Google’s No Good Very Bad Start to Its Case

Google's cross of Dr. Lee was more compelling, and Judge Brinkema called Google's ad tech ecosystem a "spaghetti football."

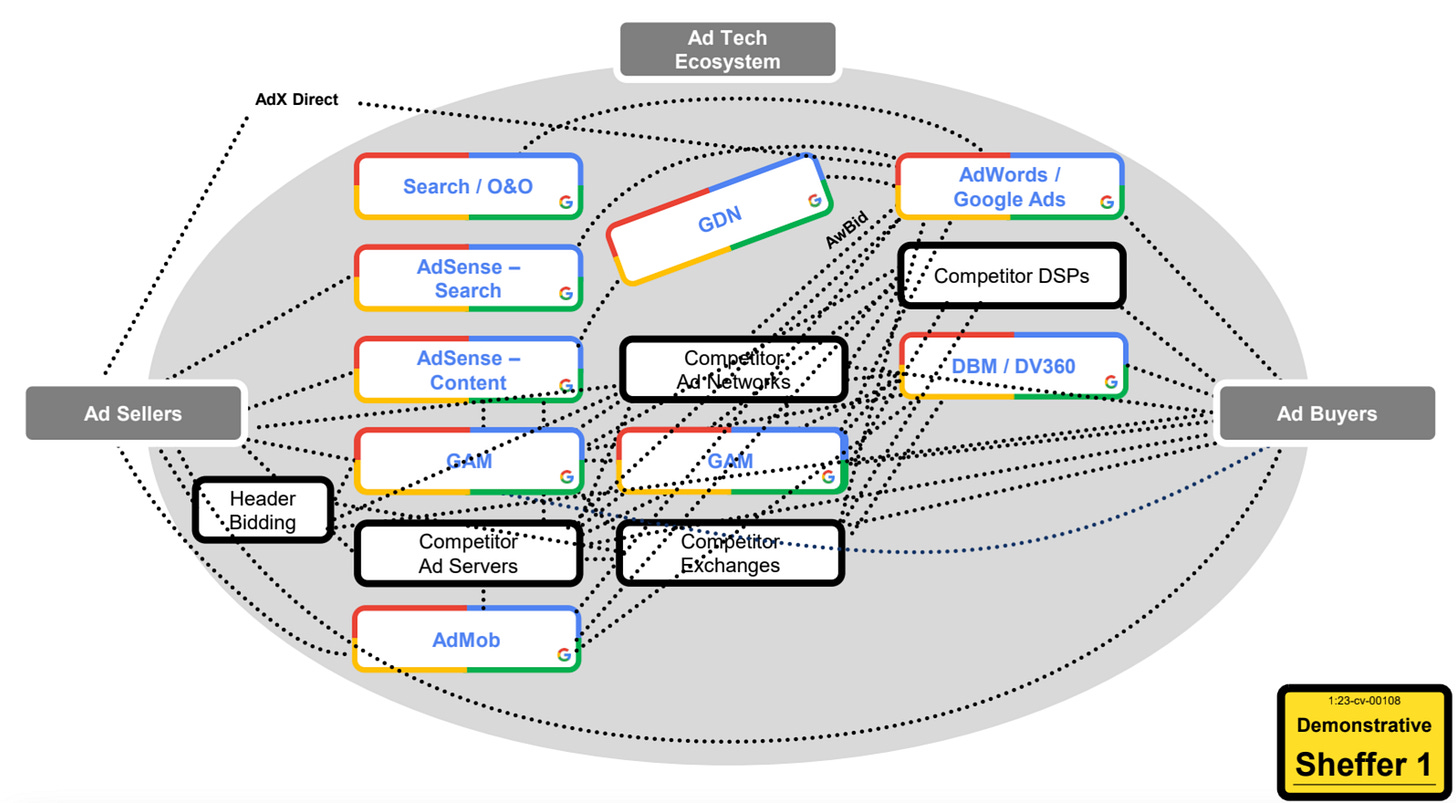

The “spaghetti football” in question. This is the exhibit Google used to open its case.

Day 10 of the trial began as expected, with Google lawyer Bill Isaacson’s cross examination of standout government expert Dr. Robin Lee. I won’t fully regurgitate Dr. Lee’s direct examination from Thursday (which you can read about here), as we have a ton to get to from today. But it was very strong, and very good for the government.

Naturally, Google needed to come in hard on cross. Little did we know the cross examination would be four-and-a-half hours long, the longest block of testimony from any witness thus far.

I’ll put the important takeaways up top, because this was a very long cross examination and there is a lot to recap. I thought Mr. Isaacson did quite well. Four and a half hours of standing on your feet and running a cross examination is tremendously exhausting. And Mr. Isaacson won the stamina battle. He landed some hits on Dr. Lee and there were some real areas of exposure for the government’s case, though it was saved by the bell when Judge Brinkema sustained several government objections (vagueness, “asked and answered,” etc.)

How much it will end up affecting the outcome of this case is a separate matter. But Isaacson got the assignment, and it was a tremendously difficult one. Dr. Lee, quite simply, is brilliant. He demonstrated mastery and computer-like recall on direct examination, making one well-articulated and evidence-based argument against Google after the next. I wrote on Thursday that this would be a battle of wits. After 4.5 hours on the stand, it also became of battle of will, and with enough time and pressure, lawyers like Isaacson will always find problems.

I think the length of the cross examination (twice as long as the direct examination!) came from the fact Google needed to draw out enough testimony from Lee to get enough material on the record, so that some of it would, inevitably, contradict, or be used to argue that it contradicts, bad-for-Google evidence elicited on direct examination. As the cross-examination wore on, Lee naturally became exhausted, asking Isaacson, nearly every few questions, to repeat his questions—a sign that a witness is tired and needs more time to think of answers.

Isaacson pressed Lee on the extent to which his quantitative analysis was based on the data of Dr. Mark Israel, a Google witness we will hear from. Lee contested this, and was taking more time before answering, unlike on direct where he quickly fired off answers. It makes sense—he’s a government witness and had a friendly examiner going through prepared testimony.

At counsel tables, Karen Dunn, who has thus far blended in, wearing neutral colors and getting less screen time than other Google lawyers who have been doing much of the legwork on cross and re-cross, came in today wearing bright orange—ready to take the lead on the first day of Google’s case.

As has become routine, Google highlighted data that could be construed as favorable to its arguments—focusing on Figure 7 in Lee’s report that showed Google’s win rate percentage in bidding going down for AdX over time.

Much emphasis was focused on the Google “nightmare scenario” where Facebook and Amazon take control of ad selection and “develop it into a DFP replacement.”

Isaacson asked Lee if this was already happening with The Trade Desk. He then asked Lee if he would “agree that competition from header bidding incentivized Google to innovate.” Lee said that it did.

At this point I jotted in my notes that “Google is getting its money’s worth.” While everyone generally agrees Google has a hard case, the lawyering for the most part has been top notch, with Google clawing at every bad fact, argument, and issue it can get its hands on. As I’ll get into below, this trend came to a grinding halt when Google finally started its case-in-chief.

I also noted that on this cross examination, Isaacson was taking some big swings that have been missing from the more technical hole-poking arguments of other cross examination.

Lee agreed that header bidding was a competitive threat to Google. When Isaacson asked Lee if header bidding had constrained Google’s market power, he noted, perceptively, that Lee had dropped “supra competitive fee” (meaning pricing above what can be sustained in a competitive market) from his answer, exploiting the appearance of contradictions or backpedaling.

Isaacson is good.

Next Google showed the Criteo SEC 10K report, and the government objected on hearsay grounds, which was overruled. While the government has been largely successful at blocking the admission of what has become Google’s go-to exhibits for impeachment—alleged rivals’ annual reports that often contain recitals to investors about the “competitive environment” the company is in (to play up the notion of Google having competition)—objecting on hearsay grounds in this instance was insufficient. These reports are made under penalty of law to a government body, are public records, and are not being offered for their truth.

Amazingly, on Google’s surreal start to its case-in-chief (which I will get to below) Karen Dunn would try, once again, to Trojan Horse into evidence The Trade Desk’s statements to investors of a similar sort to those that were tossed out by Judge Brinkema last week after a heated objection battle on the topic. Google’s lawyers love this type of evidence, because it contains broad statements related to competition by rivals that can be worked in to support Google’s case.

I actually spoke to an expert on corporate law, mergers & acquisitions, and these types of issues from Stanford earlier this week who was also a professor of mine at BC Law, to run through some questions I’ve noted during this trial. I asked about these types of corporate documents, which have caused some of the most pitched battles over evidence in this case, specifically the extent to which the statements Google is targeting, where rivals describe the market as competitive, are actually significant, or just corporate lawyer boilerplate.

He told me that “competitive” can mean many things, and it is unlikely that all of these reports Google wants to point to are actually Google rivals talking about how fiercely competitive their industry is among market participants. They could be referring to competition over talent, margins, technology, clients, etc. In other words, one company’s notion of “competitive” differs from another, and it is unlikely they are all speaking to a rich tapestry of rival firms competing in a healthy ecosystem.

Dr. Lee began feeling the heat, unable to recall a number of details from his report when Isaacson would press him on them. Sensing the blood in the water, Isaacson began digging in.

“You are not opining that there is a relevant market for display ads?”, Isaacson asked. Isaacson also asked if the relevant market in this case could actually be all transactions for ads.

Google can dream.

Google then went back to pointing to growth across the board in US display, native, and video ad spending. The counterpoint to this of course is Dr. Simcoe’s previous testimony in this trial (and great quote I noted on Thursday) that when “Standard Oil had a monopoly, the oil industry was still growing.”

An objection battle then ensued over whether Isaacson could ask Lee about eMarketer’s definition of display ads. Judge Brinkema ultimately ruled Isaacson can ask Lee about it, but that the eMarketer definition would not be admitted as evidence.

Isaacson needled Lee about his omission of Google AdSense from his reports. (Google launched AdSense in 2003 to give advertisers access to inventory from non-Google publishers.) Lee contended this is because AdSense is not an ad exchange. Lee further opined that there are different relevant markets based on the size of a publisher or advertiser. In other words, market participants of different sizes may prefer different ad channels.

Google then put up data that showed between 2019 and 2022, Google’s market share among ad exchanges for all US display ads was flat. This data came from Dr. Israel’s report.

However, Dr. Israel apparently included connected TV and other platforms in this data—Google attempting again to zoom out from open web display ads and reframe the market more broadly.

It would have been interesting (and stronger) for Google to develop arguments rebutting an illegal monopoly in open web display ads, taking the government head on, instead of trying to redefine the market exclusively. Google’s unwillingness (or inability) to do so feels like a concession of the point.

Isaacson then embarked on a humorous and drawn-out hypothetical based on a hypo from Lee on direct examination the day before. On direct, Lee had attested that in order to determine if a gas station chain had a monopoly, you would look to the sales of gas in that area, not the sale of potato chips sold inside the gas stations in question. This is an analogue for Google looking at ad markets other than the alleged monopolized market of “open web display ads.”

Citing this example, Isaacson asked Lee about the circumstances under which consumers would pay more for Coca Cola than Pepsi, or more for a Big Mac than a Whopper—or more for a Chiquita banana than a Dole banana. All of this caused Judge Brinkema to ask Isaacson if he’s hungry. The entire courtroom laughed. Isaacson was getting at alternative reasons why consumers would pay above competitive prices for Google, i.e. the idea that market participants may develop non-price based preferences that explain their behavior.

Isaacson asked Lee to confirm that as of the end of 2022, there were more than 100 ad exchanges, and if Lee evaluated all formats of ads in his report.

This is an illustration of the trope in law and policy circles that you can make data say whatever you want. Who are these 100 alleged ad exchanges? What of the fact Google is orders of magnitude larger than its next closest rival (which Dr. Lee called attention to), never mind ad exchange #100? We’ll never find out, it’s not the point.

Things got a bit dicey for the government when Lee admitted he had not in fact seen “open web display ads” defined before this litigation, or seen these words together. He also admitted he was not defining an open web display ads market, and could not recall “seeing” one.

Of course, how much these things matter at this point given the volume of evidence in this case is debatable. And we’ve heard plenty of testimony from actual digital ad market participants, from publishers to advertising agency execs, acknowledge industry recognition of “open web display ads” long pre-dating the trial.

Dr. Lee was getting tired here, and I can’t blame him. In the gallery people were having trouble sitting upright and paying attention. Folks took turns going for walks and to stretch. Pens were down. There was groaning and whispers of disbelief as this cross examination crossed the four-hour mark.

Isaacson then had a cunning line of questions for Dr. Lee: To avoid alleged anticompetitive conduct, would Google necessarily be forced to deal with its rivals? If so, would Google need to make all of its demand available to rivals in order to not be considered anticompetitive, or only some of it?

This is a really good question. Lee either has to say Google must make all of its inventory available to its rivals, a plainly unreasonable and unjustifiable expectation at odds with the law, or in the alternative, quantify how much (some) of its scale it is expected to offer to rivals, and then likely be asked why that amount is correct, and how he arrived at it, things Isaacson knew Lee would not be able to answer, particularly given the fact it is unclear how one would answer that. In terms of percent? Dollars? What type of ads, and through what channels? At what rates? What studies have you done, Dr. Lee, to establish this? You mean you are alleging my client must offer, for free, its scale to its competitors? What are you basing this on?

You can see how that’s just a white-knuckle line of questioning for the government that exposes gaps. It also reframes this case not as one about “tying,” but as a “refusal to deal.” The facts giving rise to Tying and Refusal to Deal claims can be very similar, and the distinctions can seem muddled, but the law on RtD is much friendlier to Google.

Lee struggled to formulate an answer, and essentially demurred. Seeing her witness struggling, Julia Wood jumped up to object for the government, arguing this question is calling for a legal conclusion. Judge Brinkema sustained the objection, on the grounds it was getting towards remedies in the event Google were to lose.

Dr. Lee, and the government, were saved by the bell. Of course, I say this with the usual caveat that given the strength of the government’s case thus far, it’s hard to know how much a response would have mattered. But if Judge Brinkema allowed this line of questioning to continue, or if Isaacson framed it a bit differently to avoid asking an economist for legal conclusions, it’s not apparent what argument the government has to plug this gap. (Note to self: Keep a close eye on this issue. It will surface again in Google’s case.)

Isaacson then asked Lee if he knew DoubleClick had a 20% take rate before Google acquired it—with the question obviously being offered to get into evidence a non-anticompetitive rationale for the beleaguered take rate issue—that Google was able to sustain a high and unchanging take rate regardless of Google’s features, competition, or market conditions.

Isaacson then pounded Figure 110 from Dr. Lee’s report that showed some competitors had higher take rates than Google. Lee countered that these are very small rivals.

At long last, the cross examination ended. Redirect was brief, focusing in part on a 2018 Chris LaSala email expressing worry that if Google bought through all third party ad exchanges, its 20% take rate would “crater.”

Judge Brinkema then praised Mr. Isaacson’s less than five minute re-cross, and asked Ms. Wood if she was ready to “say the magic words.”

She was.

“The plaintiffs rest.”

And just like that, Karen Dunn hustled to the podium, kicking off Google’s highly anticipated case-in-chief, calling as its first witness, Google executive Scott Sheffer, VP of Publisher Partnerships.

Then things went off the rails.

Google decided to start its case by having Mr. Sheffer “create” a demonstrative of the “ad tech ecosystem.” This of course would be Google’s retort to the great many charts the government has used depicting its view of the Google-dominated power structures in the industry.

Let’s “fly the plane while we are building it,” Ms. Dunn said.

Only this plane, as we would soon see, appeared to be manufactured by Boeing.

This was a basic Powerpoint style chart, and was clearly pre-planned with Mr. Sheffer. The boxes and the names of the parts of Google and ad tech plumbing were already entered. With Mr. Sheffer making reference to, for instance, Google AdWords, the legal team’s technologist was able to move to a new slide, making this box immediately appear on the screen in position.

The only thing not pre-made were the lines depicting the connections between each part of the “adtech” ecosystem. Mr. Sheffer would call out where the lines showing these connections were to go, and Google’s legal team would draw the line on the computer, making it appear on the screen.

Very quickly, this turned into a disaster. Doing anything like this, on the fly, in court, during the opening of your case-in-chief, is risky. Having the certainty that it will go off without a hitch, and also look professional, is extraordinarily risky.

While other watchers of the case have blasted this exercise, I do see the merit in it. It makes sense for Google to get its competing version of events in the record, as to not only what the ad tech ecosystem is in its view, but how it came to be that way.

Mr. Sheffer focused on Google’s history, tracing some of these Google properties back to 2003. This is an interesting pivot from the government’s story, which in large part began after 2008 with Google consuming DoubleClick. It’s showing organic success, not merely an anticompetitive incumbent that has always been that way.

But things unraveled. With each new connective line being drawn on the fly, the chart very quickly turned into a mess. Lines were covering the text of what some of the boxes on the chart were. Some of it was not straight, one of the boxes was crooked, it was hard to both read and follow. But most stunning was the fact lawyers of this caliber would unfurl something so shoddy.

What has gone unmentioned by many (and if I were the fact finder in this case, what I would drill down on more than just a sloppy exhibit) is that it arguably made Google’s dominance appear even worse, by virtue of the fact there was basically just one box in this giant Google diagram representing competing ad networks, and another representing competing ad exchanges. On top of that, the competing exchanges appeared to have fewer lines connected to them, underscoring the extent to which rivals are excluded and minimized in the ad tech ecosystem.

In the overflow room, government lawyers were actually laughing at this, and members of the media and other interested parties were not far behind. This thing was really a mess. It had the feel of those old John Madden NFL broadcasts where Coach Madden would take the telestrator pen to try and diagram double coverage put on to stymie Marvin Harrison, but instead it just looked like unintelligible scribbling.

After sleeping on it, I agree with what I wrote above concerning the benefits of this approach. I just think the “debacle” aspect came with respect to the line drawing simply not going as planned from a technical standpoint. First impressions mean a lot, and this was very bad.

With Karen Dunn having told the court at the end of the day on Thursday that Google intended to finish its case by this coming Wednesday or Thursday, given what we saw on Friday, there is simply no way Google will be able to affirmatively challenge the balance of the government’s case in this time.

I don’t think Google is going to successfully contest its market power in the government’s proferred trifecta of markets. Instead, Google’s strategy is to pound an alternative market definition, try to win on a narrow interpretation and application of the law (steering the case toward a “refusal to deal” analysis), and put faith in the Fourth Circuit, SCOTUS, and potentially changing political tides affecting the government’s continued resolve on this case.

I think it would have been far stronger, and far more interesting, for Google to instead come in guns blazing, and attack the government’s claims head on—offering alternative pro-competitive reasons why the market does not have stronger competition, providing alternative evidence that shows Google offers consumers more than anyone else could by virtue of its scale and integration (which Google would argue was earned on the merits!), and explaining how it is in fact feasible for a publisher to build their own ad server (Kevel even provides this service!), but they choose not to because Google provides a superior service (not only because they control ad demand!)

If Google loses, the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals will not hear publishers and ad agencies be hauled in again to blast Google in vivid detail. Appeals courts in the United States are concerned with legal questions, and far more deferential to lower courts on factual determinations. With the most overwhelming evidence made two dimensional and buried in the record, and with the finder of fact (in this case, Judge Brinkema) already having dealt with that end of the case, Google could then play to its strengths and not its weaknesses, alleging that antitrust law has been misapplied, etc.

The government, wanting to lock this museum piece exhibit into the record, asked Judge Brinkema for the same, and she instructed Google to print out this diagram to be saved into evidence.

Moving on, Scott Sheffer testified that publishers are finding success with Amazon, using IMDb (which apparently uses both Amazon and Google) as an illustrative example.

Mr. Sheffer also mentioned PBS, the Harvard Business Review, Nordstrom, Walgreens, and others who use GAM, but not AdX, playing up publisher/consumer choice and the potential of Google rivals. He also discussed how Microsoft’s acquisition of Activision-Blizzard (ironic because that deal attracted significant antitrust scrutiny in its own right) has allowed Microsoft to make inroads in the youth interactive market. The takeaway from this testimony is that Google is living and dying by a broad market definition. When Ms. Dunn asked Mr. Sheffer if he had heard of “open web display ads,” he said no. He said, she said.

Attention then turned to The Trade Desk’s earnings calls, and how Google reacted to The Trade Desk’s outlook on competition. This turned into another fierce objection battle over the admissibility of this evidence.

Ultimately Judge Brinkema called the testimony highly questionable, and that it is tainted given Google’s notice of lawsuits against it at the time. Not a great start for Google.

To close out the day, Benneaser (Ben) John, VP of Engineering at Microsoft AI, testified briefly via deposition read-in, which was largely aimed (again) at diluting market definition.

This was a long day, and it’s hard to believe this trial is headed for the finish line next week. It will be interesting to see where Google goes next, and how this one ends.

Stay tuned!

From reading this I am really feeling like I’m in the courtroom. I was getting weary through the 4.5 hour cross of Dr. Lee and befuddled by the drawing with lines going all over the place. Good stuff!

You managed to make this hilarious as well as informative and engrossing.