Blurred lines: Who does Google compete with for ads?

On Day 15, an advertising agency executive explained how "purchase funnels" drive Google's power in digital advertising.

Is Google a monopolist in advertising? That’s a critical question in this case,1 but the answer hinges on how you define the relevant markets within advertising.

According to Google, it competes with all kinds of digital platforms like Facebook, TikTok, and Amazon in a broad market for digital advertising. If this theory is correct, Google’s market share in digital advertising is only 30% to 40% or so (and declining) — far lower than the share typically required to establish monopoly power.

The DOJ and States have proposed more narrow markets, though, arguing that there are relevant markets in general search text advertising, search advertising, and general search advertising. These market definitions exclude all potential competitors other than general search engines like Bing, so Google’s market share in these markets is correspondingly much higher — almost certainly high enough to satisfy the monopoly power requirement for Section 2 Sherman Act claims.

Earlier in the trial, we heard testimony from Google advertising executive Jerry Dischler, which advanced Google’s view of the digital advertising market. Dischler discussed Google’s competition with other huge platforms for a piece of the “digital advertising pie” and claimed that the “purchase funnel” concept that the DOJ has relied on is obsolete.

Today, we heard from someone who has frequently been on the other side of Google’s advertising auctions: Joshua Lowcock. Lowcock is the Global Chief Media Officer at a media agency called Universal McCann, where he is in charge of running digital advertising campaigns for various clients.

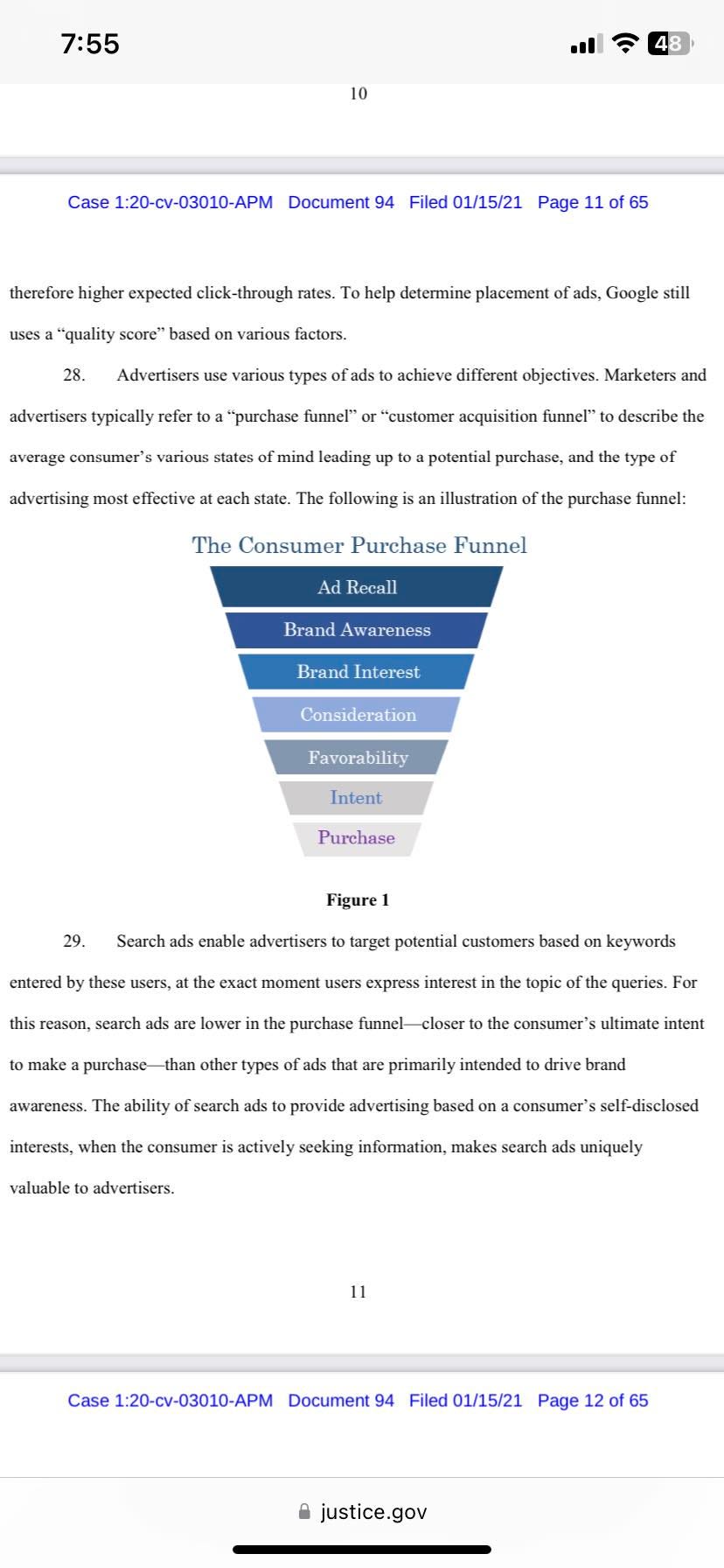

Lowcock’s testimony on direct examination from DOJ and the States painted a different picture of the digital advertising landscape than the one we heard from Dischler. According to Lowcock, search ads are “mandatory” in any advertising campaign — and he said he would not advise his clients to move their advertising spend to other kinds of digital even if the price of search ads increased by 5%. He further explained that the "purchase funnel” — the various states of mind that the average consumer experiences leading up to a potential purchase — continues to be a helpful construct that is used throughout the advertising industry.

The upshot of Lowcock’s testimony on direct examination was that search ads represent a uniquely valuable form of digital advertising because they target consumers when they are at the very bottom of the purchase funnel. That’s why he said that social media ads aren’t substitutable for search ads; ads on Facebook or Instagram are just less likely to hit users while they’re low down in the purchase funnel and ready to make a purchase.

If the picture wasn’t already hazy for Judge Mehta from Dischler’s conflicting testimony, Google further muddied the waters during its cross examination of Lowcock. Google’s cross pushed back against the purchase funnel construct, suggesting that today’s digital platforms have rendered the purchase funnel’s delineations much blurrier, if not entirely non-existent.

Lowcock didn’t back down from his testimony that search ads are not replaceable by other kinds of digital ads, but he acknowledged that ads on four different platforms — Google, Bing, YouTube, and Amazon — all promoted three different levels of the purchase funnel (awareness, consideration, and purchase).

Ultimately, the fact that there may be some competition between Google and non-general search engines for ads is not enough to defeat the market definitions proposed by DOJ and the States. That is to say that Google can’t prove digital advertising should be construed as a broad market just because a few companies moved ads over from Google to Facebook when Google raised its prices.

Instead, the true test of a relevant market is whether a hypothetical monopolist in the market could profitably impose a small but significant non-transitory increase in price. That’s likely why DOJ asked both Dischler and Lowcock about the effect of Google raising its ad prices by 5%. While both Dischler’s and Lowcock’s testimony seemed to imply that Google could profitably increase its search advertising prices by 5%, the admissions that Google elicited from Lowcock today illustrate the haziness of the digital advertising landscape. It will be up to Judge Mehta to sort out the mess.

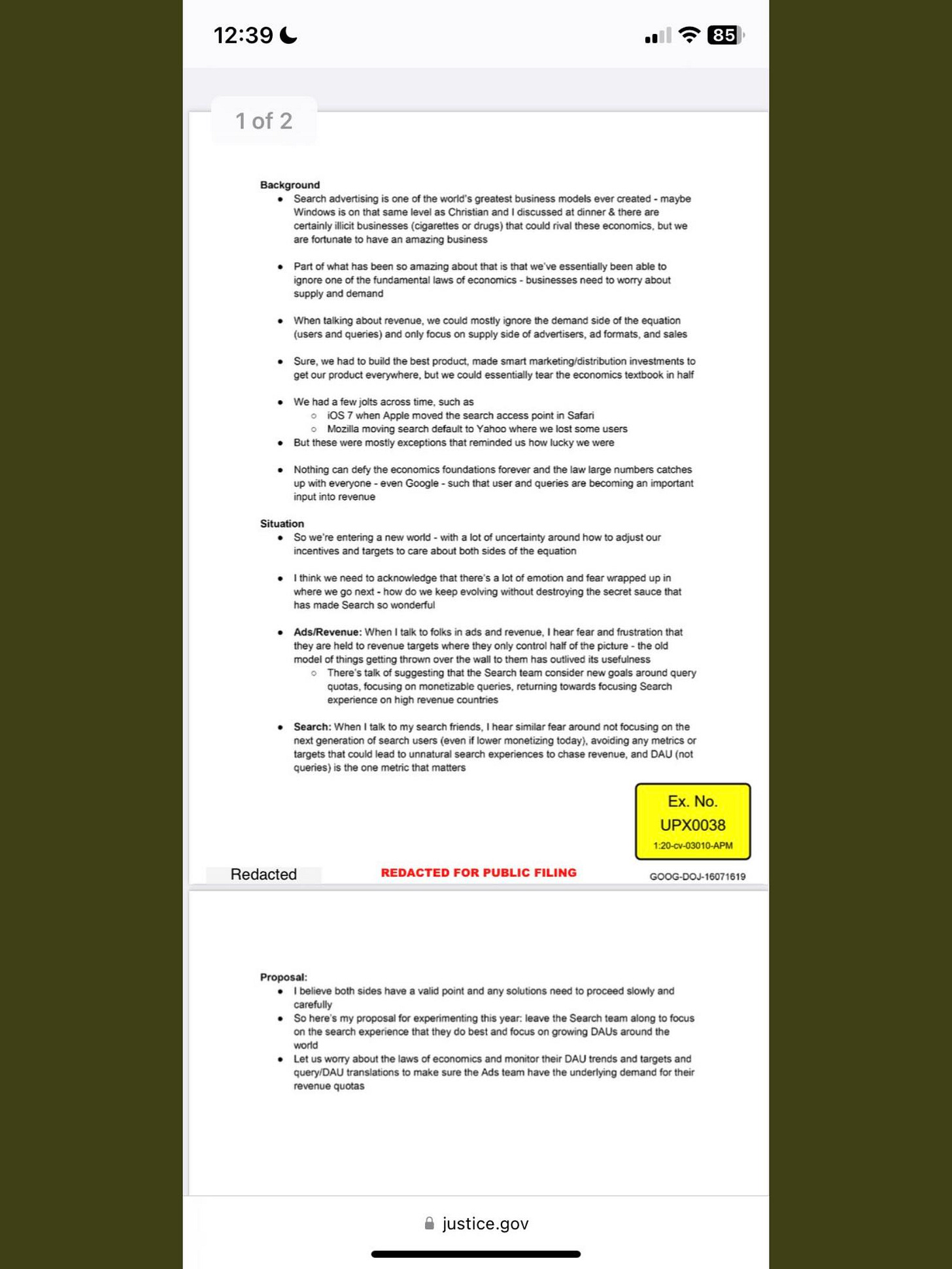

An update on the “embarrassing” document for Google

If you’ve been following the trial for the last few weeks, you might remember that the saga about DOJ publicly posting admitted exhibits on its websites started from what could have been just a simple hearsay objection; it became much more, however, when Google’s lawyer pointed out to Judge Mehta that admitting the document would lead to DOJ posting the exhibit and it getting picked up “far and wide.”

The argument about the document’s actual admissibility was temporarily shelved and DOJ ended up just using the document in a closed session with Google’s VP of Finance Mike Roszak. But Judge Mehta eventually admitted the document and ruled that the document was not confidential even if a bit embarrassing to Google. Judge Mehta made this ruling over the arguments of Google’s counsel that the document’s statements were hyperbolic and meant to cosplay Gordon Gekko as part of a training on public speaking.

Judge Mehta also ruled that he would unseal the closed-session testimony about the document. I’m still waiting to see that unsealed testimony, so we don’t have the full context for the document yet — but we do now have the document as the DOJ posted it on its website at the end of last week. I’ll try to follow up with another update to contextualize the document once the testimony has been unsealed, but for now, you can take a look at the document itself.

It’s hard to evaluate the weight and significance of this document without the accompanying testimony, but it’s now at least clear why Google fought to keep this out of the public eye.

That’s all I have for now. Today we also got to hear the beginning of testimony from a Google VP about its advertising auctions — the “best way to spend an afternoon,” according to the DOJ lawyer — but we’ll hear a lot more about this tomorrow.

Recall, though, that monopoly power isn’t enough by itself to establish Google’s liability. Google must also have illegally acquired or maintained that monopoly power through “exclusionary conduct.”

"We could mostly ignore the demand side of Economics"

That's a really incriminating line admitting monopoly power right there.

"Google’s market share in digital advertising is only 30% to 40% or so (and declining) — far lower than the share typically required to establish monopoly power."

What is the rationale for these percentages?

I imagine a world in which only small and medium sized companies exist. In such a world 5% would be already gigantic.