Between the Lines of Google Ad Tech's Closing Arguments

Ending the "best-tried case" she's heard in years, Judge Brinkema reveals her thoughts on a key area of law, and it's not looking great for Google.

Happy Thanksgiving. This year, we’re thankful for the leadership at the Justice Department and Federal Trade Commission who have mightily reinvigorated Sherman Act Section 2 jurisprudence, proving that a law from 1890 can ensure fair and democratic markets today, tomorrow, and beyond.

This piece was written by Laurel Kilgour, Research Manager at the American Economic Liberties Project, who attended closing arguments earlier this week. I did some light editing. Let’s jump right in.

“Oyez, oyez. All persons with business before the court draw nigh.”

So began the last day of the antitrust trial targeting Google’s ad tech empire. Judge Leonie Brinkema was not wearing a powdered wig, but her snow-white hair, tucked into a neat bun and sneaking out in wispy tufts behind her ears, could be mistaken for one if you squinted just right from the packed back benches of the federal courtroom in Alexandria, Virginia. On this chilly late Fall day, she wore a red turtleneck under her black robes.

The evidentiary portion of the trial was long over. As copiously documented by Big Tech on Trial, over three weeks in September, the parties put their best foot forward on direct, grilled hostile witnesses, and entered hundreds if not thousands of exhibits into the record. The trial had been chopped in half from the expected six weeks by Brinkema’s relentless slashing of duplicative testimony (they don’t call the Eastern District of Virginia the “rocket docket” for nothing).

Why not schedule closing arguments immediately afterwards, as some courts do? During the long gap, the parties drafted extensive summaries of their versions of the facts and the legal conclusions that should be drawn about the case. These filings, which are hundreds of pages long, contain meticulous pinpoint citations to every relevant page number of every exhibit, and every relevant line number of the trial transcript for each witness. For several weeks leading up to the closing arguments, Brinkema (and her clerks) had the opportunity to review these tomes and come up with questions she might want to ask.

Although lead counsel for the parties were able to spend the bulk of their respective ninety minutes marching through their remarks as planned, 80-year old Brinkema came ready to interject with Socratic questions to test the logic of the zealous advocates before her — as well as to check her own nascent inclinations about how to rule in the case. (“Whether I do a lot of interrupting,” she counseled in advance, “depends on how you argue the case.”)

The Justice Department’s Closing Argument

The DOJ split its time into an hour long opening statement, with the remainder reserved for rebuttal. The DOJ also split this time among two different attorneys. Clean-cut and confident in a standard black suit, Aaron Teitelbaum handled the opening statement. His voice was strong and controlled. He was more comfortable sticking to his plan than nimbly pivoting to address questions (“I was going to get to that”) but he regrouped pretty well the few times Brinkema interjected.

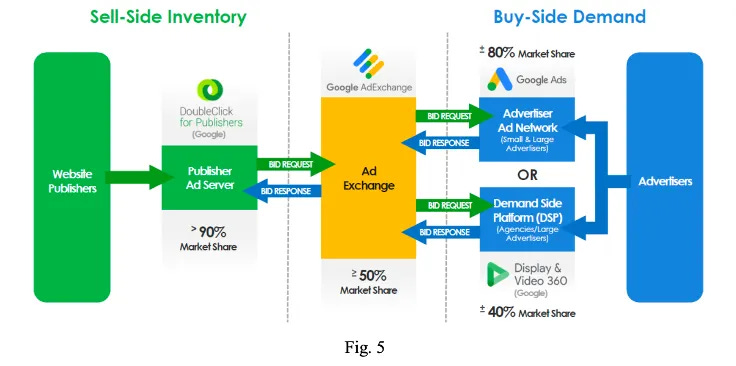

Teitelbaum began with a declaration that for well over a decade, Google has “rigged the rules” of the ad tech market and made acquisitions to “extinguish competition.” Why have advertisers and publishers continued to use Google’s ad tech products? Because Google is “once, twice, three times a monopolist” in the (1) publisher ad server market, the (2) ad exchange market, and the (3) ad network market (see the below image for a review of where these markets sit on the chain.) Customers had “no realistic alternatives.” Teitelbaum showed a slide of the now-infamous document where a Google analogized Google’s adtech empire to Goldman Sachs owning the New York Stock Exchange.

Teitelbaum then honed in on a key difference in how the parties presented their cases, noting “all evidence is not created equal.” The DOJ presented a variety of industry witnesses who lived and breathed monopoly-dominated market realities every day. By contrast, all but one of Google’s witnesses either a) worked for Google or b) were otherwise paid by Google to offer sympathetic testimony. The one exception? A civil servant from the U.S. Census Bureau who does not use the ad tech tools at issue in the case.

Teitelbaum emphasized that “there is no one true market definition that the court has to divine from the ether,” citing case law to explain that market definition is just a legal tool to get a sense of the “arena in which significant substitution occurs.” It does not matter whether Google views Facebook as a competitor in some wider marketplace; the case law on market definition expressly acknowledges that the existence of possible broad markets does not negate the existence of narrower sub-markets. Furthermore, “There is no dispute that Facebook and TikTok ad tools cannot be used for open web display advertising.” They can only be used within their own walled gardens. Thus they are not reasonable substitutes for Google’s publisher ad server, DoubleClick for Publishers (DFP). Relevant competitors in this case are those who compete for open web display advertising. Teitelbaum refuted Google’s suggestion that open web display is a “made for litigation” market by noting that third parties and Google’s own internal documents reflect that open web display is indeed a distinct market.

Brinkema jumped in a few times. At one point, she questioned whether she needed to resolve one core dispute between the parties: Can Google’s ad tech products reasonably be divided into three separate markets (servers, exchanges, networks) as DOJ argues, or are they all one integrated ad tech stack, as Google argues? This decision could be sidestepped, she hinted, if she ruled based on direct evidence that Google’s customers feel trapped, and that Google knows it is free to degrade their experience without consequence thanks to its market power.

Brinkema wryly noted that in the Google Search case, Judge Mehta “punted” on deciding a separate issue. I don’t think Brinkema is a “punter” by temperament, and it’s more likely she’ll rule on the core dispute. But the question does suggest that she views the direct evidence in the case as persuasive. (Direct evidence included publishers testifying that they felt “stuck” with Google’s publisher ad server even when Google degraded product quality, or internal documents where Google employees candidly admit that it would take an “act of God” for customers to switch ad servers; or testimony that even deep-pocketed Facebook found it “infeasible” to compete with Google in open web display. Tellingly, AdX’s take rate stayed flat at 20%, despite Facebook’s entry and exit from web display.) Indeed, even with 56% market share, AdX was dominant because the next biggest competitor had a 6% market share– and AdX’s share was almost twice that of all other competitors combined.

Turning to Google’s conduct, Teitelbaum focused on two ultimatums Google gives to customers: 1) If you want to access Google Ads unique demand, you must use AdX; and 2) If you want real time access, you must use DFP. He showed an internal email where a Google executive wrote: “Our goal should be all or nothing — use AdX as your SSP or don’t get access to our demand.”

Another manifestation of Google’s market power was its decision to impose Unified Pricing Rules (UPR) on its publisher customers. UPR removed the ability for publishers to set different price floors for different ad exchanges or advertiser buying tools. Before Google took away this ability, publishers often set higher floors for AdX to reduce their dependence on Google by shifting some transactions to rival ad exchanges and advertiser ad networks (an internal Google document recognized that publishers wanted “revenue diversity”). Although Google argued that this restriction was better because it was “simpler,” Teitelbaum argued that it was just another way of saying “Google knows best.” But the antitrust laws say: “Competition knows best. Freedom of choice knows best.” Those are the goals. “Simplicity is not the goal in and of itself” and does not justify Google’s abuse of its monopoly power, as Teitelbaum explained.

Similarly, at trial, Google expert Dr. Mark Israel suggested that integration of the server, exchange, and network into one stack was itself a pro-competitive benefit. But on cross, he admitted that he did not quantify that opinion in any way. Judge Brinkema asked: “Would you agree that if there were evidence of advantages from integration, that would be relevant?” Teitelbaum pointed out that Google bears the burden of showing that pro-competitive benefits are large enough to outweigh any harms to competition.

Brinkema pressed on: “What if a company built the best widget that customers would pay any price for?” Teitelbaum parried: “Google didn’t do that; instead they forced people to buy a widget they don’t even like.”

Teitelbaum wrapped up his statement by dispelling myths: The DOJ did not sue Google “because of its size” and was not here to “make the court do central planning.” The point is to “hold Google to account for rapacious, anti-competitive conduct” stretching back over a decade – conduct that has hurt innovation and led to higher prices.

Google’s Closing Argument

After a fifteen minute break, Google lawyer Karen Dunn stood up. Dunn is a petite woman — not much over five feet fall, even in two-inch pumps — with short hair corkscrewed into tight curls. She wore not only a standard black pantsuit, but a black blouse as well, and equally unassuming accessories: round pearl earrings and sensible glasses. She spoke quickly and confidently.

The substance of Dunn’s argument was anything but unassuming. She painted a vastly different picture of the state of the ad industry and Google’s role within it. Going up against Facebook and TikTok, Google found the industry fiercely competitive. And overall trends within that broad industry showed falling prices and increased ad inventory volumes over time, reflecting industry-wide growth.

In her very first lines, she warned the court that ruling against Google would require “overruling Supreme Court precedent,” particularly AmEx and Trinko. Together, these cases show that the “law protects integrated platforms,” out of recognition that “network effects fuel economic growth.” The antitrust laws were designed to stop price increases and other harms. “What happens when prices go down, but innovation goes up?” That scenario — what Google claims describes ad markets — is what the laws are supposed to encourage.

During the DOJ’s opening statement, Teitelbaum had distinguished Trinko on its facts: In that case, Verizon unilaterally refused to build infrastructure to connect to rivals. None of the conduct involved was customer facing. No court has adopted a doctrine endorsing refusals to deal with customers; other post-Trinko cases have focused on refusals to deal with rivals as Trinko did.

Moreover, Google’s expansive interpretation would essentially legalize “tying” (review BTOT’s analysis of tying in this case) because, “as a matter of semantics,” it would be easy to reframe such conduct as a unilateral refusal to deal. In addition, Trinko itself noted that the Court would have viewed the conduct at issue differently if it were motivated by “anticompetitive malice.” Teitelbaum displayed several slides chock full of quotes from Google employees that “say the quiet part out loud” by revealing the true intentions behind Google’s conduct: insulating itself from competition, not serving customers better or protecting them from cybersecurity threats. (On the latter point, Google’s own research found that the click-spam rates of third party exchanges were at “acceptable levels” that were “comparable to AdX”). One Googler wrote: “Somebody will become the OS [Operating System] for Display. We want it to be us.”

Dunn emphasized that Justice Gorsuch, back when he served as a Tenth Circuit judge, wrote an opinion arguing that “[i]f the law were to make a habit of forcing monopolists to help competitors,” that would deter the monopolist from innovating and smaller companies would then “just demand the right to piggyback on its larger rival.” (One challenge with relying on this opinion is that, like Trinko, the facts concerned refusal to deal with rivals, and Gorsuch acknowledges that tying which harms consumers violates the antitrust laws).

Dunn framed Google as a good corporate citizen by emphasizing that although Google did not believe it was required to do so under the law, Google had spent “countless hours” working to make its products interoperable. The problem, as Dunn described it, was that Google’s customers demanded too much — one even testified that software should be “community property.” (This alluded to a theme Google has been pounding hard in other cases; that any substantive court-ordered change to its conduct or corporate structure is tantamount to Communist “central planning.” Dunn’s reference to this theme was more subtle and restrained than the rhetoric of Google’s counsel in a remedies hearing earlier this year after Google’s jury trial loss to video game company Epic over Google’s app store monopoly).

Dunn framed much of Google’s conduct — such as “First Look” in auctions — as beneficial “innovation” in response to competition. One Google witness had testified that dynamic allocation, for example, made ad inventory 136% more valuable. Innovation! Google pursued a “competitive response” to Header Bidding by developing “Open Bidding.” Innovation! As Teitelbaum anticipated, Dunn also emphasized choices that Google offers customers in various markets. For example, some customers use Google Ads, some use DV360, and some multi-home. As for DOJ’s complaint that Google should have developed Unified First Price Auction earlier, Dunn said: “They don’t say when” Google should have done that. “That’s not how innovation works; the past lays the foundation for the future.”

In Google’s story, Google’s innovations benefit either advertisers, or publishers, or both. But it’s just as easy to argue that Google’s innovations also benefit… Google. In Judge Mehta’s Opinion in the Google Search case, he determined that Google’s ad innovations sought to benefit advertisers and users (see p. 85, Par. 247) But, quoting Microsoft, “[B]ecause innovation can increase an already dominant market share and further delay the emergence of competition, even monopolists have reason to invest in R&D.” And Judge Mehta held Google liable in that case, despite Google’s product innovation. Is this de ja vu?

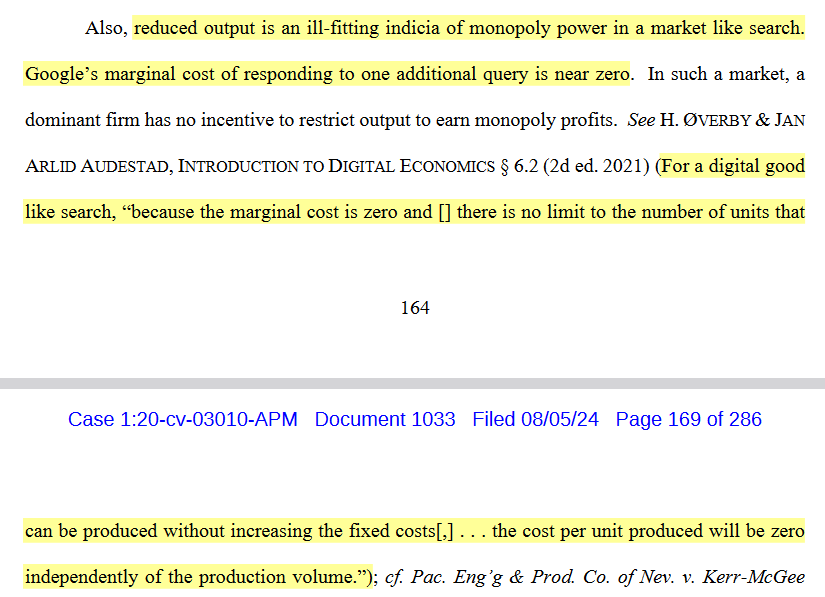

Moving on, Google, according to Dunn, did not enjoy monopoly profits. Instead it has taken only a “small share of the exponential growth” of the advertising industry. Meanwhile, over time, ad tech fees as a percent of ad spend have fallen, prices have fallen (lower cost per click), ads perform better (increasing clickthrough rates), and quality has improved. This is an increase in output; not the restriction in output antitrust law warns about. Accordingly, the DOJ “cannot make the exceptional case for government interference” in this market.

By comparison, look how Judge Mehta dealt with Google’s argument that Search had seen increased output (i.e., an increased number of search queries):

Both Microsoft and Google Search were cases in which increased output did not inoculate the monopolist from liability. Dunn did not seem to account for or distinguish Google’s alleged monopoly power in the ad tech case.

Dunn was just warming up to a firm sense of righteousness when she turned to a slide declaring that DOJ’s case is “built on cherry-picked statements.” That now-infamous quote from the engineer who likened Google’s ad stack to Goldman Sachs owning the NYSE? He testified on the stand that was just the “late night jetlagged rambling” of a newbie at Google who was in over his head. Other emails were just the opinions of individual employees about things that might not even be implemented. They did not reflect Google’s actual intentions.

But this line of argument earned a rebuke from Brinkema. Under the direction of Google’s then-General Counsel Kent Walker, Google had hidden or destroyed several years’ worth of evidence, in part by coaching employees to copy lawyers on ordinary business communications to shield them from discovery, and in part by making “history off” the default setting on all chat messages– even when Google had formal obligations to preserve all evidence during litigation. Two other federal judges have already expressed shock over this unethical conduct. Although Brinkema has not announced how this will formally impact her decision, it was clear that Dunn had overstepped with her argument about Google’s true intentions.

“You’re getting into dangerous territory when you talk about what Google’s thinking was. We don’t know,” Brinkema said.

Dunn was not rattled, but also did not have much of a response. Other things, such as witnesses and data, she said, “show the full context” of what Google was thinking. “I won’t belabor this… Moving on…”

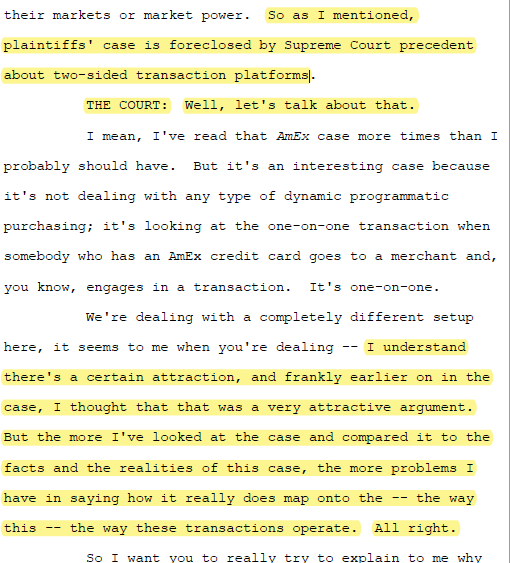

But the most revealing exchange was about to come. Big Tech on Trial talked about Ohio v. Am. Express in the context of the Google Search case, but it’s just as relevant — if not more so — to one of the central issues in this case: Whether Google’s ad tech stack is a single two-sided market, or three separate markets bundled together. If it’s just a single market, and a single multi-sided transaction, AmEx suggests that pro-competitive benefits on one side of the exchange will offset anticompetitive effects on the other side of the transaction. But if we’re looking at three separate markets, as DOJ alleges, then the tying claim becomes much more apparent.

Brinkema seemed skeptical that AmEx applied. Here’s the exchange that has Google’s lawyers up at night:

Dunn responded that in both the credit card industry and the ad display industry, the point is to facilitate a transaction between a buyer and a seller. The “animating feature” of Amex is that you can’t look at only one side of a two-sided market. In her view, all of Google’s ad tools are ultimately about facilitating a match in a two-sided market.

Moreover, Microsoft’s advertising ecosystem looks like Google’s. Google was competing with one of the largest companies in the world, whose ecosystem is not only similar but has more advantages– like being able to place ads on Netflix. The subtext was: so why was the government picking on Google, the underdog?

In any event, new technologies– such as supply path optimization — show that the display advertising landscape is constantly evolving. Thus, the historical categories the DOJ is so fixated on — advertiser ad networks, ad exchanges, and publisher ad servers– no longer reflect the dynamics of the industry. And because some display ad spending is “substituted” to TV or social media instead, the market should be defined to encompass broader categories– which leave Google with a very small market share. Similarly, some Google internal documents express concern that Amazon’s “suite of ad solutions increasingly encroaches upon Google’s core business.” Thus, Amazon should not be “gerrymandered out” of the market definition.

When Dunn returned to the theme of customer choice, Brinkema interjected: “Isn’t the evidence that publishers felt so locked in, evidence that there’s unique demand” for Google Ads that Google only gives access to through tying?

Dunn stuttered a bit, but settled on arguing: “The truth is, publishers have access to Google Ad demand in other ways — Ad Sense, etc.… We’re not here to argue that there aren’t small groups of publishers, like News Corp., that are unhappy they can’t access the demand in the precise way they want.” But they don’t get tools as “community property.” Antitrust law does not require Google to share real-time bidding or customer base information. Again, the insinuation is that by enforcing the antitrust laws, the government is engaging in an anti-capitalist project of central planning.

Eventually, Brinkema gave a five minute warning. Dunn asked the court for “a little bit of grace” on that, but Brinkema stayed firm: “five minutes.”

Dunn skipped over many slides, and ultimately settled on a chart comparing the market share of other major monopolists (e.g. Standard Oil: 75%) to the mere 10% share of spending Google allegedly had out of a broad display market that included things like social media. Brinkema asked whether Dunn had a similar chart based on the DOJ’s market definition, and Dunn said she didn’t because there was “no data for that” because “nobody thinks of the market that way.” (Editor’s note: Nobody except all of the market participants who testified in the Justice Department’s case, or the Google employees who acknowledged the existence of distinct markets in their own internal discussions!)

The Justice Department’s Rebuttal

Soon after Dunn stepped down, a different DOJ attorney rose to her feet to wrap up the day. Julia Tarver Wood struck a contrast with both of her black-suited predecessors by wearing a… muted plum colored pantsuit and a white blouse. But that small distinction was amplified by her presentation style, which was likely honed in jury trials. The only lawyer to speak with a twang, her voice boasted a much broader range of storytelling inflection than either Teitelbaum or Dunn. She was also the only one to really leverage the power of body language– at one point taking a big step backwards and holding her arms wide to make a dramatic point.

Although Dunn had raised a flurry of statistics and raced through many slides, Wood refrained from trying to chase down every technical quibble. She started where Brinkema’s question left off: how would Google’s market share look compared to legendary monopolists such as Standard Oil? Wood explained that DOJ’s expert, Professor Lee, had looked at “terabytes” of “log level data” to calculate extremely high market shares, north of 80 or 90% for ad servers and ad networks, and a fairly high range of 50-60% for ad exchanges as well.

Listening to Google’s vision of a fiercely competitive, beneficial market reminded Wood of the Charles Dickens novel, A Tale of Two Cities. One tale was told by real market participants who live and breath these markets, and were not paid to testify. Another tale was told by Google’s witnesses– and again, she reminded the court, that all but one of Google’s witnesses were paid in one way or another by Google.

Piling on the historical analogies, Wood paraphrased the testimony of Google’s expert, Dr. Mark Israel as “Let them eat cake!” All publishers would need to do is build their own hundred million dollar ad exchange. They would just have to “work harder” to sell directly. But the court should not heed that expert testimony, because the court heard from the market participants themselves how challenging that would be: “It ain’t so simple.”

As for Google’s argument that output expansion disproved antitrust liability, Wood explained that major monopolization cases such as Standard Oil and AT&T “all involved thriving markets” but that did not stop courts from holding the monopolists liable for their anticompetitive conduct. The “general growth of the internet tells us little” about the specific markets at issue in this case. Google failed to show that rivals such as Amazon or TikTok offered competitive solutions outside their own “walled gardens.”

Although other players came up with “industry contrived hacks” such as header bidding to get around Google’s monopolies, ultimately they did not “disintermediate” Google: “All roads lead back to Google at the end of the day.” Although one witness described the market after header bidding as “hypercompetitive,” that was only relative to the previous waterfall system, which was not competitive at all. And in any event, every web display ad through header bidding is included in DOJ’s market definition.

Wood then posed a series of rhetorical questions: Was it “fierce competition” that held back publishers from switching? Was it “fierce competition” that allowed UPR to restrict the ability of customers to choose who to work with? Google’s own employees clearly understood Google’s reputation as an “authoritarian intermediary” in the market.

As for AmEx, while ad exchanges for open-web display advertising are two-sided transaction platforms, Google’s argument falls short when it tries to tack on publisher ad servers and advertiser ad networks. Those each sell services only to publishers or only to advertisers, and do not require that “both simultaneously choose to use” the tool. That lack of simultaneity distinguishes this case from AmEx.

Brinkema broke in with a time warning: “You opened with Dickens; a story that involves a guillotine. Well, I have one, and I’m about to use it.” (The courtroom laughed).

Judge Brinkema closed on a note of professional gratitude: "This is the best-tried case I've heard on the bench in years. Counsel for both sides were well prepared and incredibly courteous" despite very different views. It was "a pleasure."

Or rather, she tried to close.

But Karen Dunn wasn't ready to be done.

Brinkema noticed Dunn starting to stand.

Dunn began: “We have one cite that's directly on point to your question earlier…”

Brinkema responded calmly but firmly: "No, we're done. We've got thousands of pages."

Brinkema left the courtroom. Dunn hugged Wood and shook hands with Teitelbaum. Attorneys and staff picked up binders and powered down computers.

Dozens of people waited in line for a handful of elevators, walked back past security, and under the statue of a blinded Lady Justice and a pedestal inscribed “Justice Delayed, Justice Denied.”

Brinkema has no set deadline for her decision, but expects to issue one early next year. If she finds Google liable for monopolization or restraint of trade, there will be separate remedies proceedings, likely next Spring.

Great read. Thank you so much for this exceptional coverage.

Happy Thanksgiving to Matt, Lee, and Laurel, as well as to all Big readers!