What motivated Apple?

On Day 10, Apple executive Eddy Cue testified amidst increasing scrutiny of the trial's secrecy

When court resumed today for the start of the third week of the Google antitrust trial, we knew that Apple executive Eddy Cue would be taking the stand to testify about Apple’s longstanding agreement to make Google the default search engine on Apple devices.

One thing we didn’t know was how much of that testimony would be public.

In the end, we got somewhere between one hour and two hours of open-court testimony from Cue, who was on the stand for a little more than half the day — some of it in the morning on direct examination from the DOJ, and some of it in the afternoon on cross examination from Google.

That might not seem like a lot of public testimony from a key witness in the case, but Cue’s testimony came on the heels of his colleague John Giannandrea testifying almost entirely behind closed doors. It was also the morning after a flurry of late-night filings from the DOJ, Google, and Apple arguing over issues like the confidentiality of Cue’s testimony and the DOJ’s public posting of admitted exhibits.

So when the court officer announced just before 9:30 AM this morning that court would be starting in closed session, it felt questionable whether Cue’s testimony would be opened to the public at all.

It turned out that Cue didn’t take the stand during that initial closed session, which lasted about 45 minutes; when court re-opened, Judge Mehta said they had been addressing the parties’ filings on what portions of Cue’s testimony should be confidential. Cue was then called to the stand to begin his testimony in open court. Here’s my thread on X/Twitter summarizing Cue’s testimony from the morning:

https://twitter.com/BigTechOnTrial/status/170669977636279506

A couple of points to highlight from Cue’s morning testimony:

First, Cue’s testimony included a passing reference to the possibility of Apple creating its own search engine if it couldn’t come to an agreement with Google. The possibility of Apple developing its own general search engine has been reported on before — and presumably was the subject of closed-session testimony from both Giannandrea and Cue — but I believe this was the first time that it was mentioned in this trial during public testimony.

The DOJ didn’t probe this reference in open court,1 but it’s significant to the extent that DOJ can show the revenue share Apple received from Google caused it to stay out of the market of general search engines. Google can argue other existing search engines can’t compete with the quality of Google search, but a rival staying out of the market entirely would be a clear anticompetitive effect of Google’s default search engine agreements that is harder to argue against.

Second, the DOJ presented Cue with a slide that depicted the options iPhone users are prompted with when they open their Maps app for the first time. As I summarized in the thread above, Cue explained why this kind of choice is “completely” different from presenting users with a choice about what search engine to make their default. But later in Cue’s testimony, DOJ elicited from Cue that user search data is a component of user privacy, which Cue agreed was “absolutely” important to Apple.

The implied message that DOJ seemed to be trying to get across to Judge Mehta is that the default agreements are really about the money for Apple, and not privacy or user experience. If privacy was the main concern, Apple could prompt users to choose their default search engine when they first open Safari, just like users are prompted to choose their privacy settings when they first open Maps.

In the afternoon during its public cross examination of Cue, Google hit back hard against any notion that Google search doesn’t improve the quality of Apple devices.

This began with Cue emphasizing the priority Apple places on the “out-of-the-box” experience for customers, which means it never pre-loads any third-party apps on Apple devices and tries to limit the choices users are prompted with before being able to use their device. Cue explained that Apple does this partly because it is easy for users to download new apps or change their default settings. “If you know how to set your wifi, you know how to switch your search. . . . It’s not very complicated,” Cue said.

Cue also testified that users only have to switch their default search engine once: “Once you switch the default, it stays unless you decide to change it again.” This testimony from Cue contradicted prior testimony from DuckDuckGo CEO Gabriel Weinberg, who said: “If you switch some of these defaults eventually you’re just going to be switched back to Google if you do nothing.”

The overarching theme of Cue’s afternoon testimony was that Apple sets Google as the default search engine, because it provides the best experience for users. Google’s attorney bolstered this theme by presenting exhibits that showed Apple’s press releases announcing the development of its Safari browser in 2003 and of the first iPhone in 2007; both of these press releases touted Apple’s integration of Google search capabilities.

Bing enters the chat

Today, we also heard the first testimony from a Microsoft employee — Mikhail Parakhin. As CEO of Advertising and Web Services at Microsoft, Parakhin testified that he shares responsibility for investment decisions that Microsoft makes in search. Parakhin is also a unique witness because he’s worked at high levels of two of Google’s competitors; before starting his current role at Microsoft, he worked as the CTO of Yandex, Google’s main competitor in Russia.

Thus far, much of Parakhin’s testimony has been focused on explaining the “feedback mechanisms” that are driven by Google search’s relative scale advantage over Microsoft Bing.

The primary feedback loop was summarized on a slide in an exhibit introduced by the DOJ: More users → More advertisers → More data → Better search and more relevant ads → More revenue to invest in development and distributions. Parakhin explained that all of this leads back to more users and the feedback loop continues.

He also mentioned “less obvious” ways in which Google’s relative scale advantage allows it to enjoy positive feedback loops. As an example, he said that it takes restaurants and businesses about the same amount of effort to correct errors in their hours of operation that appear on Google or Bing. But since Google has much higher user traffic, restaurants and businesses are more likely to take the time to update their hours of operation on Google, rather than Bing or another search engine. These corrections improve the quality of Google over other search engines.

All of Parakhin’s testimony so far has been public and Google hasn’t yet begun its cross examination of him — so we’ll get to hear more from Parakhin tomorrow.

The Trial’s “Unprecedented Secrecy”

After a week in which I estimated that the majority of testimony was sealed — including the entirety of testimony on Friday — the trial’s lengthy and frequent closures to the public have started to attract some broader media coverage.

This morning, the New York Times published an article titled: ‘Unprecedented’ Secrecy in Google Trial as Tech Giants Push to Limit Disclosures. The New York Times article was published within a few hours of this article from The American Prospect (“Google Erects Cone of Silence Around Antitrust Case”) and this podcast from Marketplace (“What’s happening in the Google antitrust trial? It’s kind of a black box.”).

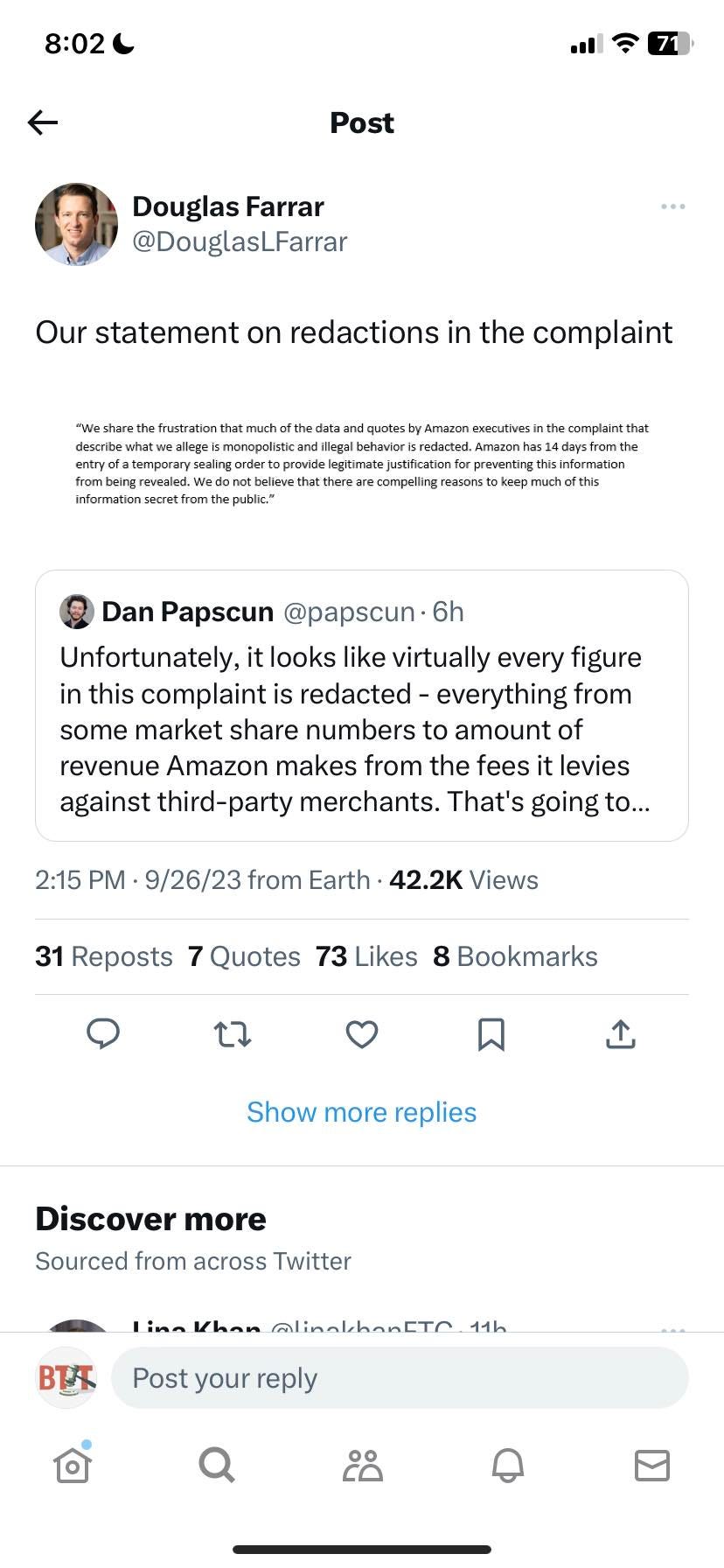

This issue doesn’t seem likely to be going away anytime soon — especially because it has already surfaced as an issue in the FTC’s lawsuit against Amazon.

At the end of court today, though, we got some signals that public access to this trial may be starting to improve.

Namely, Judge Mehta resolved what to do about the DOJ publicly posting admitted exhibits. This issue came to light in a dramatic moment last Tuesday and remained a source of disagreement between the parties throughout the week. Last night, Google and DOJ filed a joint status report, which highlighted that the parties’ main disagreement was on how long Google would get to review exhibits for confidentiality issues before DOJ posted them online.

Judge Mehta ruled that Google and any other impacted third parties would get a three-hour window after DOJ provided them with copies of the exhibits they would like to post at the end of each trial day. So if all parties act promptly, we should expect to see DOJ posting admitted exhibits nightly around 8 or 9 PM ET. Judge Mehta also said that if Google or a third-party raises an issue that DOJ doesn’t agree with, DOJ should refrain from posting until they can work out the disagreement in court the next day.

This end-of-day discussion also included an interesting exchange Judge Mehta had with DOJ’s lawyer about DOJ’s opposition to Google’s attempts to seal portions of the trial. I don’t have great notes on this, but the gist seemed to be that Judge Mehta wants DOJ to speak up if they believe the public interest demands open-court testimony. This came right after DOJ’s lawyer disputed Apple’s filing, which said that DOJ “unilaterally chose to close the courtroom” for all of Giannandrea’s Friday testimony.

Judge Mehta is normally soft-spoken, but it felt like he was speaking pretty forcefully during this exchange. I’ll try to provide an update on exactly what Judge Mehta said after I’m able to review a transcript.

One other note from this discussion: Judge Mehta provided a public correction, commenting that contrary to some reporting, he never ordered DOJ to take down the exhibits it had already posted. Since it seems like everyone is trying to clarify the record, I’ll add my own clarification: I’ve seen a couple of articles cite Big Tech on Trial as reporting that Judge Mehta ordered DOJ to take down the exhibits, but I never reported that. Here’s my original X/Twitter thread on what happened.

That’s all for today. I’ll be back in court tomorrow to follow the action.

Update (9/27): I got the transcript, so here’s exactly what Judge Mehta said at the end of the day about the DOJ objecting to closed sessions.

“Well, let me state what I stated earlier today in closed session, which is as the presiding judge in this case, I don’t have a crystal ball to know what’s coming up. So it is very difficult for me to predict and say, well, this ought to be in closed session and this ought to be in open session. So I’m replying largely on the plaintiffs, who represent the public interest, to let me know if you think it is objectionable to go into closed sessions. So this idea that you are not objecting, I get it, that’s your official position. But only if you object does it get teed up for me to consider, because they don’t care….Actually, that’s too strong. But they don’t have the same interests you do.”

Once again, I would presume that the DOJ didn’t probe it in open court because they have been instructed to reserve such questions for closed sessions.

Mehta split the difference between the parties' proposals on exhibit posting a bit more favorably to the public than I might have expected given his choices thus far, so it seems like your work and other news reporting has made him think more about public perception.

Thank you for your continued commitment to reporting this trial. Please keep focused on the fact of so many closed sessions. You are doing great work!