Will A Court Really Take Away Google's Monopoly? The Antitrust Remedy Phase Starts.

Judge Amit Mehta held the first day of hearings on how to cure Google's illegal monopoly power. The government made a strong showing, while Google barely admitted it was found to have violated the law

Welcome to day one of the Google search remedy phase in the D.C. district court, which should last for about three weeks. I’m writing this from a crowded hallway surrounded by a lot of well-dressed people, smelling of law and money. There are a bunch of business reporters here as well, as two floors down is the Meta antitrust trial.

It’s truly an overwhelming and historic amount of litigation to write about, two companies worth more than a trillion dollars on trial over their business practices. At Big Tech on Trial, we only have enough resources to cover one trial at a time. We’ve chosen Meta. But we can’t let Google’s remedy go totally unremarked, so today I attended and will highlight the main issues involved in the remedy phase.

First, some context. The trial is split into two, the first is the liability phase about whether what Google did is illegal. Last year Judge Amit Mehta ruled that the search giant is an illegal monopolist, so this next part of the trial is about what to do to cure the monopoly. After his ruling on liability, Mehta laid out the next steps.

The Antitrust Division had to put forward a proposal on remedies that would cure the unlawful monopolization. In it, they requested an end to the exclusive contracts Google has with Apple, Verizon, Samsung, Mozilla et al, no more payments for distribution, divestment of Chrome, and restrictions and potential divestment of Android, as well as limits on Google’s investment in generative AI firms and products. In addition, Google would have to share data with rivals, and syndicate its search results. The idea behind this proposal was to allow entrants into the search market, eliminate Google’s head start in search, prevent monopolization of generative artificial intelligence, and return some power to publishers.

After its initial proposal, the Antitrust Division did 58 deposition interviews with industry participants, and looked through tens of thousands of documents. With this information, it made some modifications to its proposal, mostly by relaxing its call for restrictions on generative AI products. And that’s the revised proposal that the court heard today. (It’s worth noting that Trump won the election in the interim, but the remedy is pretty similar to the one Biden put forward.)

And what about Google? Well Google started its approach by not acknowledging the legitimacy of the court decision on liability. The company said, “We strongly disagree with and will appeal the decision in the Department of Justice's (DOJ) search distribution lawsuit.” Still, given it’s a legal requirement, Google made its own proposal on how to cure the monopoly it says it doesn’t have. The company suggested that it alter its contracts with distributors like Apple to disallow exclusive agreements. Browser companies could still accept payments from Google, but would be allowed to have “multiple default agreements across different platforms,” and change their default browser every 12 months. No data sharing. No syndication. Little on generative AI. No spinoffs. Basically, like the scene in the Godfather, Google said, “My offer is this: nothing.”

Ok, with that, let’s run down the day. It started with the Antitrust Division’s lead attorney on the case, David Dahlquist, laying out the basic remedy proposal put forward by the government. In Dahlquist’s opening, he frequently referred back to Mehta’s decision, reminding the court that yes, Google is a monopolist that violated the law.

On substance, the main new question is to what extent generative artificial intelligence should factor into any remedy. Remember, the liability part of the case was not about generative artificial intelligence, it was about how Google maintained its monopoly in search and search ads through unfair business methods, most notably its agreement with Apple and other distributors to pay them not to allow rival search engines to compete for the default slot in their browsers. Yet, even though Google doesn’t have a monopoly in generative artificial intelligence, and it wasn’t really a question when the was brought in 2020, AI is the next inflection point for the internet. One possibility is that we are transitioning to a world of chatbots with integrated search. What will that look like? Well we an already sort of see it. When you do a Google search now and you get a written answer below the prompt, it’s a new product called Google AI Overview.

Historically, antitrust remedies are most successful at just such moments, allowing a new market to be competitive instead of dominated by a legacy incumbent. It makes no sense to leave generative artificial intelligence out of the remedy, as Google has built its products for AI on top of its search data, and remedies must ‘forward-looking.’ Yet, it’s not a monopoly in large language models.So the question is how to make the remedy forward-looking while also recognizing that there are lots of players in that space, from Grok to OpenAI to Anthropic to Perplexity. Sure Google shouldn’t benefit from the illegal fruits of monopoly, aka the data and advertising infrastructure it illicitly garnered, but what exactly does that mean?

Aside from the substantive practical question, a key legal point of dispute is how causally connected the remedy has to be with the original behavior that facilitated the unlawful monopolization. The DOJ thinks the judge should terminate the monopoly, that the specific moats built by Google using unlawful behavior must be taken apart. Google thinks the judge should only stop the narrow bad behavior explicitly proved at trial, while leaving the fruits of its monopoly, which it says it garnered almost entirely through lawful means, alone. The case law is mostly on the Antitrust Division’s side, but the last real break-up was AT&T in 1982, more than 40 years ago. The Microsoft decision in 2001 is a little more ambiguous.

Some notes from Dahlquist’s opening, which I found strong except for one point.

In response to a question from Judge Mehta, Dahlquist said that Google has already revised its distribution agreements to remove the exclusivity provisions, which is news.

An OpenAI official and Perplexity's co-founder will testify on how Google’s distribution power hinders them from fairly competing.

Judge Mehta asked if spinning off Chrome is a 'structural remedy' or a ‘behavioral remedy,’ and if that requires a higher burden than a behavioral remedy. Dahlquist said yes to question one, then grudgingly conceded a modest yes to question two, pointing at page 106 of the Microsoft decision in 2001. This concession strikes me as a mistake, since there’s really no difference between a structural and behavior remedy, and the case law is not clear.

Judge Mehta was focused on process questions around the law, which means he’s thinking about what he’s allowed to do for remedies. That’s a good sign for DOJ. He asks if the data remedies, such as search and ad syndication, are they behavioral or structural remedies? Google argues they are, DOJ says they are not.

Another witness coming to trial is David Locala– former Global Head of Technology M&A at Citi and former Co-head of Technology M&A at Deutsche Bank, who will talk about how to spin off Chrome. Locala has 20 spinoffs in technology under his belt. Google, DOJ says, under-invests in Chrome despite it bringing in billions in profit. A different expert, Dr. James Mickens, will testify about the technical feasibility of divesting Chrome.

DOJ can't get Google distribution partners to testify publicly because they are afraid of retaliation. Urges an anti-circumvention provision in the remedy. In addition, DOJ calls for a technical committee, which for some reason Google calls a 'due process' violation.

Judge Mehta asks whether contracts for non-Google AI chatbots can incorporate Google search. DOJ lawyer points out that a draft Android GenAI contract - currently on hold - is a virtually identical exclusivity arrangement to the ones at issue.

National security arguments from Google are irrelevant, since courts have traditionally deferred to the executive branch and not private parties on the matter. (This statement worries me, because it means Trump can just settle the case on the grounds of national security if he chooses.)

Jonathan Sallet, the lawyer for the states, then went into his argument. He focused on the viability of the Chrome spinoff, and points out that with 4 billion users, Chrome is quite valuable as a potential advertising platform and source of user traffic. Judge Mehta asks if in the spinoff, other search firms, essentially Microsoft, could buy the product. The answer is yes.

Sallet made another argument, this one on the ‘contingent structural relief’ of Android. Basically, if restrictions on Android don’t bring new players into the market, then Google will have to spin off that line of business. Judge Mehta asks about legal procedent, and Sallet says it’s not in Microsoft, but it’s in merger law, the so-called ‘crown jewels provision,’ which is, according to Google AI Overview, “a requirement in a settlement or consent decree for a company to divest more valuable assets if an initial divestiture package doesn't sell within a specified timeframe.” (Sallet is wrong, United Shoe is a monopolization case that didn’t come from mergers that nonetheless had a divestment.) Again lots more quoting back Judge Mehta’s opinion.

Google’s View

Then came Google’s lawyer John E. Schmidtlein, whose main argument hinged on something called a ‘but-for’ premise. Under this standard, the Antitrust Division had to prove at trial that Google used unfair tactics to maintain its monopoly power. In addition, it also had to show that “but for” the unlawful behavior Google’s monopoly would never have been achieved.

Specifically, at no one point did any distributor - Apple, Verizon, Samsung, et al - say that ‘but for’ Google’s exclusivity agreements they would have signed up with Bing. Google argues that since the DOJ didn’t prove the unlawful conduct protected the monopoly, and the judge didn’t say ‘but-for’ in his decision, a remedy seeking to terminate the monopoly itself is excessive.

Google also made the case that the standard to implement a remedy is fairly high, that there must be a “significant causal connection between conduct and maintenance of monopoly power.” The actual monopoly itself isn’t important, what matters is that the illegal behavior be stopped.

Google’s basic position seems to be that they do not really think they lost the liability phase, and that they will be vindicated on appeal. That’s not crazy, considering the possible composition of a D.C. Circuit Court panel, which tends to be stacked for big business. In terms of the standard for remedy, Schmidtlein argues that the DOJ remedy proceeds from an incorrect premise. The proposal is intended to “terminate monopoly power through radical government action,” emphasis on radical. It goes far beyond the orbit of antitrust law, designed to prop up rivals, harm competition and innovation, and injure privacy and national security. “Restoring competition sounds like a great phrase,” Schmidtlein said, but what exactly does that mean?

To be honest, I found Schmidtlein’s presentation risky, he sounded offended at the very premise that Google should have a remedy imposed for its conduct. Over and over, he would exhort that a certain remedy would force Google to have to compete with rivals who did not deserve access to Google’s property. At one point, he attacked the remedy on the grounds that “Google has a scale advantage they lawfully achieved.” It’s a bold strategy, to essentially wish away the judge’s liability finding. I did find an amusing line at one where, where Schmidtlein said that too much transparency in advertising data was a problem, because “advertisers can rig the auction” if they know too much. That is of course the linchpin of the Google adtech case the company just lost; Google itself was rigging auctions!

Schmidtlein’s a good lawyer, and I don’t fault him for his approach. I think Google leaders have decided they are totally unchastened by antitrust cases, and will not give an inch unless absolutely forced. Schmidtlein is doing his best to scare Judge Mehta into a narrow remedy, implying Mehta’s decision will be overturned on appeal. Google’s show is for the appeals court, and ultimately, the Supreme Court.

To this end, Schmidtlein points out that Google’s search quality is not a result of its bad behavior, which Mehta traces back 15 years. Google was great long before that; Google was recognized as a verb in 2006 in dictionaries. Google continue to innovate, which is something even Mehta recognized in his opinion. Judge Mehta chimed in with questions around the standard for structural versus behavioral remedies, giving Google another chance to call the DOJ’s remedy “extreme.” Schmidtlein reiterated the but-for argument, pointing out that no DOJ experts were asked to consider a but-for framework. More arguments were:

Mehta asked if break-ups are reserved for monopolies built via merger. Schmidtlein said historically that’s true, but doesn’t have to be.

Breaking off Chrome requires moving out lots of internal parts of Google that service Chrome, since there’s no specific Chrome line of business and the browser doesn’t stand alone as a business. What would a break-up even mean? The remedy proposal doesn’t say.

Google in the proposal can’t operate any browser for 10 years. Schmidtlein again harps on how extreme that is, says he can’t remember any remedy like that. Moreover, Google’s distribution on Chrome wasn’t really part of the case. And the DOJ’s expert, Tasneen Chipty, said divesting Chrome would at most move 4% of the market.

No buyer would be as innovative as Google, which built Chrome to begin with. Lots of browsers rely on Chromium, and they would be harmed. Expect to see withesses from Apple (Eddie Cue), Verizon, Samsung, Brave, et al.

Judge Mehta noted that one of the fruits of Google’s illegal search monopoly data was search data, and that a remedy should “at least try” to disgorge it. Schmidtlein did not deny that Google’s remedy failed to address ill-gotten data, and instead argued that the DOJ should have proven exactly what “quantum of data” was ill-gotten.

Schmidtlein found the forced disclosure of Google data and syndication, as well as ad bids, the most odious of the proposed remedies. It would allow tremendous insight into Google’s behavior by rivals, it’s a “wish list of competitors” to get trade secrets, it lets them “clone Google search,” as well as “reverse engineer Google’s trade secrets” that took decades to build, and a “hand-out” to rivals who don’t want to have to compete for distribution.

General artificial intelligence is a competitive marketplace, with a host of rivals, so there’s no reason to limit Google’s investment or products in the space.

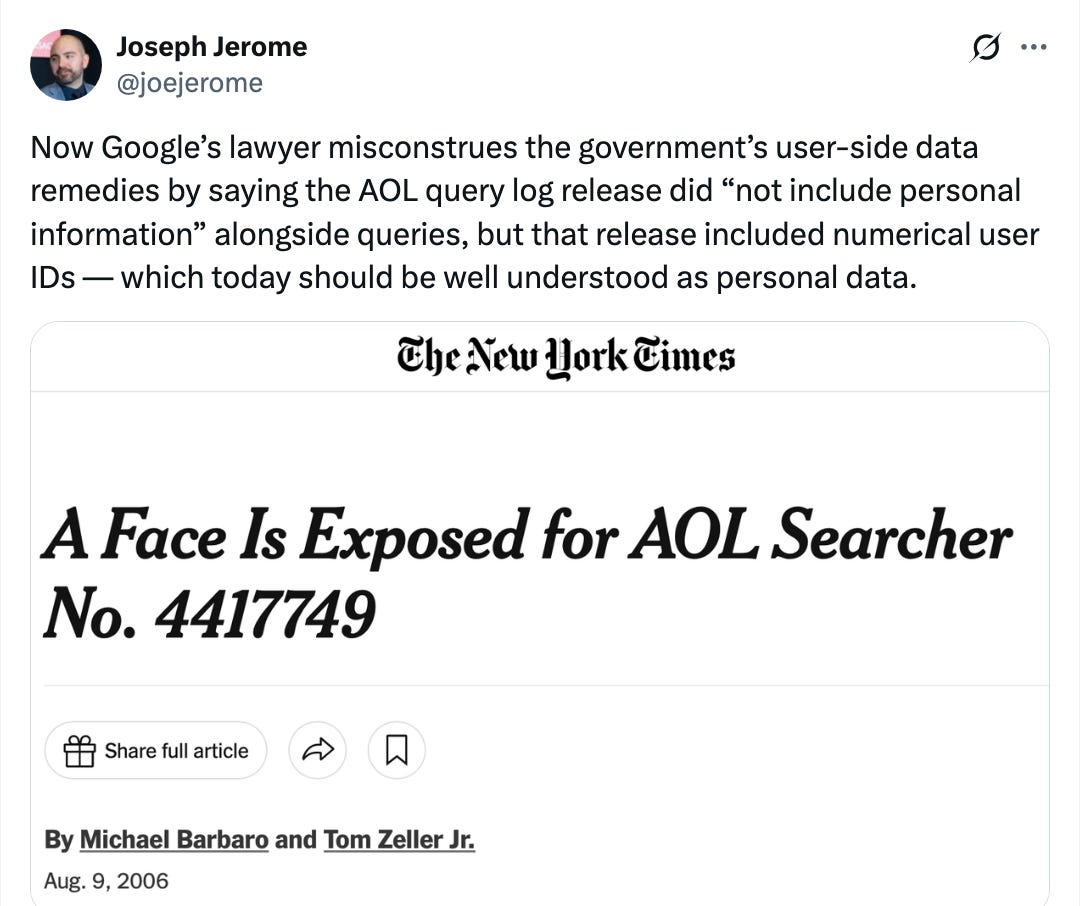

Forcing the sharing of data with rivals, even if anonymized, would risk sacrificing privacy and prevent Google from working with the U.S. government to protect national security. He pointed to an experiment in 2006, when AOL released a data log without personally identifying information, and researchers could in fact match the data to specific users. That said, there is a bit of bad faith going on here, as Joseph Jerome pointed out.

The Testimony Starts

There were two witnesses in the afternoon. The first was Gregory Durrett, a computer science professor from the University of Texas. Durrett is an expert for the DOJ, and he testified on generative artificial intelligence, walking the court through the importance of Google’s existing advantages in the space.

Google has three main generative AI products adjacent to search: (1) the “AI Overviews” widget embedded in Google search (2) the Gemini model, and (3) the Gemini app. Durrett’s main point is that generative artificial intelligence and search, when combined, are far more powerful than either one apart. Google's own public documents state that while LLMs are "brilliant at generating context, they need a way to anchor their responses" and "search is what anchors a model's output in reality."

A large language model, trained at a discrete point in time on a discrete set of data, is quite limited. It gets stale very quickly. If you allow it to access a real-time search engine like Google, however, using what is called “retrieval augmented generation (RAG),” then the tool becomes timely and far more accurate. Google’s search engine and infrastructure, by implication, gives Google a substantial leg up on competition. The syndication and data sharing remedies, he argued, cure that defect. Google spent some time fencing in Durrett’s opinion, making it clear he hadn’t compared Google’s advantages with the existing options in the market.

The second witness from the government was Peter Fitzgerald, the VP of Global Partnerships and Platforms for Google. He was hostile and unyielding, but testified that Google has agreements with partners like Samsung and Motorola for Gemini App distribution, under which Samsung and Motorola preinstall the Gemini App at certain “entry points” in return for a share of Google’s revenue. These agreements, according to the DOJ, were similar to the contracts Mehta declared as illegal during the liability phase. Tomorrow, the testimony with Fitzgerald will finish up.

As I said up top, Big Tech on Trial will be focused on the Meta case, but I wanted to lay out the main contours of the dispute over how and whether to break up Google. We’ll try to check back in with the Google search remedy fight when time allows.

Google is not better than everyone else in technology as they bragged for so many years.

They don't have the best Chatbot.

They couldn't make a 3d engine for videogames.

Their social attempts were pathetic.

It's phones are not leaders.

Google can win where it is first or can buy the leading company (i.e. Doubleclick, Youtube).

Otherwise Google is unremarkable.

Google says its so smart it deserves all the data it got by breaking the law.

No way. Sorry Google.

I hope Judge Mehta gives it to Google and their high priced lawyers.

Even if ultimately the ball-less, Trump-controlled Supreme Court throws it all out.