia University's law school. The two academics and longtime collaborators had been developing an argument for breaking up Facebook.

To them, the purchase of Instagram and WhatsApp represented a ‘plain vanilla violation of antitrust law, just low-hanging fruit,’ Mr. Wu said in an interview. They began to pitch lawmakers and regulators together.”

Does that sound like someone prejudging the outcome or not? Hansen was also trying to show that Hemphill contacted Hughes to work together, but Hemphill again claimed this was incorrectly written. No, Hemphill hadn’t sought a correction, he admitted. Hansen argued through his questions that Hemphill was trying to gin up the case to make the “millions of dollars” he’s been paid to work on his expert report and give his testimony here.

In his deposition testimony and again at trial, Hemphill made it sound like these were some one-off meetings that didn’t lead anywhere, and that he and Wu hadn’t concluded that Meta had violated the antitrust laws. But there is even more public material that Hemphill and Wu’s advocacy against Meta continued after the summer of 2019.

In June 2020, Hemphill and Wu co-wrote an article that would be published in the University of Pennsylvania Law Review titled, Nascent Competitors. Facebook’s acquisitions of WhatsApp and Instagram were discussed throughout. Consider these statements, and whether they are neutral or prejudging the outcome (emphasis added):

“When the parties say something specific and detailed about their anticompetitive plan, we should believe them. Leading examples include . . . Facebook’s detailed internal assessments of particular threats and what to do about them.”

“WhatsApp posed a nascent competitive threat. In 2014, it was not a fully fledged social network. The competitive concern was that WhatsApp might ‘morph into Facebook’ over time. Facebook acquired WhatsApp for $22 billion, thereby eliminating the threat.”

The FTC and 48 States filed the Meta suit on December 9, 2020. The next day, Hemphill was quoted in a press release issued by New York Attorney General Letitia James, and what he said sounded like somebody who had already reached a conclusion (emphasis added):

“Facebook’s idea that 'it is better to buy than compete' is totally contrary to the letter and spirit of antitrust laws,” said Scott Hemphill, Moses H. Grossman professor of law, New York University. “Dominant firms have to compete on the merits with innovative startups that are emerging rivals, not buy them up. This litigation is important to restore competition and protect innovation in social networking and beyond.”

Also on December 10, Wu and Hemphill published a Medium post titled, “Three things the press keeps getting wrong about the Facebook antitrust case.” The day after the case was announced, Hemphill and Wu concluded that Facebook was a monopolist (emphasis added):

“In 2012, the durability of Facebook’s monopoly was unclear, and it was widely thought that Google+ would emerge as a major competitor to Facebook. But here in 2020 we know that the monopoly was durable, and that Google+ was not significant.”

Ironically, in that piece, Wu and Hemphill took journalists to task for relying on “a paper funded by Facebook and published in a corporate-funded journal” for the proposition (wrong in their view) that the FTC would have to prove that Instagram or WhatsApp would become “significant” competitors—without disclosing their own meetings with enforcers.

A Mountain Out of A Hemphill?

Hansen skipped over these statements in favor of introducing the “roadshow” presentation itself. Hansen said the FTC hadn’t produced it, but we learned on re-direct that Meta never asked Hemphill for it. The exhibit appeared to be photos taken of the deck as shown on a smartphone; someone’s fingers were visible in the photos. Hansen zeroed in on the language, “direct evidence of anticompetitive intent.” One of the cited sources was to this 2019 story in the New York Post, which seemed to preview this email as shown in the FTC’s opening statement slides:

Hansen, though, asked if the Post was a “scandal sheet,” before putting up this (in)famous Post cover page as a demonstrative exhibit. Other sources listed included Kara Swisher. Hansen referenced her post—on Threads, no less—that called Mark Zuckerberg “a small little creature with a shriveled soul,” among other things. Wasn’t that evidence of bias? One problem with Hansen’s point is that Swisher’s post is from January 2025, six years after she was cited as a source in the “roadshow” deck.

But the deck had other problems. It misstated the acquisition price of WhatsApp as $22 billion; it was $19 billion, Hemphill admitted. It said Twitter had made a $500 million offer to acquire Instagram; Hemphill said a $500 million benchmark valuation for Instagram was based on a venture capital analysis, which Sequoia partner Roelof Botha testified to earlier at trial. Hansen also questioned the deck’s suggestion that Instagram co-founder Kevin Systrom had misrepresented acquisition interest from Twitter in testimony before a government agency.

Ultimately, my view is that it was a strange choice to retain as an expert witness someone who was meeting with enforcers to lay out an investigation or litigation. It’s not as though Hemphill is alleged to have changed any views, only to have prejudged Meta. But the expert’s credibility is the coin of the realm. Even if Hemphill didn’t reach any conclusions in his “roadshow,” not being affirmatively forthcoming about it made the credibility problem worse.

Perhaps the most impactful questions on that front came from a demonstrative Hansen put up of stills from the same video across TikTok, Reels, and YouTube Shorts. He then asked Hemphill to name which photo showed which app. Hemphill couldn’t tell. It was an effective gambit that overlapped with Meta’s substantive point that the apps are interchangeable for short-form video consumption.

Getting Crosswise

Next on cross, Hansen showed that Hemphill used data from Comscore and other sources that list other apps like Twitter, TikTok, and Pinterest along with Facebook and Instagram in a social media category, qualitative evidence that could support the apps being in the same relevant market. Cross soon entered a sealed session for much of the rest of the afternoon.

On Day 19, when cross resumed after a sealed session, Hansen got into consumer sentiment surveys. One point his questions were making that sounded new to me was the suggestion that respondents in some Meta surveys are not prescreened for their past experience with brands surveyed. “Asking a vegetarian about the quality of Chick-fil-A wouldn’t be very informative,” would it? Hansen asked.

Later, Hansen tried to discredit Hemphill’s opinions that Meta’s high economic profit margins indicate monopoly power with something Hemphill had written in his antitrust casebook for law students:

“In addition, the evidence itself will often be ambiguous. Consider profit rates. High returns might be attributable to rapidly growing demand for the industry’s product or, for a particular firm, superior production resources or managerial skill.”

The point of the questions was to establish that Hemphill hadn’t ruled out these other potential causes for Meta’s profit margins. Hansen also asked about whether Meta's apps are “two-sided platforms,” an antitrust concept that here implies users on one side and advertisers on the other side. We expect to cover two-sidedness in more detail with Meta’s experts. For now, it’s enough to remember that Hemphill didn’t attempt to study profits on the advertising side of the platform.

Hansen also prodded Hemphill on not having data on Meta’s U.S. profits. Hemphill said he used the data he had. Hemphill also said that to calculate economic profits, he would subtract the weighted average cost of capital from return on invested capital (“ROIC”), before Hansen pointed out that FTC expert Kevin Hearle’s calculations on economic profits used “internal rate of return” instead of ROIC. Hansen showed several demonstratives from defense expert economist Dennis Carlton. One showed that ad load did not materially vary by age cohort for those 35 and older; users aged 25-34 were shown fewer ads; and users 13-24 less than that, per the exhibit (although I didn’t catch if this was specific to a single Meta app or was across apps).

Hansen ended on more of a statement than a question, saying that Hemphill’s summation “tied together your preconceived idea that you convinced the FTC to bring that’s made you millions of dollars” and that he knew what he thought of this case before seeing “a shred of evidence.”

Redirect

On re-direct, the FTC’s Krisha Cerilli returned to documents to give Hemphill an opportunity to explain the context. One demonstrative showed that Facebook mobile ad load increased 3.1 times and revenues increased 8.1 times from 2014 to 2022:

Hemphill also gave his side of the “roadshow” story, where he referenced the law review article above, testifying that he and Wu had become “sufficiently familiar with some of the facts surrounding then-Facebook’s conduct that it seemed like something for enforcers to pay attention to.”

Had Hemphill formed a view at the time of the roadshow that the acquisitions were definitely anticompetitive? Answer: “No, no, no.” Hemphill wasn’t paid for that first meeting, either. And he said he wasn’t lobbying the FTC to bring an action in the intervening years before he was retained. After disclaiming that he had the 2025 data Carlton had for his demonstratives, Hemphill stepped down.

Day 19 ended with Tom Alison, Head of Facebook at Meta. For reasons of space, we’ll bring you that summary, along with Alex Schultz, in a future post.

Bonus

Hemphill’s direct slide presentation is PDX0090 at the exhibit site.

Interesting approach from Hansen in his impeachment of Hemphill. It seems based on how you phrased it, that it was effective in undermining his credibility.

However, it does beg the question, if in fact Hemphill HAD prejudged the outcome of the case, does that in any way reduce the substantive merit of his testimony based on evidence other than his own opinion? Of course it does call into question the validity of Hemphill’s opinion. But if Hemphill’s testimony is primarily his interpretation of factual evidence, isn’t it just as likely that his interpretation is correct or not correct, independent of his views on the case as a whole?

I’ll be interested to see if the judge’s opinion reflects this cross.

Incredible writing and coverage! Great job!

I always wonder why people say it's free and don't focus on the prices they charge advertisers. I thought the google ad tech trial was great when it came to that because you could see the anger of the people who actually do pay. I don't see why the FTC didn't bring and advertiser angle to the price side of things.

There's an obvious ad load tax, but it's like trying to prove tyson has a chicken monopoly by measuring the size of the pens they keep the chickens in.