Google Loses the Adtech Monopolization Case

Judge Leonie Brinkema ruled against the search giant for its control over the software underpinning online ad buying. Now it's on to the remedy.

"The essence of antitrust law is to try to keep the system working by recognizing that, at certain points, some companies may get too big for their own good, they're self-imploding, or the technology may become so dominant that it's just crushing all other elements where there can be innovation." - Judge Leonie Brinkema, 2023, United States v. Google LLC

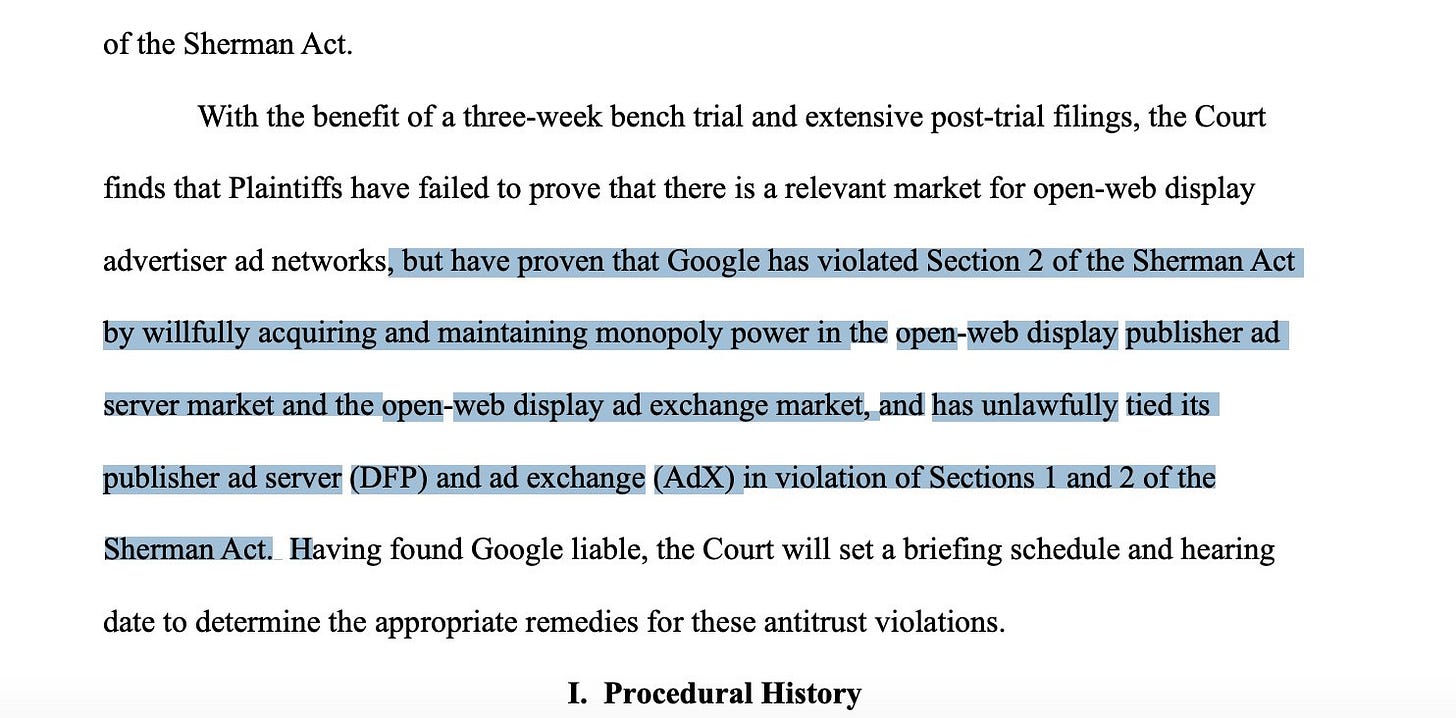

Today, Judge Loenie Brinkema, in a detailed opinion, ruled that Google is an unlawful monopolist that controls the software used by publishers to manage online ads as well as the exchanges used to buy and sell them.

This case, brought by Biden enforcers Jonathan Kanter and Doha Mekki, is a big deal. The decision also dropped the same week that the Meta antitrust trial started, and the week before a Google remedy phase in an earlier antitrust trial begins. As former FTC enforcer Jonathan Newman put it:

This particular case, interestingly, is not about Google’s power over search. I described it in a piece in September titled “A Post-Google World;” the gist is that every newspaper or website that wants to sell ads pretty much has to use Google’s software to place and match ad buyers and sellers. And the reason is Google has bought a bunch of companies and engaged in practices like tying its products together and excluding rivals from the market by restricting whether its customers can use non-Google services. As a result, Google’s middleman software services take between 30-50% of revenue spent by advertisers on ads meant for publications, instead of 1-2%. So if the judge finds a good remedy, it could mean billions of dollars more for the press, because Google won’t be able to take nearly as much.

I want to make a few key points about her decision.

First, this decision is now the third loss for Google. In 2023, Google lost a monopolization case to Epic Games over its control of the Android app store. Last year, the company lost a case over its control of search. And today, it lost a third case over yet another line of business. These decisions build on each other, Brinkema cited the decision in the search case to describe why Google had control over so many small advertisers. Referencing across the cases will continue to happen, as we move into the remedy phase. Additionally, private and state antitrust cases, like a case led by the Texas attorney general on adtech currently working its way through the courts, will benefit from this decision.

Second, this decision shows antitrust cases just don’t have to take as long as they do. The complaint for this one was filed in January of 2023, and it has been decided just 26 months later. Contrast that with the Facebook antitrust case, which was filed in 2019 but is only now going to trial, six years later. Or take the Google search case, which was filed in 2020 and was decided four years later. That’s hundreds of billions of illicit gains happening in the shadow of litigation. Yes, antitrust suits are complex, but they are also inherently imprecise.

Cutting two thirds of the work and time is a huge improvement, and Congress and judges should seek to make that happen by requiring courts to adopt procedural rules like those used in the “rocket docket” federal court in Virginia where the Google adtech case was litigated. I would note that Congress already started this in 2022, passing a law that allowed states to choose the venue of their antitrust cases. Judge Brinkema cited this law when denying a transfer request from Google to move it to the Southern District of New York, which would have delayed the case indefinitely. Procedure matters! Also a non-ironic yay Congress!

Third, this decision is highly damaging to the profession of big law. Kamala Harris advisor and Democratic leaning big law firm Paul Weiss partner Karen Dunn oversaw the case for Google at the same time as she was advising Harris’ campaign. It’s a pretty brutal career moment, made even worse by Paul Weiss’ recent decision to cut a deal with the Trump administration. (Dave Dayen and I did an important Organized Money episode with Paul Weiss alum Jonathan Kanter on how these firms make money and why the current moment is so destructive.)

More specifically, all three judges overseeing these Google cases have ruled that the company’s lawyers acted unethically, specifically calling out its top lawyer, Kent Walker for false claims of privilege and for allowing the wholesale destruction of documents while on a litigation hold. Here’s Brinkema today:

Google employees and executives also misused the attorney-client privilege. For example, Kent Walker, an attorney who served as Google’s President of Global Affairs and oversaw the company’s legal team, marked an email in which he asked his colleagues for reactions to a New York Times article as “privileged…”

Google’s systemic disregard of the evidentiary rules regarding spoliation of evidence and its misuse of the attorney-client privilege may well be sanctionable. But because the Court has found Google liable under Sections 1 and 2 of the Sherman Act based on trial testimony and admitted evidence, including those Google documents that were preserved, it need not adopt an adverse inference or otherwise sanction Google for spoilation at this juncture. As in Google Search, the Court’s decision not to sanction “should not be understood as condoning Google’s failure to preserve chat evidence.”

Four, this decision is an illustration of how judges are updating antitrust law as they confront modern commercial realities. When judges write decisions like this, they interpret the laws and set future precedents.

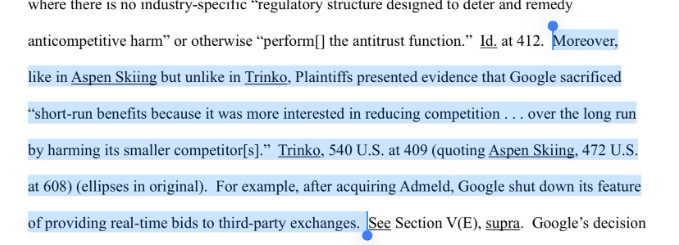

There’s a 2004 decision I’ve written about in the past, called Verizon Communications Inc. v. Law Offices of Curtis V. Trinko, which made it much harder to bring monopolization cases. In that decision, the Supreme Court unanimously said that monopolists like Verizon were allowed to deny rivals access to their networks. This decision allowed big tech to emerge, because it scared enforcers away from arguing that network systems like software platforms or social media could engage in unlawful monopolization.

Starting a few years ago, due to the Biden antitrust division’s savvy use of amicus briefs, judges began chipping away at the Trinko precedent. And this decision continues that process. Brinkema says that in this case, Trinko doesn’t apply for three reasons. She noted that Google wasn’t blocking rivals, but customers. She also said that Trinko was more relevant in regulated markets like telecom, not unregulated markets like advertising. And she pointed out investment patterns of a monopolist - a willingness to sacrifice short-run benefits to harm smaller competitors for longer term benefits - could mean Trinko doesn’t apply.

We will see more private monopolization cases as a result of this legal challenge.

And my last point is that the likelihood Google is taken apart has gone up. The judges involved in the various Google decisions are likely going to have to coordinate with one another over how to manage the various remedies, and at some point, consent decrees over behavioral elements are simply too complex to administer, especially when the legal authorities within the company are engaged in bad faith. They may need to allow technical committees managing such decrees to share information; especially important since we know Google will look to exploit any loophole and engage in malicious compliance.

Politically, it is of course possible Trump tries to settle this case on his own. Though the case was spearheaded by the DOJ, there are other plaintiffs, notably state attorneys general. So the DOJ can pull out and settle, but states don’t have to. (That’s not the case for the Meta fight, since the judge dismissed the states as plaintiffs for annoying technical reasons.)

Anyway, I’m writing this from the Meta courtroom, where I’ve spent the past few days listening to Mark Zuckerberg and Sheryl Sandberg under cross-examination by government lawyers. It’s a tough case, though it’s going well for the government. Zuckerberg is a clear writer, and he put everything he was trying to do in writing at the time he was doing it. That doesn’t mean it’s a slam dunk. The judge has been somewhat skeptical, and there are some disturbing reports that Trump is open to settlement, along the lines of a large fine and a consent decree, which is a very European approach that doesn’t deliver real changes in the marketplace.

But the broader dynamic here, as illustrated by the Google decision, is unmistakable. The antitrust revolution rolls on. And I’m as surprised as anyone else about that.