"Groomer"-Gate Revisited: Trial Exhibit Reveals More Details About Instagram's Disturbing Algorithms

A trial exhibit discussing Instagram's potential recommending of minors to "groomers" takes on a life of its own. A deeper dive answers some questions while raising others.

Discovery in antitrust cases—the production of documents, depositions of witnesses, and reports prepared by experts—is sprawling. Most business disputes are narrow: a buyer and a seller of widgets claiming a breach of contract, or a small group of patents alleged to be infringed. But antitrust cases can involve all of a company’s operations, over its lifespan. And that’s just the tip of the iceberg. Discovery from third parties is perhaps even more important in a monopolization case.

The discovery effort doesn’t just reconstruct the facts of a particular dispute, but the facts of an entire industry, sometimes over a decade or more. For those reasons, then, antitrust cases are an opportunity to peek under the hood and learn a bunch of things that might have only tangential relevance to the competition claims. Those things can take on a life of their own and become newsworthy in their own right.

And that’s what happened during Week 4 of the FTC v. Meta Platforms antitrust trial. As Bloomberg, MLex, and this blog reported, there was an exhibit that appeared to have troubling bullet points about child “groomers” trying to connect with minors on Instagram. But one of the slides we saw was redacted, and, at the time we went to publication, the exhibit was not yet available in the online repository of exhibits, which don’t get uploaded for two days after they’re shown in court.

Now that we’ve had a chance to review this full exhibit, there are some new, potentially important details to share that the FTC’s examination skipped over. Likewise, independent journalist Matt Taibbi’s Racket News quoted our coverage and included a fuller response from Meta about this exhibit that we’re posting here.

Because of the gravity of the topic, and what Chief Judge Boasberg called its “ancillary” role in trial, we’re highlighting the new discoveries for you below, along with the entire trial transcripts and key exhibit from this day (and we spent hundreds of dollars on the transcripts to make them publicly available for everyone, free of charge). You should read them and judge for yourself what they mean.

Then, in a separate post, we’ll bring you our update from lingering testimony from the FTC’s case-in-chief: Meta’s Alex Schultz, whose testimony spanned Weeks 4 and 5, Meta’s Steve Alison, and Bradley Horowitz, formerly of Google. Then, we’ll look at Meta’s first witnesses. And if you need some beach reading, consider our marathon entry covering three days of testimony from the FTC’s expert economist, Scott Hemphill.

What the FTC Did and Didn’t Show

This is where we left things on “groomer”-gate: on Day 14 (May 6) of FTC v. Meta Platforms, the FTC called Meta’s Chief Information Security Officer, Guy Rosen, to the stand. The point of the examination was to rebut Meta’s purported procompetitive justification for the Instagram deal that Meta’s investment helped Instagram grow and unlocked new security tools it could use.

The FTC wanted to show that years after the Instagram acquisition closed, there were still serious security problems with the app at the same time that then-Facebook was under-investing in its sibling app. The FTC did so by putting up a provocative slide deck titled, “Inappropriate Interactions with Children on Instagram” dated June 20, 2019.

It’s worth pausing here to note that, just before trial, Meta filed what’s called a motion in limine to prevent certain documents in this category from coming into evidence. The key parts of that motion, though, are redacted. From what we can read of it, Meta apparently demanded that the FTC withdraw a certain statement that the FTC included in the sealed versions of its summary judgment papers, which, according to Meta, the FTC agreed to do. Meta’s motion called that statement “irrelevant and defamatory.” It’s juicy, but we don’t know what statement it is!

Taking a look at the “lesser redacted” version of the FTC’s reply to Meta’s response to the FTC’s counterstatement of material facts (say that five times fast), paragraph 2258 is one that Meta’s motion in limine flagged as originally having been “defamatory", but it’s not clear if the version the public can see has removed that statement or not. This is what it says:

And so far as one can tell from the unredacted parts of Meta’s motion, the “Inappropriate Interactions with Children” deck (plaintiff’s exhibit 3612) was not something Meta sought to exclude. In fact, the exhibit was “pre-admitted,” meaning that Meta already agreed it could come into evidence by the time it was introduced. Chief Judge Boasberg denied Meta’s motion in limine before trial, but as we reported, prompted the lawyers from each side to move on from this topic during questioning, which he said was covered in an “awful” lot of detail.

When we saw the deck on May 6, we only saw the slides of it that FTC lawyer Susan Musser took us to. Meta’s counsel for the cross-examination of Rosen, Kellogg Hansen’s Leslie Pope, didn’t return to the exhibit. The defense’s points might have been too in the weeds to get into after the court encouraged counsel to move along. But there are some things from the deck that didn’t get aired that might have helped the defense—if not in the court of law, then in the court of public opinion.

The first thing to know about this deck is that it’s a “proactive risk investigation.” The FTC asked Rosen what that means, and this is how he put it:

Q: Now, a proactive risk investigation is an investigation focused on surfacing gaps and vulnerabilities across various surfaces and abuse types in order to identify systemic risk in Meta's policies, protocols, and enforcement. Do you agree with that?

A: It's a process that we have in order to surface where we can improve our systems, and it's really helped us drive progress in a number of areas throughout the years.

Q: So in other words, it identifies a problem and tries to find the root cause, is that right?

A: We have a process of mapping the root causes and ensuring we make recommendations of how we can improve our systems, which we have in many of these cases.

So this deck is Meta’s attempt to look for problems and then find root causes. Let’s start with the second slide the FTC showed after the title page:

We reported what it says here on the far left under “Problem”: “IG recommended a minor through top suggested to an account engaged in groomer-esque behavior.” Rosen seemed to admit this was a “problem” Meta found:

Q: And it says, IG recommended a minor through top suggested to an account engaged in groomer-esque behavior.

Do you see that?

A: I see that.

Q: And that is one of the problems that this PRI is investigating?

A: It appears to be one of the things they have discovered.

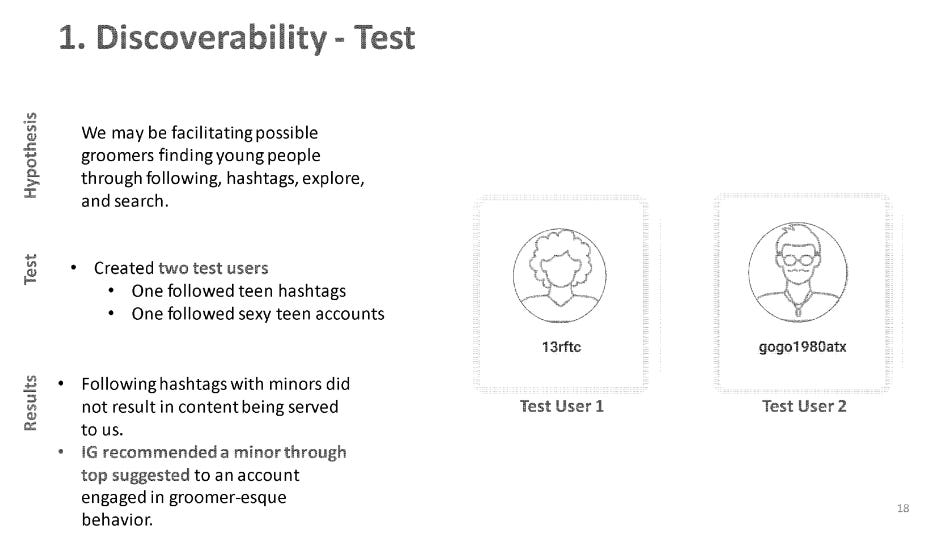

Sounds bad, right? But looking at earlier slides raises the possibility that this problem was identified only when Meta made “test” accounts that followed groomer-adjacent hashtags:

Again, we don’t know how Meta began with this test and ended with what’s called a “Result” on the last bullet of this slide. But the language of the last bullet on this slide is identical to the language on the next slide under “Problem”. That suggests—and this is just my opinion, making inferences from the evidence—that the “account engaged in groomer-esque behavior” was actually a dummy account created by Meta employees as part of a test.

The cover email to the deck says that the team used “a variety of adversarial testing methods” to surface risks, and then investigated their root cause. Turning back to the first of the two slides shown above, the “Root” analysis on the top right corner of the slide says: “The recommendation algorithm worked as intended.” So to infer from these bullets what may have happened: a dummy account created by Meta employees for test purposes to engage in groomer-type behavior had a minor recommended to it; this then triggered a deeper dive into the “root cause” of the problem, which is identified here potentially as simply that Instagram’s algorithm works as intended by recommending content based on current connections and past content consumption.

Now, even if it’s true that the recommendation discovery came from a deliberate test, rather than from an actual user, that gives cold comfort. It’s good that Meta was looking for problems like this, but that begs the question of why Instagram’s algorithm could serve up these recommendations to begin with. A defense that falls back on pointing out that test accounts are just that—as Meta has argued in response to investigations by The Wall Street Journal—is about as comforting as saying that no real children were crushed by airbags, only child-sized crash test dummies. Feel safe?

Interestingly, again looking at the second slide, which the FTC didn’t show, is that this team started with a hypothesis that “We may be facilitating possible groomers finding young people through following, hashtags, explore, and search.” But the team found that “following hashtags with minors did not result in content being served to us”—”us,” perhaps meaning the two dummy accounts. But even that’s hard to take at face value given more recent reporting. Here are some of the hashtags that were used in that dummy test:

In 2023—four years after the creation of this deck—The Wall Street Journal published an investigation into the hashtag problem, and its dummy accounts found even more troubling hashtags openly being used to sell child sexual abuse material, like “#pedowhore” and “#preteensex.” The Journal reported that (emphasis added):

Since receiving the Journal queries, the platform said it has blocked thousands of hashtags that sexualize children, some with millions of posts, and restricted its systems from recommending users search for terms known to be associated with sex abuse. It said it is also working on preventing its systems from recommending that potentially pedophilic adults connect with one another or interact with one another’s content.

Apparently, the “proactive risk management” was not aggressive enough.

While the 2019 presentation didn’t find a hashtag problem, it did find that the algorithm could recommend minors to accounts engaged in grooming behavior. That’s all context for getting to the payoff slide, which had some of the more disturbing statistics. As shown below, half of this slide is redacted for confidentiality. And that’s a big omission.

As we reported two weeks ago:

There’s a lot we don’t know about this statement: how did Meta track accounts that were “groomers” or “engaged in groomer-esque behavior”? And why were those accounts allowed at all? How did they generate that statistic?

We don’t know the answer to any of these questions from trial because no one asked them. And that alone is telling. Look at how carefully the FTC’s Susan Musser asked Rosen about this slide. Note how she intentionally asks only what the slide says, not what the slide means or if what the slide says is true (emphasis added):

Q: Yes. It says discoverability recommendations for groomers?

A: I see that.

Q: And it says overall IG, 7 percent of all follow recommendations to adults were minors. Do you see that?

A: I see that.

Q: It goes on to say, Groomers, 27 percent of all follow recommendations to groomers were minors. Do you see that?

A: I see that.

Q: And the conclusion was, in the bottom two bullet points, that Instagram is recommending nearly four times as many minors to groomers with nearly 2 million minors in the last three months. Do you see that?

A: I see that.

Q: And 22 percent of those recommendations resulted in a follow request. Do you see that?

A: I see that.

What do these questions establish? All they establish is that the words are on the page—which one could see from the exhibit itself, so they don’t establish anything! There’s a big difference, obviously, between data collected by Instagram in the ordinary course, and a potential experiment. But even a test can show a real-world problem with Instagram’s algorithm—in this case, a major flaw.

Meta’s “Response”

Here is what Meta has had to say about this exhibit, beginning with its statement as reported by Bloomberg (emphasis added):

“Out-of-context and years-old documents about acquisitions that were reviewed by the FTC more than a decade ago will not obscure the realities of the competition we face or overcome the FTC’s weak case,” a Meta spokesperson said in a statement.

The company added that it has “long invested in child safety efforts,” and in 2018 began work to restrict recommendations for potentially suspicious adults and encouraged the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children to expand its reporting process to include additional grooming situations it noticed.

The company in September launched Instagram Teen Accounts, which have protections to limit who can contact teens and are private by default. “They’re in the strictest messaging settings, meaning they can’t be messaged by anyone they’re not already connected to,” Meta said in a statement, noting that teens under 16 need a parent’s permission to change the settings.

The company also pointed to technology it introduced in 2021 that helps “identify adult[] accounts that had shown potentially suspicious activity, such as being blocked by a teen, and prevent them from finding, following and interacting with teens’ accounts.” The suspicious accounts don’t get recommendations to follow teens, “or vice versa.”

So the company says that they began work in 2018 to “restrict recommendations for potentially suspicious adults”. But the above exhibit is from June 2019! And that seemed like work was just beginning as the risk was only then being “proactive[ly]” assessed.

Here’s what Meta told Matt Taibbi:

“This six-year-old research shows just one piece of the work to improve our child safety efforts, which we’ve significantly expanded since then,” a Meta spokesperson told me. “We’ve spent years refining the signals we use to detect these accounts and prevent them from finding, following or interacting with teen accounts – or with each other – and we continue to focus on understanding these evolving behaviors. Our launch of Teen Accounts last year also places teens under 18 into the safest automatic protections, which limit who can contact them and the content they see.”

There’s a lot to unpack there. Let’s take the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (“NCMEC”) and then teen accounts in turn.

NCMEC Praises Meta As Meta Funds NCMEC

Meta repeatedly cited its work with NCMEC in response to the FTC’s allegations. Guy Rosen mentioned it in his testimony. Meta said the same at the summary judgment stage:

This is yet another explanation from Meta that at a surface level sounds passable. But in my opinion, it’s highly misleading. Look at how Meta quotes this statement on NCMEC’s website to make itself sound like a responsible, wonderful company. What Meta doesn’t mention is who actually wrote that statement on NCMEC’s website. I have no information one way or another, but I suspect that it’s the kind of flattering autobiography that corporations write for themselves. Look at the corporate sponsors page for NCMEC and decide for yourself who wrote this blurb:

Take a look at the whole page: it’s filled with Big Tech outfits like Amazon and Google.

It’s no wonder that NCMEC has kind words for Meta. Besides the government, Meta appears to be one of NCMEC’s largest cash funders in recent years. NCMEC’s annual reports don’t give specific donation amounts but disclose that Meta gave more than $1 million in 2023, 2022, 2021, and 2020, outpacing Amazon, Google, Microsoft, and TikTok; a 2024 report is not available on NCMEC’s website. Meta also made “in-kind gifts” to NCMEC totaling more than $1 million in 2021 and between $100,000 and $249,999 in 2022. A Meta employee isn’t on NCMEC’s Board of Directors anymore, but Meta’s Emily Vacher served on NCMEC’s board in 2022 and became corporate secretary in 2023; Antigone Davis of Meta held a board seat from 2020 through 2022.

Perhaps Meta’s outsized funding makes sense because most of the complaints NCMEC receives originates from content on Meta’s apps. The Journal reported that “Meta accounted for 85% of the child pornography reports filed to the center, including some 5 million from Instagram.”

But Meta’s generous gift-giving makes sense in another way: it smacks of reputation laundering, plain and simple. Meta gave millions to NCMEC, which in turn says nice things about Meta on the NCMEC website and handles the many reports of child pornography and other abusive interactions. When it comes time for a Congressional hearing or major antitrust litigation, Meta has statements from NCMEC praising it at the ready.

And NCMEC warrants a closer antitrust look given the epidemic of online harm of teens and children that has spawned massive multistate litigation by Attorneys General and multiple Congressional hearings. It could be—and I offer nothing but the material shared here, plus speculation—that NCMEC is a useful quasi-joint venture on this topic for the dominant Big Tech players (minus Apple). Meta has repeatedly claimed to compete against Microsoft (through LinkedIn) and Google (through YouTube), as well as TikTok. But by chucking their collective problems to NCMEC, these so-called competitors may be disincentivized to improve the safety of their products on their own.

Perhaps things are not as rosy anymore between Meta and NCMEC. In December 2023, NCMEC called Meta’s introduction of end-to-end encryption on Messenger and Facebook “with no ability to detect child sexual exploitation” a “devastating blow to child protection.”

As Mark Zuckerberg put it on Day 3 of trial, he could put “10,000” engineers on various problems, but at a certain point, there’s a cost tradeoff. This is a brutal calculus that sees 10,000 engineers as too costly, but recommending 2 million minors to “groomers” or 659,340 complaints from minors reporting adults for comments on Instagram (both over a three-month period per the trial exhibit) as costs Meta is willing to impose on others:

In a truly competitive market, would it be able to get away with that and invest without respect to reputational harm? Meta acts, as the French philosopher Jean Baudrillard put it, like “a jurisdiction which asks everyone to act responsibly while still granting itself the right to remain irresponsible.”

And it is usually only monopolies that can do that.

Further Reading

Meta likes to cite its Teen Accounts feature. But Accountable Tech partnered with Design It For Us to test the protections on Teen Accounts during a trial that finished May 4. Using five dummy accounts, they found that “5 out of 5 of our test Teen Accounts were algorithmically recommended sensitive content, despite Meta’s default sensitive content controls being enabled.”

Meta is simultaneously rolling out AI chat bots. Matt Stoller covered that in BIG here and here. Read this horrifying story of how another test account found that Meta’s AI chat bot based on John Cena’s likeness engaged in sexual talk with a test account purporting to be 14.

The Wall Street Journal’s reporting on this topic has been excellent. Here is an early 2024 report into subscription tools on Facebook and Instagram that “were being misused by adults seeking to profit from exploiting their own children.”

Transcripts & Exhibit

I offer no excuse… but how the hell did I miss this going on?? Am I the only person who’s just learning about algorithms hooking up minors with groomers??? 😧☹️

Advertisers cant boycott Facebook or Instagram over inappropriate content.

Meta controls both.

Neither has to "really-really" change as there is no competition in PSN apps.

John List, an economics professor at the University of Chicago and chief economist for Walmart.

Is there an antitrust case to be brought against Walmart ?