Day 12: Turnabout is Fair Play

In closing arguments, each side claims their remedy proposal is more effective, cautious, simple, and trustworthy, while Judge Brinkema keeps her eyes on the appeals clock.

Rhetorical reversals are a great American tradition. Thomas Paine’s famous revolutionary pamphlet “Common Sense” took its title from a British publication of the same name while inverting its arguments. Where the British accused Revolution-hungry Americans of regressing to a state of native savages, Paine turns around and argues that it is, instead, the British who are backwards-looking, while the Americans are at the cutting edge of civilization, focused on progress. Indeed, whereas the British traveled only for commerce and plunder, Americans traveled to forge connections for the benefit of humankind. Paine does it again in “Rights of Man,” responding to Edmund Burke’s defense of aristocracy with another reversal: it is the aristocrats who are too emotionally unstable to lead and the people who are naturally prudent and in touch with the real world. He wrote: “Mr. Burke talks of nobility; let him show what it is. The greatest characters the world have known, have risen on the democratic floor. Aristocracy has not been able to keep a proportionate pace with democracy. The artificial noble shrinks into a dwarf before the noble of nature.”

None of the parties at this week’s closing arguments for Google adtech remedies mentioned this heritage (although the DOJ did quote a different Founder—Ben Franklin—for his famous idiom “an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure”), but both put this rhetorical reversal technique into practice throughout the day, with respect to a variety of goals: effectiveness, caution, simplicity, trust, and time.

Effectiveness and Certainty

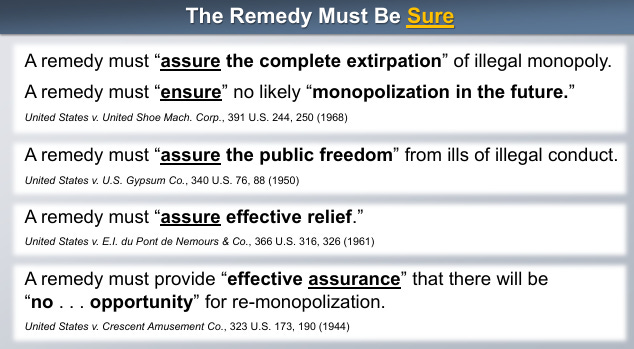

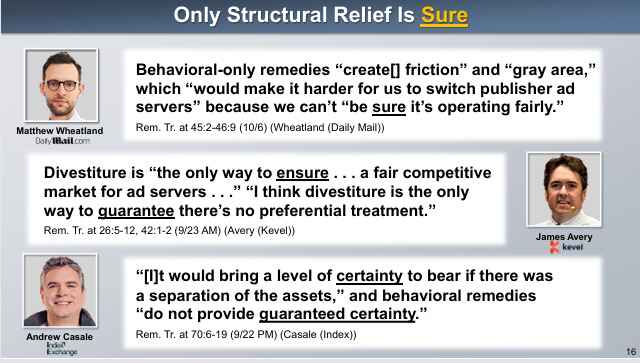

Beyond reprising it summary of the four remedy objectives noted during the opening statements of the remedy phase, the DOJ repeatedly emphasized that a minimum requirement for remedies is that they must be effective. Yes, the judge has discretion with respect to what the remedy will require of Google, but the judge should only choose between options that are effective. The DOJ pointed out that every witness (except for Google’s experts and last minute friendly-witness from WikiHow) agreed that only structural remedies would ensure effective and certain relief.

Google argued that, to the contrary, it is behavioral relief that is effective (unsurprisingly, quoting Professor Herbert Hovenkamp in support of that view). After all, Google said, every witness agreed that its proposal to integrate prebid into the auction process would yield competitive benefits and help level the playing field. And one advertiser, when asked whether divestiture would further improve competition more than prebid integration would, answered that it was “hard to say.” So why go beyond an effective behavioral remedy? Especially when there are so many questions about how divestiture would work. AdX has been integrated into Google for 17 years, and DOJ’s expert did not identify replacements for every software dependency. Moreover, Google argued—with more than a hint of chutzpah—if AdX is divested, Google could stop bidding on open-web display, and instead channel Google Ads transactions through YouTube. Thanks in part to Google’s own threat, it is structural relief that would be “messy and uncertain,” and ultimately ineffective.

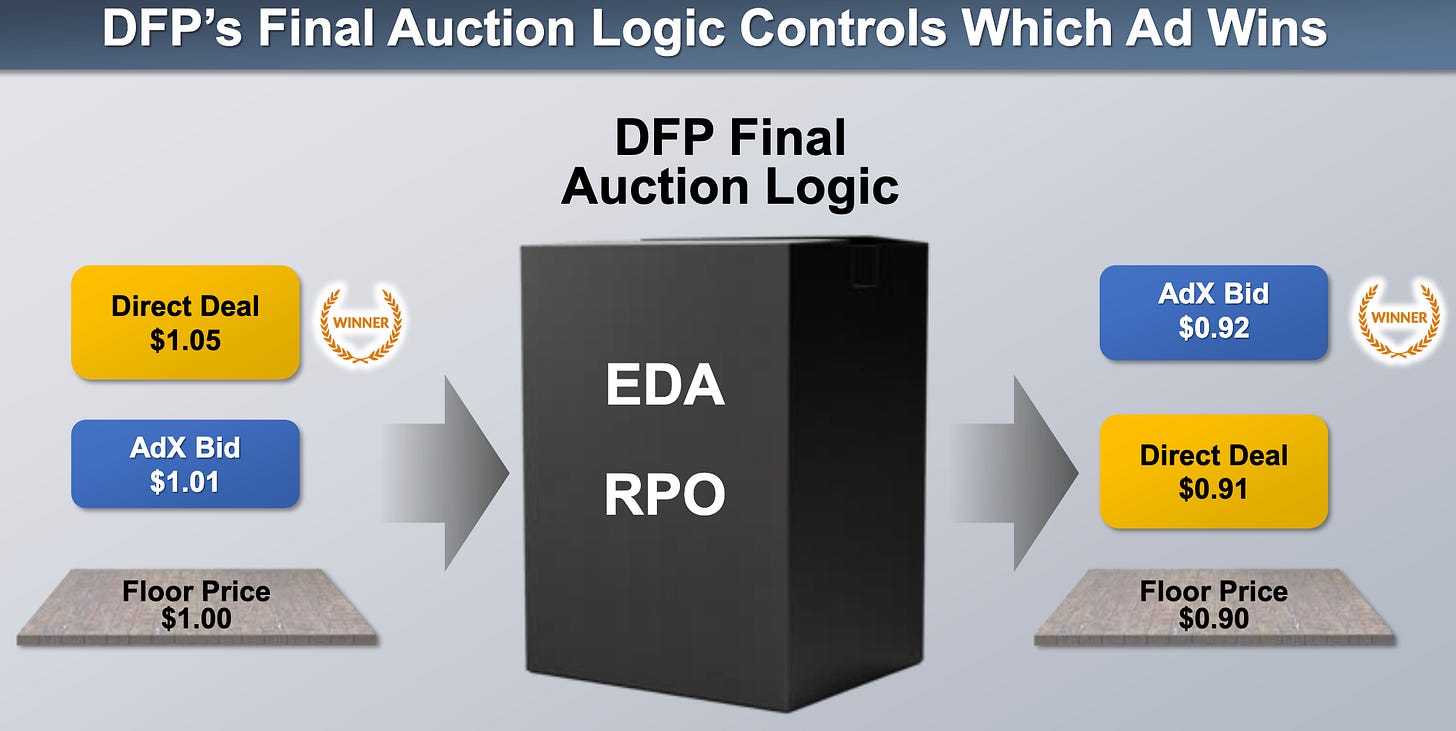

DOJ argued that although behavioral remedies could “slowly erode” monopoly power, they would not terminate illegally acquired monopolies. They would not fully restore a competitive market. Commercial software can be used to replace many dependencies and migrations are common projects in cloud environments, so divestiture is not uncertain. And Google’s prebid integration proposal would not change the fact that DFP’s final auction logic is a black box Google can manipulate. That’s why DFP’s final auction logic should be open-sourced, regardless of prebid integration.

Caution

One of Google’s favorite Supreme Court quotes reads like an homage to judicial cowardice: “When it comes to fashioning an antitrust remedy… caution is key,” and there should be “a healthy dose of judicial humility.” In Google’s view, practicing caution means that structural remedies should be a last resort. (Never mind that NCAA v. Alston did not concern structural remedies, and these statement were made in the course of rejecting the NCAA’s argument that a lower court’s limitations on how the NCAA could restrict universities from compensating athletes were too bold).

The DOJ argued that, here, caution actually favors structural remedies—which are ultimately clean and sure—over behavioral remedies that involve more judicial micromanagement. The same paragraph in Alston states that “[j]udges must remain aware that markets are often more effective than the heavy hand of judicial power...” Once a divestiture is complete, the DOJ argued, “natural market forces” will ensure effective competition. In context of case law conferring on courts the “solemn duty” of restoring competition, the DOJ believes Alston should be read to mean that remedies need to be strong enough to restore competition but simple enough to not require judges to engage in day-to-day oversight of detailed behavioral decrees. In other words, it is Google’s behavioral remedies that would improperly invoke “the heavy hand of judicial power.” Moreover, the American public should not have to bear the risks of behavioral remedies (if anyone should bear risk here, it is the wrongdoer—Google). The DOJ’s divestiture remedy—or Judge Brinkema’s hypothetical from the hearing about just shutting down AdX—would ultimately be simpler. And caution does not excuse a court’s duty of assuring that relief is effective. Not to mention that structural remedies have a history of unlocking benefits and creating new industries, as various AT&T remedies led to semiconductor chips and wireless phones.

Simplicity

One of several mid-20th Century Supreme Court cases the DOJ likes to invoke is U.S. v. Du Pont. And it’s easy to see why: there are some great quotes. “Divestiture has been called the most important of antitrust remedies. It is simple, relatively easy to administer, and sure,” that court wrote. It also found that “the public interest should not… depend upon the often cumbersome and time-consuming injunctive remedy, noting that “an injunction can hardly be detailed enough to cover in advance all the many fashions in which improper influence might manifest itself” and “the policing of an injunction would probably involve the courts and the Government in regulation of private affairs more deeply than the administration of a simple order of divestiture.” Thus, the “public is entitled to the surer, cleaner remedy of divestiture,” especially because “once the Government has successfully borne the considerable burden of establishing a violation of law, all doubts as to the remedy are to be resolved in its favor.”

But relying on hot quotes can backfire when the underlying facts are distinguishable. As Google pointed out, Du Pont was a merger case (Clayton Act Section 7) rather than a monopolization case (Sherman Act Section 2). While it’s reasonable to argue similar principles can support divestiture in both situations, courts sometimes do take that difference into account. And Google brandished another distinguishing point: the form of divestiture involved in Du Pont was a stock divestiture: Du Pont held 23% of General Motors Stock, and the remedy was to sell that off, rather than impose a bunch of complicated restrictions on voting rights and directors. *Of course* it was simple, easy, and sure to divest stock! But that doesn’t say much about divestitures of selling of business lines. The DOJ’s over-emphasis of Du Pont language is not fatal (the DOJ cites other cases that involved divestitures that require more legwork to effectuate technology and business unit separation) but it was a bit of an unforced error that Google exploited to argue that DOJ has a “disingenuous” pattern of cherry-picking quotes from distinguishable cases. Just as writers have to “kill their darlings,” sometimes litigators have to make tough choices to best serve their argument. That may not mean avoiding the quote altogether, but killing a slide, or at least defusing your opponent’s attack by anticipating it (“although Du Pont involved stock divestitures, other courts routinely…”). And at this stage of remedies, it seemed like Judge Brinkema was most interested in practical guidance, so was more likely interested in hearing about what other courts actually did in specific cases than in legal principles.

Another way DOJ argued that structural remedies are easy to administer was to invoke to Steves & Sons v. JELD-WEN (a 4th Circuit decision that is binding precedent in this district, in contrast to the Google search and Microsoft opinions, which are merely persuasive). Here, the DOJ did make a factual comparison: the Steves & Sons court did not require the victorious plaintiff to identify a particular divestiture buyer in advance before it ordered a divestiture. And the auction process ultimately led to a sale of the illegally acquired doorskin manufacturing plant, which was completed this year.

Google, in response, posed a hypothetical: what if a buyer hadn’t been found? The Steves & Sons court contemplated “revisiting” its order if no suitable buyer came forward. Going back to square one wouldn’t be simple, argued Google. And couldn’t finding a buyer for a massively-scaled complicated business like adtech be more difficult than finding a suitable buyer for a simple manufacturing plant? Moreover, the divestiture process allowed the defendant to challenge whether the particular buyer was in the public interest, further complicating and prolonging the process. (Indeed, JELD-WEN did challenge the choice of buyer as a way to relitigate and postpone divestiture, and even after completing the sale has filed yet another appeal—and under Gail Slater, the DOJ filed an amicus brief in support of the plaintiff).

Although the DOJ maintained that structural remedies are simpler than behavioral remedies (attempting to monitor whether Google is abusing latency rates is no easy task when hundreds of a second can make all the difference in online auctions, and Google has a demonstrated proclivity for making pretextual arguments about things like privacy and security if it is somehow caught disadvantaging competitors), the DOJ also urged the court not to sacrifice effectiveness for simplicity. The court should reject the idea that “purported technological complexity confers some sort of immunity to a remedy.” Other “would-be monopolists” are watching this case, and the court should not set a dangerous precedent that would embolden them.

Trust

Amidst the testimony of the hearing phase, Judge Brinkema telegraphed a degree of hesitation about whether it would be fair to craft remedies with the assumption that Google would try to violate them. Yes, there was extensive evidence that market participants did not trust Google, but could she really treat Google as a “recidivist monopolist”—per DOJ’s favorite turn of phrase—when there were no previous orders on remedies that Google had disobeyed in this case? It might be one thing if Google had a track record of disobeying her own court orders, but how could she legally rely upon things like alleged noncompliance far away in Europe?

At closing arguments, the DOJ pointed out that Google had repeatedly “tested boundaries” before this court, not only through arguments about privacy and safety that the court has dismissed as “pretextual” during the liability phase, and the introduction of a last-minute hearing witness based on a false pretext, but also the evidence spoliation campaign masterminded by Google executive Kent Walker. Google had a duty to preserve evidence but instead sought to hide and destroy evidence. Shouldn’t that weigh against trusting Google to comply with behavioral remedies that run counter to its economic incentives and involve a black box system that is hard to monitor? Google will “test every technicality, every punctuation mark.”

Moreover, trust wasn’t about procedural fairness towards Google. The real question was which remedy would instill sufficient business confidence among investors and competitors. Putting any subjective grievances against Google aside, would rational economic actors really invest and expand operations enough to restore competition if they “can’t believe there’s a new regime in place”? If Google-owned black boxes with economic incentives to self-preference Google products reduce certainty about whether the playing field is truly level? Why would publishers make the effort of switching?

Google, of course, parried with a different inversion. Putting aside whether Google was trustworthy (and it swears it is; Google promised to comply with remedies and amended its remedy proposal to address concerns raised in the hearing by offering to double the monitoring period from 3 to 6 years, and to provide more transparency to publishers about how auctions work), this was really about trust in the justice system itself. There would be a monitor, a technical committee, and ultimately Judge Brinkema herself to act as checks. Indeed, Google has two “swords of Damocles” hanging over it to ensure compliance: this court’s order and pending private adtech litigation too. Shouldn’t the remedies be written with the assumption the justice system works?

Time

The topic that was most pressing on Judge Brinkema’s mind, however, was time. She asked far fewer questions unusual, but the few she asked were about how soon remedies could take effect. “The evidence shows that time is of the essence,” she said, especially in fast-moving tech markets. “What I’m looking for from both sides today is how quickly remedies can go into effect.”

Although in previous hearings Judge Brinkema encouraged the parties to discuss settlement, she dispensed with that admonition today. She’s mindful that another court essentially adopted her rulings on liability issues in private adtech litigation against Google, and there are other pending cases. And she recognized that it’s “highly unlikely” that Google won’t appeal. Google will likely seek to stay (pause) remedies during appeal, and apart from that, remedies could get overturned. What’s the point of issuing a complex order with a monitor, she wondered aloud, if an appeal takes 2-4 years?

DOJ responded that there would be an AdX divestiture closing date within 15 months, and pointed out that we won’t have to wait until full timeline of structural remedies to start seeing a beneficial impact on competition. DOJ has vetted divestiture buyers hundreds of times and Google likewise has lots of M&A experience, so it is “hard to imagine parties” more sophisticated and prepared to do this. The due diligence process is “not irreversible,” so that could proceed in parallel with an appeal.

Google, for its part, bragged that it “pushed” its engineers to cut some behavioral timelines in half, so it can commit to achieving most remedies in 12 months, with a few outliers at 15 months. (DOJ later turned this around as well; if Google can push its engineers to complete behavioral remedies faster, can’t it push those engineers to complete the technical migration work of divestiture faster too?).

Judge Brinkema was pleased when the parties said they are close to agreeing upon a process for choosing a monitor and role of technical committee, which means that can move forward soon after decision since both parties propose some overlapping behavioral remedies (the DOJ’s behavioral remedies serve as interim relief while structural remedies are on the way, and also include a few measures—like requiring Google to share auction data and pay into an escrow fund to support the cost of publisher migrations—that complement divestiture but are not sufficient alone).

Google also invoked Judge Boasberg’s recent ruling in favor of Meta in the context of time, citing it for the proposition that the government must show monopoly power now (as in this instant; just let bygones be bygones for past misdeeds). Although FTC v. Meta was a liability decision, Google argued that recent declines in AdX market share (something like 56% to 42%?) in a shrinking market are new commercial realities that counsel against divestiture.

DOJ had another twist on time: behavioral remedies, it argued, are “inherently backward looking.” Structural remedies, by contrast, are “future proof.” They don’t require any particular view of how the market will change going forward. (And on that note, although Google says that artificial intelligence will transform the adtech market, DOJ argued that if anything, AI will entrench Google’s dominance, and pointed out that Google’s AI overviews are decreasing clickthrough rates for publishers. A neo- Paine-ian might argue that, far from being a noble guardian of the open-web, Google is an ignoble and extractive despot that must be de-throned for freedom to flourish).

Next Steps

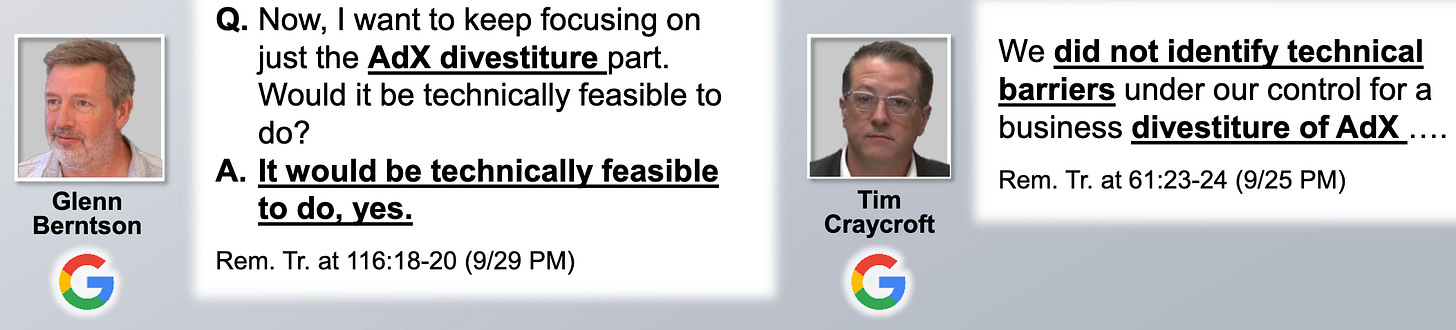

Judge Brinkema said that she expects that first phase of her decision will come out next year, although she has started pre-work on it already. That decision will address the core issue of whether to order structural remedies or not. She sounded slightly skeptical towards structural remedies in discussing her concerns about appeal timelines, but as always, listened attentively to the arguments. Google’s internal documents, which acknowledge that structural remedies of some sort are technically feasible, still loomed large at closing arguments. As the DOJ pointed out, it was only when getting up on the stand for the hearing that Google engineers began to claim that structural remedies were impossible or the most difficult project of their careers, not when communicating with each other candidly in contemporaneous emails.

Ultimately, Judge Brinkema will have to weigh effectiveness and certainty of remedies with her concerns about quick administrability.

After deciding whether to issue structural remedies, Judge Brinkema will issue a separate, more detailed order and figure out how to resolve differences about behavioral remedies. So it sounds like there could be another hearing in store on some of those details, much as Judge Mehta held a hearing about how to turn his general decision into a more specific order. And somewhere along the line, Google will fire off an appeal—while also battling states and private parties with similar claims. So closing arguments are not, yet, the end.

Further reading:

Thanks Laurel. Whether the legal system rules these monopolies as monopolies or not, and no matter how they treat them if are ruled as monopolies, I am most uncomfortable with 5 or 6 big tech companies/individuals controlling our country’s economy, media, space program,… Feels very scary!