A Judge Lets Google Get Away with Monopoly

Judge Amit Mehta had a chance to restore some semblance of the rule of law when he handed down a remedy decision in the Google case. He didn't. Google won this round. And Wall Street is rejoicing.

This piece is cross-posted at the BIG Newsletter.

The rule of law is on tenuous grounds in America these days, with even easy stuff that might hinder the powerful running into serious obstacles. Yesterday, the decade-long campaign to stop big tech from dominating our society took a significant step backwards, as the judge hearing the search case against Google, Amit Mehta, chose not to meaningfully constrain the firm’s illegal behavior. And to engage in such deferential behavior, he openly ignored Supreme Court precedent.

You don’t have to take it from me. It’s Mehta who last year found Google to have violated the law. “Google is a monopolist,” he wrote, “and it has acted as one to maintain its monopoly. It has violated Section 2 of the Sherman Act." It’s also Mehta who found the Supreme Court mandated what he called the “remedial objective” in monopolization cases, to “terminate the illegal monopoly.” But, Mehta wrote, “remedies designed to eliminate the defendant’s monopoly—i.e., structural remedies—are inappropriate in this case.”

So there we go. Mehta understood the law mandates he terminate Google’s monopoly, but he just decided against doing so. This kind of lawlessness, incoherence and deference to big business is now routine among elites in our society, so I guess it’s not too surprising that it happened in this case. In fact it’s not surprising to readers of BIG; back in June I wrote a very timely piece on precisely this dynamic, titled “Why Is Google Still in One Piece? The Terminating a Monopoly Problem.” In it, I described why Mehta may turn his back on this requirement and flout the law. I had hoped he wouldn’t, but he has.

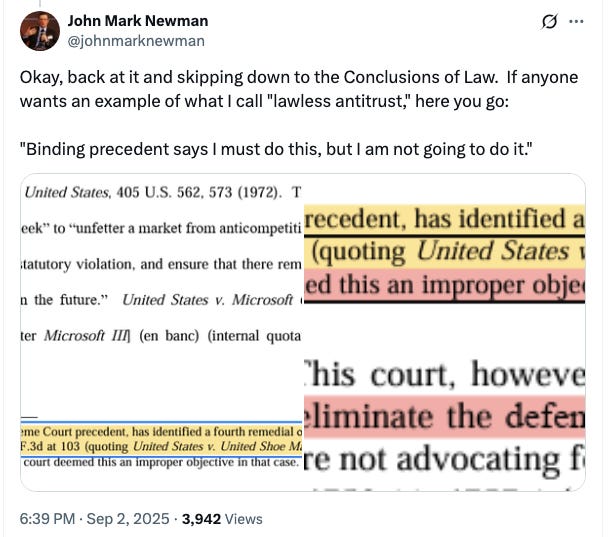

Here’s law professor and former enforcer John Newman making the same point.

So what’s Mehta’s actual remedy? To understand that, we have look at the root of Google’s monopoly, as Mehta saw it. I characterized the case as follows, that the search giant had “bought up all the shelf space for search engines, aka paid Apple and browsers like Mozilla to be the default search provider instead of any of its rivals. It created Chrome so it could control that channel of distribution, and it bought Android for the same reason.” The goal of the remedy that the Antitrust Division sought was to terminate that monopoly, confiscate the fruits of its illegal behavior, and make sure monopolization would not recur. Here’s what I noted the DOJ sought:

The DOJ asked to remove the defaults that automatically place Google as the search choice for most browsers, an end to search-related payments, a spinoff of the Chrome browser which was itself a big search access point, as well as regulation of the mobile operating system Android. It also asked for syndication of Google’s search results and data to approved rivals, which is a way of forcing Google to not enjoy the illegal “fruits” of its monopoly by offering rivals some access to the secret sauce.

There were other requests, but those were the big ones. So what did the judge do? Mehta rejected both a Chrome spinoff and regulation of Android, since that’s a structural separation and he got nervous about that. But more insanely, he didn’t even say that Google had to stop paying Apple $20B+ a year to be the default search engine, it just had to limit such default payment agreements to one year terms. Mehta found that Google was doing illegal things to maintain its monopoly, but he didn’t force the company to stop doing those illegal things.

Why not? Well, he said that new companies like OpenAI had emerged to potentially challenge Google, and he didn’t want to, and I’m not kidding, hinder Google’s ability to compete with them. (“It also weighs in favor of “caution” before disadvantaging Google in this highly competitive space.”).

Beyond that, Mehta wrote that “cutting off payments from Google almost certainly will impose substantial—in some cases, crippling— downstream harms to distribution partners, related markets, and consumers, which counsels against a broad payment ban.” Here he’s talking about… Apple. Yes there are others, but Mehta could have blocked the contract with Apple, and let the other payments continue. But he didn’t. Mehta even wrote that if he restores competition in search, it could hurt Apple’s ability to invest in making phones better. It is quite problematic for a judge to refuse to break an illegal monopoly on the premise that an adjacent non-relevant market might be harmed. I can’t emphasize how crazy that is, it’s like, as my colleague Nidhi Hegde stated, finding someone guilty for bank robbery and then sentencing him to write a thank you note.

Mehta also rejected the smaller remedies. He said no to choice screens, and advertiser data access. There was no remedy for publishers who are victimized by being forced to allow Google to train on their content in order to appear in search. That free press crushed by Google’s bad behavior, well, they will now be further wrecked by Google’s AI Now summaries on its search page, without any resource. Mehta even declined to impose an anti-retaliation or self-preferencing ban.

So what did Mehta impose? His remedy was to bar Google for six years from entering exclusive contracts for distribution of search, Chrome, Google Assistant or its Gemini app. Google can’t condition Play store licenses on distribution agreements, or prohibit partners from distributing rival search engines, browsers, or generative AI products. He also mandated sharing of some search index and user-interaction data to “qualified competitors,” and “search and search text ads syndication services” that Google can price however it chooses. Some of that is fine, perhaps it will help some of the generative AI firms who have access to the capital markets. Here’s former Antitrust chief Jonathan Kanter saying that.

But I don’t buy it. The last meaningful reference point for an antitrust remedy is the Microsoft case. In that one, the break-up was overturned, and a weak interoperability mandate was imposed. But the real penalty to Microsoft was embarrassment and fear within the executive suite; no longer would the company crush its rivals, from then on, lawyers would cautiously oversee product design. That’s not ideal, Microsoft should have just been broken up and set free to compete. But a chastened leadership did have the effect of not killing the next generation of companies, who ended up creating Web 2.0. That’s deterrence, which is one goal of antitrust remedies.

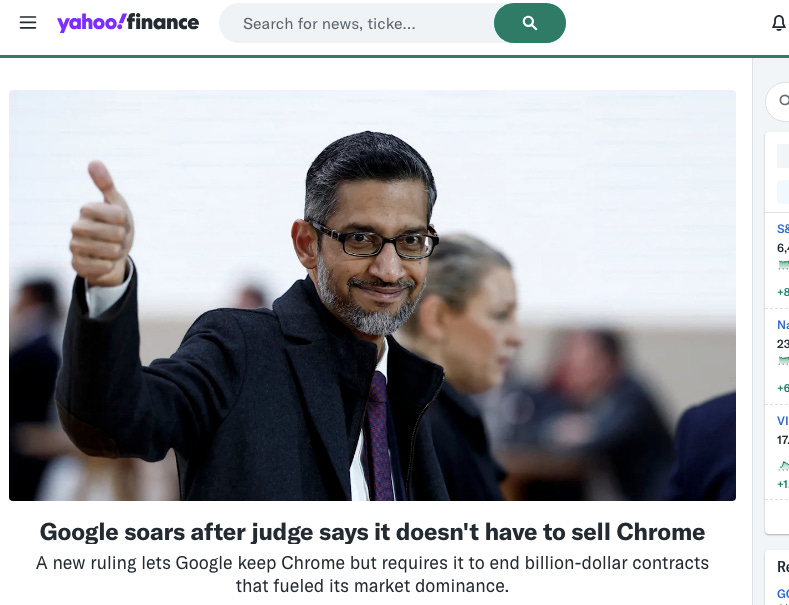

This remedy, by contrast, is obviously going to fail. And the main reason is that, unlike Microsoft, Google’s leadership is utterly unchastened. Google CEO Sundar Pichai and chief legal officer Kent Walker will get bonuses for what they did. They see this conflict as one in which they fought bitterly, and kept at it, and shredded documents, and the result was… victory. They will have no compunction continuing to engage in unlawful behavior. After all, what’s the worst that could happen? Would a rival or the government really go before a weak judge who doesn’t want conflict, and convince him to act? I don’t think so. In other words, this decision isn’t just bad, it’s virtually a statement that crime pays.

There are also the technical reasons that, even if Google does adhere to the remedy, it won’t work. As Newman put it, “Google apparently remains free to pay smartphone OEMs & browsers for preloading + prime placement of Search. Without more, that's a ready-made recipe for ongoing monopoly.” Antitrust expert Tim Wu also found the remedy bizarre.

Senator Amy Klobuchar seemed unhappy, and DuckDuckGo put out a blistering statement.

I suppose these moves are, for Mehta, intended to “pry open” the market for search services, but both Google and Apple shares soared, as investors realized that the judge protected the existing monopolistic arrangement. Google itself put out a blog post lightly praising the judge, which is a red flag, since the judge found the company to be a lawbreaker.

At any rate, if you want a few silver linings, here they are. First, this remedy is almost as weak as it could be, so maybe there will be an incentive to do a cross-appeal. Google is going to appeal, because it wants to have the original monopolization finding overturned. But AAG Gail Slater and Colorado State AG Phil Weiser both are making mild noises about a possible cross-appeal of the weak remedy, saying publicly they wonder whether Mehta’s solution “goes far enough.” Since there are many errors of law in Mehta’s decision, such a cross-appeal might work. Second, there are other Google antitrust losses. A new hearing starts in three weeks in Virginia, where a more assertive judge is overseeing an adtech remedy phase.

So there we go.