The Stakes of the Third Google Antitrust Trial

A new antitrust trial against Google begins today, this one over control of ad technology and publisher revenue. The question here is as follows. Who killed the free press?

Welcome to the first issue of Big Tech on Trial’s coverage of the Google adtech antitrust case. This case will be covered by Tom Blakely.

Hi there! It’s been a big year for Big Tech going on trial. And it’s about to get a whole lot bigger.

Today, the Department of Justice and a score of states start their trial squaring off against Google in the Eastern District of Virginia in a heavyweight antitrust bout concerning the tech giant’s alleged monopolization of advertising revenue. Advertising, while rarely popular, is the lifeblood of something older than American democracy – newspapers.

In 1831, Alexis de Tocqueville noted something unique about our democratic society. “In America there is scarcely a hamlet which has not its own newspaper,” he wrote. There were so many with such a diversity of opinion that the wealthy and powerful were afraid to “thus deprived of the most powerful instrument which they can use to excite the passions of the multitude to their own advantage.” And such papers were financed by advertising, which shielded publishers from the state.

Today, however, two thousand out of three thousand American counties have no local newspaper. Why? Well, that’s what this case is about. Is Google’s division that serves publishers, which has about $20 billion of revenue, a mechanism for making advertising more effective? Or is it a method of extraction?

Those are the key questions, and the stakes.

And Google is coming as a massively powerful and wealthy giant, but a limping one. This case comes on the heels of last year’s landmark trial against Google’s search business, a historic defeat for the tech giant, with Judge Amit Mehta finding the company acted illegally to maintain a monopoly in general search and search ads—its now notorious king’s ransom to the tune of $20 billion of dollars paid each year to Apple to be locked in as the default search engine on the company’s devices.

Here though, a different scheme is at play, one that is more complex and technical, which is in essence the creation of a financial marketplace to structure ad buying and selling. The Justice Department’s complaint, some 140 pages in length, lays out the government’s story of how the systems responsible for showing you online display ads on the internet came to be.

Most of us don’t spend much time thinking about ads, because they are annoying. But online display advertising – a certain kind of online ad that finances a good deal of publishing - is an economic behemoth. A subsidiary of Google called ‘Google Network’ has come to capture much of this business, roughly $20 billion in revenue every year in America —getting the ads from sponsors, placing the content, selling to the highest bidder, and to your eyeballs, all in fractions of a second—is equally massive, sophisticated, and according to the government—an illegal monopoly.

But before we go further, an introduction. My name is Tom Blakely. I’m an attorney from Boston, and I pursued a legal career in large part due to my experience as a media entrepreneur having to deal with the power of big tech, and the legal questions that surround the industry. In my (young) career I’ve made stops in the Department of Justice, Big Law, worked with legislators on statutory construction, and in a number of other fun places. As a first-generation college and law school graduate, I came into this world from the outside. It was always clear to me how issues of concentrated power, in this case concentrated corporate power, play such a profound and driving role in our society. My generation—younger millennials and older Gen Z-ers—came of age at exactly the right time to see Big Tech dominate large swaths of our social order.

Ok, let’s go on to the case.

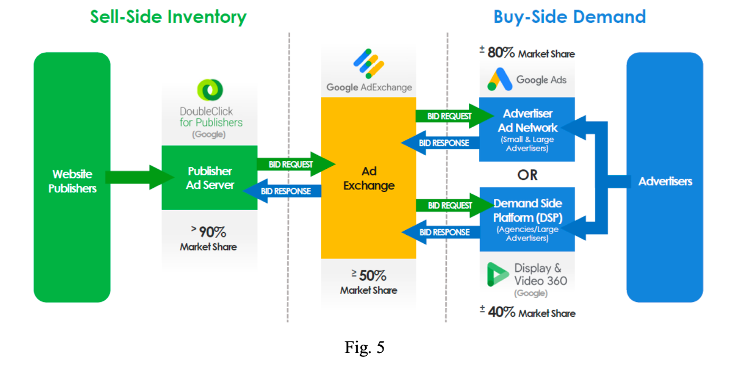

Both the government and Google agree on basic facts. First, from the early 2000s onward, Google has built a financial marketplace for ad buyers and publishers to match with each other, and today it serves roughly 5 trillion impressions a year and 13 billion a day on the open web. This line of business is known as Google Network. It constructed this division via a host of acquisitions, mostly prominently that of DoubleClick in 2008, but continuing for a decade and a half with other purchases. Second, many if not most publishers use Google’s software to manage their online display advertising inventory, and many advertisers use Google’s software to plan and run advertising campaigns. They match on Google’s exchange. Third, Google gains access to much the user and ad data of its publisher and ad clients operate running its software, which it uses to perfect ad targeting. Fourth, Google owns and operates large amounts of content itself, from Gmail to YouTube to Search, on which it also sells ads, competing with its publisher customers.

In other words, you have publishers (websites and content creators that attract an audience) and advertisers (think of big companies like McDonalds and Nike that want to advertise their offerings to those audiences) sitting on each side of an equation. To make this ecosystem work, a sophisticated array of software is needed to instantly collect demographic information about a viewer, find the ad in Google’s massive ad inventory that can be shown to that viewer for the highest price, place the ad, show it to a viewer, and so on and so on.

So what’s wrong with this picture? What the government alleges is twofold. First, many of these acquisitions were illegal attempts to build a monopoly. Second, Google’s tactics as it built its control over the purchase, sale, and exchange of advertising were designed to block rivals from competing by tying its products to one another. As the DOJ put it in the complaint, "If publishers wanted access to exclusive Google Ads’ advertising demand, they had to use Google’s publisher ad server (DFP) and ad exchange (AdX), rather than equivalent tools offered by Google’s rivals." The result is that Google has been able to charge very high prices for its services, between 30-50% of every dollar spent on advertising. A comparable network like VISA or Mastercard charges something like 2-3%.

Because Google has such a powerful hand in every step of the ad tech industry, goes the argument, it alone has the power to use and deploy hidden levers to manipulate the overall system to its advantage. Figures such as the following are strewn throughout the complaint—sketching the Rube Goldberg machine of digital advertising dominance that Google has assembled in the last twenty years.

Only with such sweeping control over the entire, largely opaque ecosystem—Google is free to turn levers to extract high prices from its captive customers, or potentially direct ad revenue away from its publisher clients and to its own properties entirely.

Typically, when talking about monopolies we are concerned with vertical or horizontal integration, market concentration, pricing power, the market definition, and the like. Here though, the concern is much larger, and in some ways, simpler to observe—that Google essentially controls an entire industry, all of its constituent parts, its infrastructure, its laws of economics—everything.

What Google did reminds me of the story of how Robert Kraft came to acquire the New England Patriots in the 1990s. He bought the surrounding lots next to the stadium, and then the land that the stadium sat on, with restrictive covenants that made the team (which he did not yet own) have to play there until at least 2002, and deal with him in the event of a sale of the club. When the team’s former owner wanted out, Kraft had significant leverage, eventually effecting a hostile takeover of the only thing he did not yet own—the football team itself.

Sticking with the football analogy, it would be as if the NFL controlled the NCAA, represented every player, also represented every NFL team in every negotiation, set every salary, told everyone how much they would pay or be paid, and how much would be paid to it, and so forth and so on. Basically, there are conflicts of interest in Google sitting on every side of the transaction. The government found that one Google advertising executive once asked the question, “[I]s there a deeper issue with us owning the platform, the exchange, and a huge network? The analogy would be if Goldman or Citibank owned the NYSE.”

In some ways, like a Georges Seurat painting, the government’s case against Google is more easily recognized by taking a few steps back and thinking simply of the big picture—a massive plumbing system of surveillance capitalism, financial engineering, and media, the moving parts of which are all entirely controlled by one firm, and one firm alone, that only answers to itself.

What is Google’s response?

“Success is not illegal,” Google argues in the opening of its answer, citing a line from a different but related monopoly case, Epic Games. v. Apple—a case that Apple lost in part and won in part. Google is just very good at what it does, and it would be bad policy to stop corporations who are good at producing things from doing so.

A few sentences later, Google argues that it has a lot of competition with this phrasing - “…many large companies that Google competes with every single day…”—a sort of holdover framing that it is still a scrappy garage startups scratching for every inch. It’s not an outlandish claim to say it’s not a monopoly in this particular market. You can buy online advertising on Amazon, TikTok, Snap, Meta – all over the place. How and whether Google dominates this particular will come down to something called market definition, which I’ll get to in a later post. (And which BTOT touched on repeatedly during the first trial we covered.)

Then there is the judge, the Hon. Leonie Brinkema, a Bill Clinton appointee. Matt Stoller was in the courtroom a week and a half ago, and he characterized her to me as a sharp, confident, no-nonsense presence, who was in no way impressed by Google’s retinue of lawyers. It was a hearing over a corporate policy to auto-delete chat messages, the so-called ‘Walker Memo;’ Brinkema was very unhappy with Google, claiming a bunch of evidence was ‘likely destroyed,’ and said she would not be particularly trusting of Google witnesses going forward. Brinkema also seems to have a good sense of the purpose of antitrust law, stating last year in ruling against Google’s attempt to have the case dismissed the following.

“The essence of antitrust law is to try to keep – you know, nothing is static, to try to keep the system working by recognizing that, at certain points, some companies may get too big for their own good, they’re self-imploding, or the technology may become so dominant that it’s just crushing all other elements where there can be innovation.”

Procedurally, the court is in the Eastern District of Virginia, known as the ‘rocket docket,’ because these cases are run extremely quickly. It was brought just a little over a year ago, and the whole thing could be done next year, at which point it will be appealed. That’s a shockingly quick turnaround for restructuring an industry.

Ok, so all that said, let’s go to the journalism 101 question: why does this case matter? And that brings me back full circle. Digital advertising is the bloodstream of the internet, and in many ways—of this country.

Advertising finances publishing, with everyone from independent content creators to legacy media outlets and newspapers living and dying with Google’s turn of its levers. Look to changes in algorithms to see how quickly publishers and creators can die at the hands of Google. For instance, the Wall Street Journal once refused to let the search giant give free access for its articles, and Google cut off 44% of its traffic.

If the government prevails and Google’s dominion over its Pottersville of advertising is diminished, we can expect publishers and advertisers to get revenue shares more favorable to them. The free press will live.

A government victory would represent a massive beachhead, another open breach, in the four-decade run of consensus pro-corporate antitrust policy in Washington, to go alongside a number of other sea change victories in recent years. It would inspire judges to be more skeptical of corporate power, willing to embrace antimonopoly arguments, and embolden antitrust enforcers, private litigants, legislators, and class action lawyers to attack corporate power with more hope of success. Google itself would probably be split up.

A Google victory on the other hand would be a sign of just how difficult it is to overcome what is a largely antitrust-skeptical judiciary. If a level of nearly complete control of an industry like this is not found to be a monopoly, many in the antitrust crowd may throw up their hands and wonder what is.

Well, that’s all for now. Of course, this will be yet another one of these trials with no audio stream, with no electronics allowed in the courtroom, per the policies of the Eastern District of Virginia. Judge Brinkema just recently denied the requests of the New York Times and other publications to allow reporters to bring merely electronics with them needed for reporting, even to be kept in a separate room. This of course makes it much more difficult to report on the case, makes it harder for the government’s zingers and smoking guns to be heard by the public, and helps Google keep what is done in the dark, firmly in the dark.

We hope to be able to shine a light in there.

Excellent explanation of how this works, and why it is so important. I worked for a state law school for 15 years and many students were like you - first in family, for some from high school grad to law school grad. They were the idealists who wanted change and like you learned the reality if their choices in their first few years. I kept asking what happened to anti-trust and monopoly law and fingers pointed at the government and judiciary. I’m so inspired to see the younger generation taking in one of the most important stands for equality and free speech.

Excellent first article.

What is the judicial rationale for refusing to allow audio streams or recording devices?