Day Two: Can the Open Web Be Restored? And an Annoyed Judge Tries to Move Things Along.

The Google remedy trial finishes up with business, looks forward to the technical possibilities of a remedy. One witness discussed journalism: “They’re starving. They just need food.”

Day two of the Google adtech remedy trial picked up a little speed, but not enough for Judge Brinkema. By late in the day, her patience was wearing thin, which has important implications for the possible outcome. We’ll get to that.

But first, hit the subscribe button to get regular updates on the most important monopolization trials of our time:

There were four industry witnesses testifying today, all called by the Justice Department, and the themes were similar to those from Day One.

Is a break-up necessary to cure Google’s monopolistic behavior? Each industry witness says yes, but on cross-examination by Google, they are all asked why it’s not enough for Google to just cease bad behavior instead of forcing a break-up. They assert that the complexity of high-speed digital auctions with many buyers, sellers, and exchanges placing diverse ads on diverse websites just presents too many cheating opportunities for behavioral rules to fully prevent.

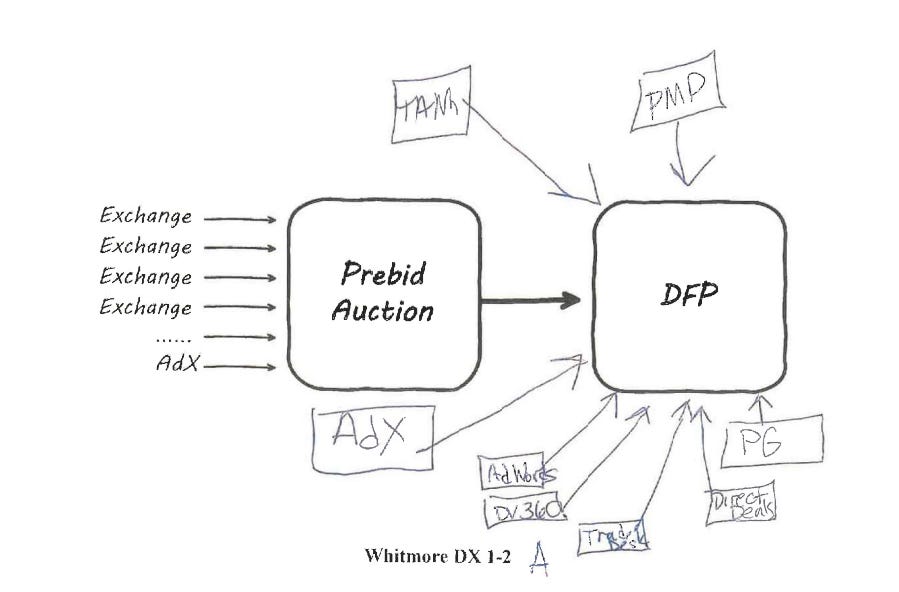

(Here’s a complicated graphic presented at trial yesterday on places where Google could influence the market should the judge only place behavioral remedies on the adtech giant.)Is breaking up Google viable? All say spinning off AdX and DFP would be easy, and on cross are presented with ways Google’s size makes it different from any experience they have had with merging, buying, or switching other companies.

Lawyers from one side or both always ask each witness if malware, fraud, and privacy will become problems when they have left the sheltering protection of Google’s strong arms. (It is Google’s theme, but DOJ often asks it preemptively.) The witness always explains that every company of interest here is fully competent to handle these security issues. One of yesterday’s witnesses, Grant Whitmore, had the best expression for this: he called security concerns “table stakes”; the ability to handle security is a minimum ante any company has to put up for a seat at the table.

Google lawyers put each witness through a series of questions about training and experience to explicitly establish—on the record—that the witness is not an engineer qualified to give an expert opinion on the feasibility of divestiture. This pattern will probably change tomorrow, when we will start to hear from the engineers. More on that, too, later.Is Google chastened since found liable for monopolization? The DOJ lawyers ask each witness if they have noticed any change in Google’s behavior in the year since the trial or even in the five months since Judge Brinkema found Google liable. None of them ever have detected even the smallest change in Google’s overbearing behavior. (I’m always inclined to believe the witnesses, just because I’m a trusting soul, but I totally believe them on this one.) The Google lawyers ask each witness if open-web display ads are on the way to extinction, as the internet moves to walled gardens and video advertising. Everyone acknowledges they are diminishing, but all the witnesses defend the plucky open-web display ad and their faith in its vibrant future.

Let’s get to the witnesses. Today’s first witness, Kevel CEO James Avery, started us off on an interesting and unfamiliar topic.

Witness: James Avery, CEO of Publisher Ad Server Kevel

James Avery is the CEO of Kevel, an ad server company with about 50 engineers. Avery’s theme was migration. DOJ sought to get the judge to see that migrating AdX and DFP out of Google is a manageable task that people do all the time, not the apocalyptic nightmare Google would have us believe.

Kevel recounted a number of different projects migrating services from one platform or host to another. He emphasized Kevel’s success at managing change without any downtime for their 150 customers. His company handles 20K to 100K ad requests per second, and works on Amazon Web Services (AWS), a cloud server. Kevel updates systems weekly, on a rolling basis to avoid downtime. They are in the midst of adapting their system to work on Google Cloud Platform (GCP) as well as AWS. It is a year-long, 20-engineer project and, again, will entail no customer downtime.

After the migration tales, DOJ attorney Michael Woolin walked Avery through familiar questions about the two sides’ remedy proposals. Avery is firmly in favor of full divestiture of DFP, rather than divesting just DFP’s Final Auction Logic first and the remainder later and only if necessary. He said that moving the Final Auction Logic out of Google and making it open-source was straightforward, and a number of companies were capable of hosting it, including IAB Tech, the W3C, and Prebid. He expressed an interest in buying AdX and DFP, if they were divested, which would require financing, probably from private equity.

On cross-examination, Google’s Erin Morgan got Avery to admit he trusted Google. It is not an unusual confession for witnesses to make, as one of the themes of this trial is that Google is extremely competent, due to its monopoly giving it more and better data to inform its ad tech tools and enable it to test and refine its processes. But none of the witnesses trust Google to treat its customers fairly, let alone its competitors, which is also one of the trial themes. She also got Avery to admit he had never migrated a system into the cloud, and noted that Kevel’s 20 thousand to 100 thousand ad requests per second were a bit short of Google’s 8 million per second.

Witness: Luke Lambert, Head of Reputation Marketing & Insights at Omnicom Confluence

Luke Lambert, of the Omnicom Media Group, was today’s second witness. He, too, praised Google, calling AdX a “good product” that was “seamless” in its interactions with DFP. At the same time, he was not surprised by the finding that the company was guilty of illegal monopolization; he said no one was surprised, bringing a swift objection from the Google lawyers as “hearsay,” which Judge Brinkema sustained. Lambert thought the root of the liability finding was Google’s lack of transparency, and his testimony focused on that. And money.

Lambert’s company’s clients are advertisers. They want to know where their advertising dollars go. Whatever does not go to the websites where their ads land goes to fees, and Google takes fees far above industry norms. He has to be able to justify to clients what was done with their money and what happened in the auctions where they bid. But Google’s lack of transparency makes that hard. That’s why behavioral remedies are inadequate. Not only is the Final Auction Logic a black box, but the whole system is too complex to identify all the opportunities for manipulating this or that part of it. As long as Google has the power to rig things in its favor, it will find ways to keep its take rate up and his clients’ margins down. Divestiture is necessary.

Witness: Jay Friedman, Strategic Advisor and former CEO at Goodway Group

Jay Friedman, Marketing and Advertising CEO at Goodway Group, Zoomed in to hit all the points I mentioned earlier as DOJ’s common questions. But he went two steps further than we’ve heard before. He is concerned with the huge size of DFP even after divestiture. It should not be in the hands of one buyer, which would then have most of the corrupting incentives that Google succumbed to. He suggests breaking the divested company into two parts or more. Alternatively, perhaps the entirety of DFP, not just its Final Auction Logic, could be open-source.

The other new idea he offered is that AdX should not just be divested but eliminated. Once it is outside of Google, it is just another ad exchange. Friedman thinks we have plenty of ad exchanges. And depending on the buyer, it could still be a source of trouble. To the extent Google is arguing that AdX cannot be sustained as a viable standalone business, it seems those participating in the industry either disagree or don’t care. An exchange is an exchange is an exchange - unless it is a tool of Google’s monopoly.

Friedman also had misgivings about behavioral remedies, whether from DOJ or Google, that left Google with the huge advantage in data it currently enjoys. He thought rules about what it could or could not do with the data (e.g. prohibit using first-party data to privilege itself) were inevitably too little. As long as Google has a monopoly’s advantage in data, it will find a way to exploit that data for its own benefit.

Lambert returned briefly to the stand to complete his cross-examination after the Friedman Zoom call ended. The most notable thing about this short stint was Judge Brinkema’s response to some objection: “Objection: Goes well beyond the open web!” Brinkema: “That’s been one of the themes here for quite a while.”

Witness: Jed Dederick CRO of The Trade Desk

Jed Dederick, Chief Revenue Officer of The Trade Desk, a demand-side platform, was the final witness of the day. His first answer was how he felt when he heard the Google liability decision: hopeful. The market for open-web display ads has been “anemic” for years, and enjoyed little innovation compared to other advertising technologies. He was hopeful that this Google verdict might be a turning point.

He says we (meaning “we” on the ad tech demand side) have lost trust in the infrastructure. We wonder where our money goes. Lack of transparency is the cause of this loss of trust. Advertisers want our ads to perform. But Google’s dominance on the sell side gives AdX a sky-high take rate and drives our revenues down. If trust were restored through transparency, money would flow back into open-web display advertising.

It was a movingly optimistic view—the open web can be restored—after so much testimony on the sector’s decline. Later, on redirect, we got a reminder of why this is trial is so important, why the remedy imposed here could matter so much. A page was displayed from a Trade Desk publication showing the Best of the Open Internet; they were, quite simply, American journalism, most of our heritage media. That’s what open-web display ads fund. Dederick saw it as a list of great opportunities for advertisers. He does not think the sector will disappear, that it is just showing the effects of a corrupted adtech market on these sellers: “They’re starving. They just need food.”

Judge Brinkema Gets Annoyed

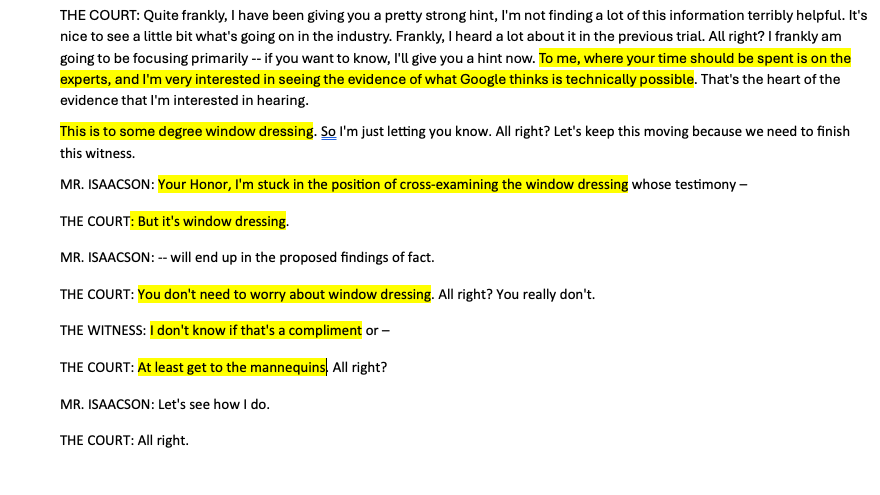

During Dederick’s cross-examination by Bill Isaacson came the day’s most significant event. Provoked by some particularly weedy line of questioning—I think it was Isaacson asking Dederick if the Final Auction Logic includes anything other than the auction logic of the bidding—Judge Brinkema said she wasn’t interested in these lines of questioning, that what she wanted was to get to the engineers, that she was particularly interested in what the Google engineers thought was technically possible.

Here’s Jason Kint with the transcript of that moment.

When both lawyers started to explain the line of questioning, she interrupted, “It’s window dressing. You don’t need to worry about window dressing. At least get to the mannequins!” When they started again on some weedy disputes, she turned to Dederick and asked, “Do you know what they’re talking about?” to which he could only say, “No.”

At the end of Dederick’s testimony, DOJ lead attorney Wood told Judge Brinkema that they would like to change the schedule and will try to line up the engineer witnesses for tomorrow morning instead of Thursday. And they will then rest their case, and Google will present their view. Rocket docket indeed.

As U.S. vs Google notes, “the parties have proposed November 3rd for submission of post-trial briefs, and November 17th for closing statements.”

This trial is going fast!

Long ago ... long, long ago, I covered a hearing into an application from McDonalds to open a restaurant with a drive-through in a certain community. Locals opposed the drive-through. McDonalds said they couldn't run the restaurant without one. They didn't get the drive-through, they opened the restaurant, and decades later, it's still operating. For some reason, today's coverage brought that incident back to me.