Day One of the Google Monopoly Trial: "Those that fail to learn from history are doomed to repeat it.”

It's the opening, as the government and Google duel on the law and the facts. There are two witness. DOJ and Google engage on divestiture, and Google’s behavioral remedy proposals start to dissolve.

For other comprehensive discussions of the day, see DCN’s Jason Kint and the site U.S. v Google from Check My Ads.

Day one of the Google adtech remedy trial started on a suitably lofty note, though both sides were well into the technical weeds by day’s end. Julia Tarver Wood, the Department of Justice’s lead attorney for the trial, opened with Winston Churchill’s famous warning: "Those that fail to learn from history are doomed to repeat it.”

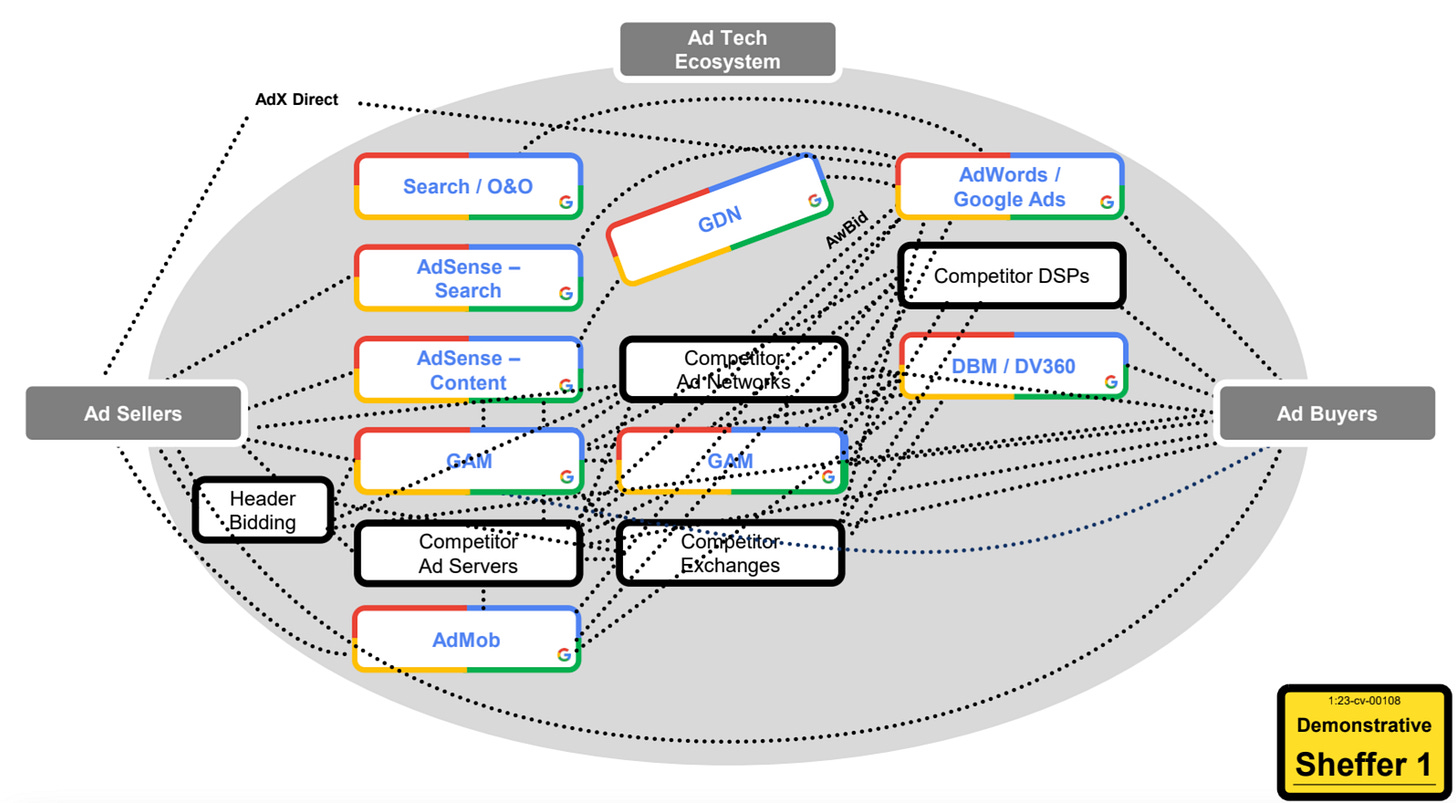

Before going on, I want to offer two caveats. First, as a philosopher covering this trial, I feel bound to point out that Churchill’s deservedly admired words of wisdom were written by the philosopher George Santayana forty years earlier. Second, adtech is complicated and weedy. Here’s an exhibit Google used in its opening last September of the first phase of the trial, you can see how weird these markets are. So if you don’t follow everything, don’t worry!

The Opening Statements

Ok, on to the openings. First, Wood urged the court to learn from Google’s history of bad behavior—now three monopolization convictions long—and not allow the recidivist monopolist (as she called Google) to keep both the power and the incentive to repeat its crimes. The way to prevent a repeat, she argued, is structural remedies: divestiture of its ad exchange, AdX, and of the Final Auction Logic part of its publisher ad server, DFP.

Wood contrasted DOJ’s strong structural proposals with what she called Google’s “toothless behavioral remedies” (paraphrasing Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson). The remedies Google proposes, Wood argued, would fail to achieve any of the four goals of antitrust remedy she finds articulated in Supreme Court precedent (most recently, US v Microsoft):

1) “unfetter a market from anticompetitive conduct”

2) “terminate the illegal monopoly”

3) “deny to the defendant the fruits of its statutory violation”

4) “ensure that there remain no practices likely to result in monopolization in the future.”

Google’s merely behavioral remedies would, she claimed, leave the ad exchange market broken, retain Google’s dominant monopolies, allow it to keep the ‘illegal fruits’ of massive data and scale advantages, and leave in place the ability to monopolize once again, buried in code and hard to detect. Only a structural remedy could accomplish the four required goals. It was an impressive opening.

Karen Dunn, Google’s lead attorney, then made her opening remarks. They were capable, but less impressive. Following Wood’s articulation of those four goals, it was striking that Dunn neither disputed the correctness of those goals nor argued that Google’s remedy proposal would meet them. Rather, the behavioral remedies she described focused on eliminating the illegal activities and restoring competition to the markets.

In particular, Google proposes to undo the tying between AdX and DFP by putting PreBid between them (which I’ll come back to), and accept rules against (and monitoring of) those various shenanigans they perpetrated to rig auctions (First Look, Last Look, etc.). Her other main argument was that legal precedent did not endorse divestiture as a remedy in cases like this, that it was both unprecedented and unworkable. She, too, quoted Microsoft, advising that remedies “should not embody harsh measures when less severe ones will do.” This raised the question that recurred repeatedly in everyone’s testimony for the rest of day: will less severe measures do what needs to be done to curb Google?

Dunn claimed that technical difficulties were far greater than DOJ understood, and that these structural changes would intrude far into the future of an industry already rapidly changing. Lastly, she made a consumer welfare argument that Google’s behavioral remedies go as far as it is possible to go without breaking the technology that millions of people rely on. And so ended opening remarks.

The First Witness: A Frightened Publisher, Grant Whitmore

DOJ’s witnesses were from competitors to Google in the two markets Google illegally monopolized. The first, Grant Whitmore, was VP of Ad Technology and Programmatic Revenue at Advance Local, a publisher. Fluent in industry discourse, Whitmore occasionally asked for questions to be restated, and it became clear that he was *incredibly* nervous. At one point, someone asked him (It may have been Judge Brinkema, but maybe Wood), “Have you testified much in court?” to which he replied, “I certainly have not!” at which everybody laughed. His nerves, which came either from being a witness in court, or speaking openly against Google, served to validate him as a trustworthy source.

Whitmore covered a lot of technical territory in several hours of testimony. His thesis throughout was that divestiture of both AdX and DFP was necessary to significantly change Google’s destructive role and repair the publisher ad server market in which his company competes. (It’s notable that the DOJ isn’t asking for an immediate divestiture of DFP, meaning Whitmore wants a more aggressive remedy than the government.)

Whitmore’s rationale was straightforward. Google’s high take rate cuts his margins. Google is just hard to deal with and says, “We won’t accept any red lines for this contract,” meaning they set the terms, take it or leave it, in a business where publishers have many diverse concerns about what gets posted on their websites. But DFP is too large not to deal with, because if you don’t use Google’s software, you don’t get access to the ad demand from AdX. Moreover, the Final Auction Logic within DFP, which is how the final decision on bids gets made, is a “black box,” so no one knows how winning bids are picked; they can neither adapt their own strategies to it nor trust that Google isn’t self-dealing.

Whitmore argues that divesting just AdX is not enough, because Google adapts and DFP’s control would remain even without an in-house exchange. So, DFP would need to also be divested. He believes companies sell parts off all the time, that there are many competent companies who could step up to run divested AdX and DFP. Switching costs would not be high, and most clients would hardly notice a change in ownership. Similarly, capable hosts would come forward to manage the open-source Final Auction Logic.

Whitmore did not think Google’s remedy proposal would work. He mentioned that the most valuable and fastest-growing parts of his business are outside standard auctions and excluded from the protections Google’s behavioral remedies offer. It came out that most of those remedies include a caveat that they apply only to “Qualifying Open Web Display Inventory” (the phrase occurs 22 times in Google’s proposed order). It turns out there are a lot of different kinds of inventory, auctions, contracts, and deals. The jargon startd to close in, and even the professionals struggled with discussing programmatic guarantees, private auctions, preferred deals, and more. Apparently, Google’s proposed behavioral remedies, as written, only applied to a narrow range of behaviors. Just as this was starting to look like a loophole a company the size of Google could squeeze through, Judge Brinkema broke in with a sensible suggestion: if we delete the caveat and extend the measures to all bids, would that do? That was unclear, but it seemed possible some modified version of these behavioral remedies might work.

And that brought us back to PreBid. Recall that Google proposed to break the AdX tie to DFP by interposing PreBid between them. PreBid is the software Google’s competitors came up with to enable “header bidding.” This is a way around AdX rigging auctions. Websites embed code in the header so while the website loads, all the non-AdX exchanges hold an “auction of auctions” (as today’s second witness, Andrew Casale called it), and choose the winning bid in the split second before AdX holds its auction. They then submit this known winning bid to AdX, so it can’t undercut them but must either accept that bid or beat it. Google’s proposal to prove it will stop tying (put PreBid between AdX and DFP), is essentially to have AdX join the header bidding and submit bids to PreBid which submits its winner to DFP. The auction is then, seemingly, outside Google’s control.

As people (particularly Julia Tarver Wood) start looking more closely at the fine print of Google’s behavioral remedies, though, it appears that AdX has to submit to PreBid, but it is not forbidden from also submitting directly to DFP. And this leads to the graphic of the day (which I wish I could show you, but it won’t be available until sometime tomorrow, I think). In his long, ineffective cross-examination of Whitmore, Google attorney Bill Isaacson displayed graphics of the current situation versus the situation after their behavioral remedy. The after-graphic showed AdX obediently in line with the other exchanges and DFP politely accepting PreBid auction results. On her redirect, Wood took Isaacson’s graphic and handwrote an AdX box on it submitting bids to DFP. Then, in light of the other loopholes in Google’s behavioral remedy, she wrote box after box of other sources submitting bids to DFP from programmatic guarantees, private auctions, preferred deals, and so on.

Witness Two: Andrew Casale of Index Exchange

After this highlight came Andrew Casale’s testimony (questioned by David Geiger of DOJ). Casale is the CEO of Index Exchange, an ad exchange. He covered much of the same ground as Whitman, but focused on the ad exchange market instead of the publisher ad server market. He, too, thinks AdX needs to be divested from Google.

On cross examination, Karen Dunn spent considerable energy attempting to impeach him as a witness. Dunn does a lot of public speaking and communicating with business people, and he also testified during the liability phase of this adtech trial, so she had a lot of material to work with in hunting for inconsistencies. Her main focus seemed to be on his having initially said after the liability phase that he didn’t care whether AdX was divested, just that the ad exchange market should be fair and transparent. Now he wants divestiture, and in between, the idea came up that if AdX was divested, his company was a possible buyer and the choice of buyer would be up to the DOJ. Hard to say if Dunn could have made anything of it; his company’s not that plausible a buyer, and he wasn’t that set against divestiture before or so fervent for it now. But in any case, 6 o’clock arrived, he was flying to Canada tonight, and Judge Brinkema decided there wasn’t enough left to cover to keep him till tomorrow.

Dunn closed her cross-examination with a joke: “Your flight to Canada saved you from me!” And so ends day one.

I'm glad to see that Canada is acting as a refuge for good and noble people.