The Rage of Google

The DOJ put forward a proposal to take apart the search giant's market power. What happens when antitrust stops being polite, and starts getting real?

“Where we think it really harms our ability to innovate on behalf of our users, we are going to be vigorous in defending ourselves.” - Google CEO Sundar Pichai

What happens when antitrust becomes a reality for a company’s executives? For eight years or so, Google has been in the cross-hairs of public opinion, with lots of chatter about their monopoly. But it’s all been theoretical, just some Congressional hearings with grandstanding politicians, mean stories in the jealous New York Times, complaints from rivals and customers, tweets from Trump, etc. Google leaders and stakeholders could waive that stuff away, pretend they wouldn’t face consequences, that they could just set lawyers on the problem, and float above it all.

And that wasn’t a crazy view. In fact, it would have been weird if they didn’t think that. No large tech firm has even faced a monopolization challenge since the 1990s, let alone lost one. So in the mid-2010s, when the chatter and investigation started, well, any consequences would be a long way off. In 2020, when the first antitrust cases were filed, it wouldn’t seem to matter either. The precedent was on the side of Google, and even if it wasn’t, it would be years before anyone at Google would have to face the music.

But the time of theoretical consequences is over. In August, Judge Amit Mehta ruled that Google is a monopolist that has violated antitrust law to maintain its dominance in search and search ad. "After having carefully considered and weighed the witness testimony and evidence,” wrote Mehta in his decision of the case United States of America vs Google LLC, “the court reaches the following conclusion: Google is a monopolist, and it has acted as one to maintain its monopoly. It has violated Section 2 of the Sherman Act." And that’s the second case the search giant lost, the first being a private monopolization suit by Epic Games over its control of the Android operating system and app store which was ruled on in December of 2023.

Even so, while Google has violated the law, there are as of yet no remedies, and still, few consequences. The company is no longer able to engage in significant mergers due to regulatory risk, its business and profits seem unaffected. But this week, that may have changed. First, the judge presiding over its Epic Games case ordered Google to allow rival app stores on Android, and barred forms of preloading, revenue sharing, or most other tricks it used to maintain exclusive control over Android phones. And second, on the search case, the government put forward its high level remedy proposals.

The DOJ suggested a moderate set of methods to eliminate Google’s monopoly power. It did not go that far; there are no requests for Google to divest its huge store of ad inventory - YouTube - or its remarkable self-driving car division, Waymo, or even its extensive data infrastructure. It did not even really ask for a break-up, though there are hints that such a proposal is something the court should consider. Yet, it’s clear they mean business, and Google knows it.

All remedies are tethered to the legal violations, and so that’s where we have to start in understanding what the government wants. Judge Mehta decided that Google broke the law by using contracts and revenue sharing with Apple, Verizon, Mozilla, and so forth to shield itself from rivals in search, preventing distribution of competitive products. Through this scheme, went the judge’s argument, Google built scale and data stores that entrenched its market position.

There are two paths for a remedy. Should Mehta stop only the tactics Google used to build its monopoly? Or should Mehta address the underlying monopolization itself, the fruits of the bad conduct? I think Google expected they’d get to keep most of the business intact, but the government said that a lot of their market position must be taken apart.

“The remedies,” wrote the DOJ, “should account for alternative and future forms of monopoly maintenance in the affected markets and reasonably related markets in addition to the specific conduct to date.” In other words, Google’s acquisition of data and market positioning in search has led to significant power in other markets, and the court should make sure that it cannot have a competitive advantage due to its earlier unlawful behavior.

It proposed four broad changes. First, Google can’t keep its distribution deals with Apple, et al, including “default agreements, preinstallation agreements, and other revenue-sharing arrangements related to search and search-related products.” There’s some wiggle room for much smaller entities, but the big deals are over. It also might have to spinoff Chrome, Play, and Android, or have significant restrictions on them, because, as Mehta put it, Google’s control “significantly narrows the available channels of distribution and thus disincentivizes the emergence of new competition.”

Second, Google has to share data or license data it got from its illicit behavior, including “indexes, data, feeds, and models used for Google search, including those used in AI-assisted search features,” as well as search results, features, ads, and ranking signals. Cleverly, while privacy concerns are real, to prevent Google from using privacy as a pretext to shield data, they seek to “prohibit Google from using or retaining data that cannot be effectively shared with others on the basis of privacy concerns.”

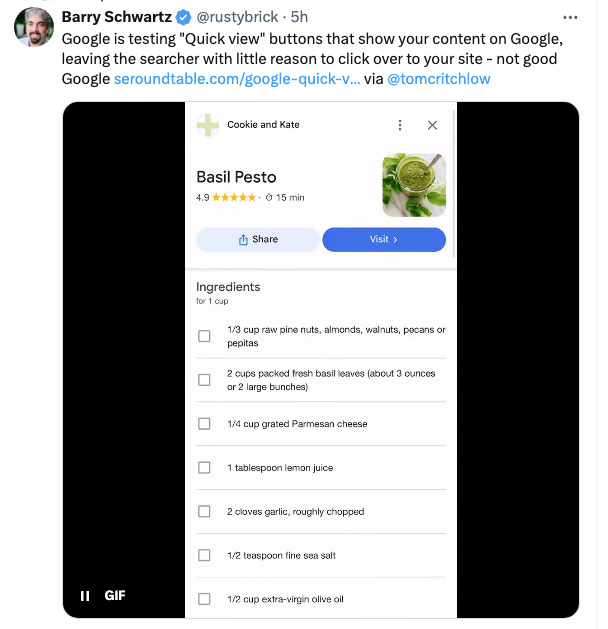

Third, the DOJ wants to make sure that Google doesn’t leverage its market power in search to get market power in AI-powered search, or generative AI plus what’s known as “retrieval-augmented-generation-based tools.” To that end, remedies would include allowing publishers to opt out of having their content used for Google’s AI training and display purposes. For instance, the following kind of behavior is now routine, because Google tells publishers if they want to appear on its search results they must concede to being part of some of its AI training. That kind of coercion would be over.

Finally, the DOJ is seeking to address a different source of Google’s power, which is its scale and control of advertising demand. Hundreds of thousands of companies, if not millions, use Google search ads, and that accumulation of ad buying power gives Google considerable discretion on where to direct revenue. Remedies here might include licensing of Google’s ad feed “independent of its search results,” and more power for advertisers over the placement of their ads. Basically, Google has an ecosystem it taxes, and the government is seeking to find ways to pry open that ecosystem so rivals can start to compete.

There are also some procedural elements, like document retention and training mandates, and an anti-retaliation provision. Google has been destroying documents it was legally required to hold, so these make sense.

What’s striking about most of these remedies is that, with the exception of divestments, most of them have broad consensus. At this point, even pro-Google voices are saying “well sure regulation and sharing of data is fine and get rid of the contract with Apple.” Ultimately, though, this consensus is moot, since the remedy is less about the specific bad conduct and more about forcing a monopolist to stop engaging in coercive behavior. And there’s bitter resistance to that idea, because most of today’s winners in the economy won using coercion.

So again, what happens when an antitrust case becomes real? Well, in Google’s case, their leadership seems quite angry at being told they have any legal limits whatsoever. In a remarkable blog post that no doubt went through levels of edits from many lawyers, the company responded to the proposal by alleging that government enforcers are “radical,” a threat to “privacy and security,” that they will break your phone and browser, destroy the free press, hurt business at large, undermine investment, and destroy America by “hobbling” U.S. “technological leadership.”

That’s not all, of course. Google has a savvy PR operation, and they have been sending surrogates and friendly politicians all over the business press to attack antitrust enforcers. Aligned oped boards, like the Financial Times and The Economist, are aggressively bashing the government. CNBC, when not covering the hurricane or elections, had a nonstop commentary over Google and antitrust. For instance, here’s ex-Googler Bret Taylor on CNBC, talking about cluelessness of our elected leaders.

Politically, Mark Cuban, a Google consultant who says he speaks with the Harris campaign every day, said he’d fire Lina Khan if he were President, and, though she’s not the one bringing the case against Google, it’s largely due to the broad administration push to address monopolization by big tech. And that’s not even bothering with the whole surfeit of Google-financed trade associations and academics quoted in the press.

Their most powerful argument is that we need large firms to build technological supremacy, with the observation that a scientist whose company was bought by Google just won the Nobel Prize. The counterpoint seems stronger; most major technological innovations - from the creation of key forms of gasoline cracking to the transistor to the personal computer to Google itself - happened because enforcers pushed incumbents out of the way through antitrust suits.

But this isn’t about logic, it’s about worldview. One way to understand the differing perspectives is as follows. Google has been engaged in coercive behavior for years, and used the loot from that bad behavior to erect huge fortifications against rivals. The DOJ doesn’t think it makes sense to say, well you’re no longer allowed to rob people in the same specific way you did before. Because if that’s the fix, then Google will just find new ways to engage in coercive behavior. To fully fix the problem, you have to take away the fortifications and the ill-gotten loot, as well as place significant restrictions on conduct. From Google’s perspective, this framework is insane; most of its gains are a result of effective product design, not coercion, so nibbling around the edges is the only legitimate mechanism for a remedy for a case that shouldn’t have been brought anyone.

Over the next six months, this question is what we’re going to hear debated in court. Procedurally, now that the DOJ offered its broad remedy recommendations, there will be discovery, which means we’re going to see more documents from inside Google. There will be witnesses and a sort of mini-trial. The DOJ will put forward a more specific set of recommendations. Google will suggest how it sees appropriate remedies. And the judge is going to issue an opinion by next August.

But that’s not all. There is also the decision hanging over Google in the third antitrust trial, over advertising software. And that means Google might be facing yet another liability finding for monopolization. All three cases - over app stores, search, and adtech - intersect insofar as Google’s monopolies fortify one another. The judges will likely work together to manage remedies. There will of course be appeals, and a hope that the higher courts will overturn these decisions.

I suspect Google’s main play, however, is political. Advisors to Kamala Harris, such as Karen Dunn and Mark Cuban, are affiliated with Google, and while we don’t know what Trump will do, many Republicans in the Senate who must confirm Trump nominees are in thrall to big tech. And that means Google will seek to win through lobbying what they lost in court. Their goal is to appeal these cases, and have a higher court delay any sort of remedy while the appeal is heard. In the meantime, they will seek to have Jonathan Kanter fired and get a new head cop in place who is more friendly to their point of view. If they can engineer such an outcome, the thinking goes, then they can escape liability.

Will that scheme work? Perhaps, but there are reasons it might be more difficult to pull off than they assume. If Google gets control over the Antitrust Division, a lot of members of Congress will be furious, as well as a significant slice of the media, and the base of both parties. In terms of the cases themselves, state attorneys general are co-plaintiffs, so they will have to agree to drop the suit or to modify terms. Most importantly, the judges themselves will be frustrated if the plaintiff terms suddenly change for political reasons, since they have been working through evidence for years.

Ultimately, there are two things that cannot be reversed. One, monopolization law itself is back. No longer are dominant firms insulated from private suits or Federal suits. And two, Google is now an illegal monopolist, and it can never escape that label. There are plenty of reasons that Google will say it’s doing wonderful things, and in some cases it is, but it is no longer the plucky company that once said “don’t do evil.” And everyone knows it.

It's funny that you mention big tech being cool with Trump. Remember, it all happened when the dems over blown Jan 6 and the Russia gate bullshit. Twitter kicked him off even though he said nothing at all that they pretended he said.

I'm not a Trump supporter but I can't help but notice your bias and blindness. Big tech is pro authoritarian, pro censorship whether it's the RepubliBLOODS or DemoCRIPS.

The real solution is not blue or red. It's populist instead.

How much has Google’s ad monopoly destroyed the news business? Didn’t all the media companies give up on print ads because Google’s digital ad biz was the future, but digital ads didn’t bring in enough profit for news companies to survive (thanks, Google!), and our media quality has been so degraded since then.