It's Groundhog Day for a Google Breakup

Deliberations on the remedy to Google's Ad Tech monopoly start today. Will Judge Brinkema deliver Google the break-up it evaded in Search?

The remedy phase of Google’s Ad Tech monopoly trial begins today. Google was found liable last April for illegally monopolizing two markets related to open web digital advertising technology. The trial starting today before Judge Leonie Brinkema in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia will decide what remedies the court will impose to try to repair the market from Google’s damage.

First, let me introduce myself. My name is Jerry Cayford, and I am a philosopher who has some training in economics and a strong amateur enthusiasm for the law. It may seem odd for Big Tech on Trial to assign a philosopher to cover an antitrust trial. But I believe (with no bias at all) that this is entirely sensible. The Google Ad Tech remedy trial is a very big deal, and philosophy is, after all, the discipline that tries to give us the big picture. There is a bit of philosopher in all of us, a drive when we see important things happening to get a handle on what they mean overall, and where they’re taking us. I’m going to try to help you do that for the two or three weeks that this remedy trial will last. As usual with BTOT, I’ll also be providing color to the daily details, and as always, this is a two-way platform, so subscribe and leave comments below.

How We Got Here: The “Rocket Docket” In Action

It’s been a while since we’ve reported on the Google Ad Tech trial. In the intervening year, BTOT has covered a whole separate trial, the Federal Trade Commission’s monopolization case against Meta (Facebook/Instagram). And starting this month, a separate federal court under the tutelage of Judge Amit Mehta delivered a remedy in the Google Search monopoly case that has attracted round and swift rebuke, including by this publication (“A Judge Let’s Google Get Away With Monopoly.”)

So you can be forgiven for forgetting the details of this case, which the Department of Justice and eight states first filed against Google in January 2023 for illegally monopolizing various digital advertising markets. (Nine more states would eventually join the suit, bringing the total number of Plaintiff states to a bipartisan group of 17.) Meanwhile, the State of Texas filed its own litigation back in December 2020. To give you a sense of why they call the Eastern District of Virginia the “rocket docket,” a trial in the Texas case, filed in 2020, is now on hold pending resolution of the proceedings we’ll be covering here, which were initiated in 2023.

The underlying trial in this Google Ad Tech case took place in September a year ago, and you can review all of BTOT’s daily coverage in the archive. Judge Brinkema issued her opinion in April of this year. Again, this is fast for a complex trial, which bears some relevance to the project before the court: the two sides will be arguing in the coming weeks about the significance (or not) of fast-moving technological changes that have occurred between the time of Google’s illegal actions and today (or whenever the remedies will be in place). One purpose of an antitrust remedy is to unfetter the market so that competition may flourish, which is a forward-looking mandate, and slow-moving courts can hobble themselves in the face of fast-moving technologies. Google will attempt to use this to its advantage, citing a “rapidly changing technology ecosystem” to push back on the DOJ’s requested divestiture remedy. The DOJ is likely hoping that Judge Brinkema will do justice to the “rocket docket” and avoid the pitfalls that hobbled her counterpart in the Google Search case.

The Monopolized Markets: the Plumbing of Open-Web Digital Advertising

Judge Brinkema’s two main findings were that Google engaged in activities to illegally acquire or maintain monopolies in two markets related to the display of digital ads on the “open web”: (1) the publisher ad server market, and (2) the ad exchange market. That’s a mouthful, and I’m going to give you a primer on what these two markets are, both because they’re pretty interesting and because you’ll find it much easier to follow the action later if you have a solid grasp on these new and strange technologies at the heart of the case. Longtime followers will find this a cursory review of our earlier deep-dives.

The first key point is that we are not really talking about the market for advertising per se, but rather the software underneath modern digital advertising—the “plumbing,” so to speak, or the infrastructure that makes internet advertising work. Our intuitive picture—our old and obsolete picture—comes from something like billboards: the billboard owners look for advertisers (“This space available”), and advertisers meet them at the office to negotiate a price and sign a contract. Early on, internet advertising did work like that. A website willing to host advertising (a “publisher”) sought companies looking to advertise on websites, and real people met in physical offices in human time to sign paper contracts. A certain ad would automatically go up on a certain website for the length of the contract. Fast forward. There are now thousands or millions of websites and advertisers, and everyone now knows that the effectiveness of advertising varies hugely by who exactly is seeing it. Finely targeting ads to viewers is far more valuable than generically broadcasting a message, and it’s a key part of the value that Google offers—and hobbles through its dominance.

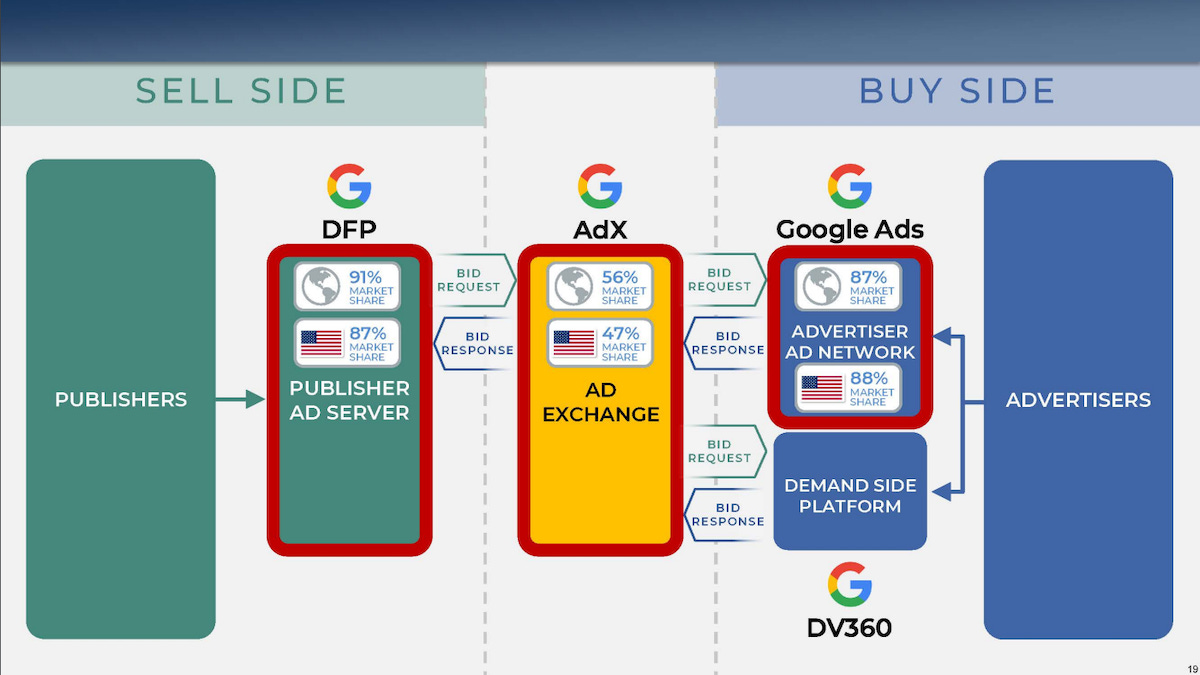

The underlying structure of targeted internet advertising is completely different from the old days. Instead of individual websites selling ad space, they hire a service to manage their space for them. This is a “publisher ad server,” and it has a large inventory of websites looking to sell space, which is why we’ll call it the “sell side” for short. On the “buy side” is an “advertiser ad network,” which similarly has a large inventory of advertisers looking for space to post ads. (Judge Brinkema found Google not liable for illegally monopolizing the buy side.) In between the publisher ad server (the sell side) and the advertiser ad network (the buy side) is an “advertising exchange” which matches up ads with spaces by holding a lightning speed auction. In the time it takes a website to load after you click on it (maybe half a second), an ad exchange auctions off the advertising space on that webpage to the highest bidder among all the advertisers in the ad network inventories. The three parts together are known as the “ad tech stack.” Companies compete to provide these services on the sell side, ad exchange, and buy side, and these are the three markets Google dominates with DFP, AdX, and Google Ads, respectively. Here’s what that all looks like visually:

Now that you understand that internet ads are placed through auctions among managers of inventories of ads and ad spaces, you can imagine the sorts of shenanigans that could help a dominant player illegally maintain its monopoly. Google engaged in many of them. The most important was “tying” its publisher ad server, DoubleClick for Publishers (DFP), to its ad exchange (AdX), meaning publishers couldn’t use the AdX exchange (to access advertisers) unless they listed their ad space with DFP. AdX and DFP, both already dominant, could then reinforce each other through “a series of acts that diminished rivals’ scale, thwarted their ability to compete, and harmed customers,” to quote Judge Brinkema’s opinion. It is quite readable, if you want to go straight to the source. I will not detail the shenanigans here, but they include giving AdX a “first look” at any spaces listed with DFP, giving AdX a “last look” at bids so it could adjust to win, and forcing publishers to set the same “floor” (or lowest acceptable price) for AdX as they set for other exchanges—which was key to thwarting “header bidding,” which was an attempt by other players to get around Google’s bottlenecks.

All of this has immense implications for the flow of information across the internet. And it has proven immensely profitable for Google—to the tune of hundreds of billions of dollars per year, which Google has redirected to fund all sorts of things that are “free” to consumers, including Google Search, Gmail, and YouTube. But the underlying trial revealed that Google’s revenue is based on monopoly fees (“Google Knows Its Ad Exchange Isn't Worth its 20% Fee, but Refuses to Lower It.”) And Google’s domination of open web display advertising is part of the story behind the near-extinction level crisis facing web publishers, including journalists whose prior direct relationships with advertisers is now intermediated by Google’s monopoly exchange. As Google’s “free” services are funded by monopoly fees, traditional media is disappearing behind paywalls - or disappearing altogether. Traditional media traditionally funded itself with advertising. It still does, to a large degree. As Google (and other tech giants) have taken a larger share of advertising revenues—in Google’s case, via a host of illegal conduct—other organizations that depend on that ad revenue have diminished.

Which brings me to one other point of clarification: this case concerns markets related to “open-web display ads.” These are ads that are being placed on websites on the open internet, as opposed to ads placed in closed ecosystems like Facebook, TikTok, or Amazon, which are in-app “walled gardens.” Open-web display ads are only part of the broader digital advertising ecosystem, and an under-current of these proceedings is that Google has played a sizeable role in killing the market for open-web display ads by siphoning funds that used to go directly to publishers, including journalists and other website operators. Google will argue in these remedies proceedings that any effort to terminate its various monopolies within the broader market for open-web display ads will hinder its ability to compete against the siloed walled gardens maintained by Meta, TikTok, Amazon and others. But should Google be able to evade a complete remedy to its illegal monopolies in this case by arguing that competition has expanded beyond a market that it has played a central role in diminishing? That will be a major area of dispute in the weeks ahead.

Should Google (Finally) be Broken Up?

To no one’s surprise, the two sides are far apart in what they have proposed the court should do. Both sides have focused heavily in their presentations to the judge on one issue: divestiture. The DOJ lays out its preferred remedy in its Proposed Final Judgment, where it proposes that Google should have to divest its advertising exchange, AdX, and at least the Final Auction Logic part of its publisher ad server, DFP. It argues that these divestitures are necessary to eliminate Google’s monopoly, restore competition, and prevent further monopolization by Google in the future. But what the DOJ characterizes as “the touchstone of an antitrust remedy,” Google characterizes instead as “radical,” “extreme,” and “severe.” Google unsurprisingly argues that behavioral, not structural, remedies are all that’s needed to guarantee its future honesty, and there is no precedent for forced divestiture (except in cases where illegal acquisitions created the monopoly).

We will hear a lot this week about which legal precedents apply and what they say. A couple of points jump out from the two sides’ proposals. Perhaps most noticeable is Google’s repeated citation of the recent remedy for its illegal monopolization of online search. Its second most cited case is US v. Microsoft, the last major big tech case that made headlines a quarter century ago. These two make up the large majority of its citations of previous cases. And yet, the recent Search decision is only a district court judgment (and not the Eastern District of Virginia, either). The Search case also dealt with an almost completely distinct set of facts, so any attempt to draw inferences about this case from the outcome of Search is an apples and oranges comparison. The Microsoft case went to the DC Appeals Court (which does not cover Virginia), but not to the Supreme Court. The cases Google cites, then, are far from controlling in this Virginia court. The DOJ’s citations are heavily to Supreme Court decisions. Some of those precedents, though, are considerably older. Given Judge Brinkema’s candor during the liability phase of the trial, I expect we will see rather soon how she might resolve the parties’ discordant reliance on binding and persuasive legal precedent.

A side event worth noting concerns the wider world’s view of this case. One of the questions Judge Brinkema had to settle at trial was the geographic scope of the pertinent advertising market. Google argued it should be the US, and DOJ argued it should be the whole world (with caveats). She sided with DOJ for the wider world market. Just a few weeks ago, a part of this wider market, the European Union, judged Google liable for this same monopolizing behavior in the advertising technology market. The EU fined Google $3.5 billion and left open the decision on divestiture, making clear it is a serious possibility: “only the divestment by Google of part of its services would address the situation of inherent conflicts of interest,” said the EU Commission in a press release.

With that, my next report will cover the parties’ opening arguments and probably the first few witnesses. I’m excited to be with you for the next weeks! We get to watch how Judge Brinkema—along with teams of lawyers and witnesses on either side—untangles a swarm of interconnected issues, while keeping an eye on the vast implications of this critical case.

Thanks for the recap! I always look forward to reading Big Tech On Trial, but I will admit the details have faded over the last year. Fingers crossed for a Google breakup!

Great recap on the underlying principles of this case!