Day Four: Simple. Uniform. Flexible. Google's Ad Tech Code Makes the Case for a Break-Up.

A computer science professor makes the case for a break-up, and the empire strikes back. Judge Brinkema may have seen enough.

The main event. We’ve known that the key to crafting a divestiture remedy in this case is the technological feasibility of that divestiture. Earlier in the week, Judge Brinkema expressed frustration with industry experts, whose opinions weren’t really relevant to the core issue of tech feasibility. Today, we got a lot more clarity, including from the Google Exec who would know better than anyone else. And, just four days into the remedies hearings, Judge Brinkema tipped her hand that she may have seen enough.

Much of Day 4 consisted of continued testimony from Professor Jon Weissman, the Justice Department’s computer science expert witness, who started his testimony late yesterday. Judge Brinkema has made it clear that she considers the testimony of the computer engineers—from both sides—to be the most important part of the trial. Weissman must have been music to her ears.

Weissman walked the court through the technical processes that would be required to implement the DOJ’s various remedy proposals. He covered a lot of ground and did it slowly and thoroughly. His main focus was the DOJ’s divestiture proposals: divest Google of its advertising exchange (AdX); make the Final Auction Logic portion of Google’s publisher ad server (DFP) open-source; and divest Google of the remainder of DFP, if necessary. The main question he was asked to investigate is whether these divestitures are technically feasible. It won’t spoil the ending if I tell you he concludes they are indeed feasible; he is, after all, DOJ’s witness.

Weissman’s expertise is in distributed systems and cloud computing. AdX and DFP are both distributed systems, meaning they run on multiple computer systems. The question of feasibility is primarily a question of migrating systems. We got an introduction to this topic two days ago from James Avery of Kevel, but that was more the business perspective on it. Weissman got us into the nitty gritty. He broke the migration process down into three steps: identify, separate, migrate.

At the first step, we identify the relevant source code, its dependencies, and the potential replacements for those dependencies. “Dependencies” are the parts of the code dependent on remaining in their current environment, so they are the parts that will have to be replaced to recreate the system in a new environment. At the second step (separate), we copy the relevant code, and write “adapters” for the replacements for the dependencies. At the third step (migrate), we move the copy of the code to its new environment, replace the dependencies (the parts that couldn’t come along) with substitutes, and test the new system in its new home. All very methodical.

“Technically feasible” means that the migration process will not require any major system redesign and relatively little from-scratch code rewriting. This latter is the main point of contention: Google insists that migrating AdX or DFP will require enormous amounts of from-scratch rewriting of code. It claims that so much of their proprietary code is so intimately entwined throughout their systems that it is pretty much all dependencies, all inseparable parts. This is Google’s challenge to Weissman. Judge Brinkema’s challenge to him was that the future homes of AdX and DFP are unknown, so how can he know they will work in the as-yet-undetermined new environment? He has a similar answer for both.

Weissman’s method for checking technical feasibility was to go read the source code at Google. (He couldn’t take it off-site. Come on, it’s proprietary.) But what was he looking for? He said Google’s code was “beautiful.” That assessment is more than flattery; it’s actually relevant. He walked us through—of all things—a style manual for training Google engineers. The manual teaches engineers to write “modular” code so they can “easily update technical infrastructure” because components of the system will constantly change. It articulated five principles of good code: simplicity, uniformity, flexibility, separation of concerns (i.e. a single function in a module), and test-ability. What Weissman was looking for was whether Google’s engineers actually implemented their training. And what he found was beautiful code that followed these beautiful principles and created systems that would be beautifully easy to migrate.

Common sense reinforces Weissman’s method. He checked the “hot spots” in the system along with a healthy sampling of other spots. (I used to work in a grocery store, and when you get a hundred flats of strawberries, you check five or six random ones to see the quality.) People migrate systems all the time, and although Google is bigger, what matters is how much has to be changed or replaced (the dependencies), not how big the system is. The world is full of people in the business of providing similar functions; clouds want clients and provide services to attract them. Replacement software needs to be functionally equivalent, not identical, to what it replaces, so it will use the sub-routines that come with it and doesn’t have to work with its predecessors. And so on. Pragmatic ideas like these informed Weissman’s assessment of technical feasibility.

On cross-examination, Google leveraged its immense scale to undermine Weissman’s practical analysis. Instead, he had to repeatedly acknowledge he had not read every line of code, identified every dependency and its replacement, fully carried out all three steps of an AdX or DFP migration, or planned for every complication that an as-yet-unknown future environment might present. Still, his earlier testimony had prepared us to recognize that those things are not how technical feasibility is identified. It is identified by source code written well in modern, widely-used languages according to effective style guides in modular form by capable engineers who produce simple, uniform, flexible, single-function, testable products. Weissman made a good case for the DOJ.

Following Weissman’s testimony, we heard testimony from Tim Craycroft, Vice President and General Manager of Google Advertising. Craycroft was listed as a witness by both the DOJ and Google. He’s a senior manager with some 2,700 employees under him, most of whom are engineers. If anyone inside Google knows about the feasibility of a divestiture, it’s this guy. And right away, we learned from Craycroft that Google had studied essentially the same divestiture feasibility they have been so strenuously denying in this trial.

Google conducted divestiture feasibility studies many times over the past five years, long before the current case was filed. In 2020, “Project Sunday” examined separating AdX from DFP. In 2021, “Project Monday” looked at divesting AdX and making part of DFP open-source. A third project, in 2023-24, looked at selling AdX, open-sourcing the DFP auction logic, and having DFP bid into Prebid - practically the whole DOJ structural remedy. Apparently, this all looked feasible to Google on the inside, though Craycroft insisted it was not a real divestiture they were looking at, but only a “business transfer” that included only “illustrative” “reference code,” not real source code, and therefore proved nothing about the technical feasibility of real divestiture.

Despite the ostensible feasibility of a divestiture - even according to Google’s own internal analysis - Craycroft seemed combative, denying that pretty much any part of the DOJ’s remedy plan was feasible, and insisting that migrating AdX or DFP would require fully recreating their source code, more or less from scratch. Still, it was clear that Google had considered various related scenarios.

Craycroft’s testimony also provoked one of two revealing interjections from Judge Brinkema. In the course of arguing that preparing to sell AdX would take years of work, Craycroft testified that it would be more straightforward to just shut down AdX. We heard this idea from Jay Friedman on Day Two, that AdX outside of Google is just another ad exchange we don’t need. (And maybe it’s such a big one as to be a problem for the market, whoever owns it.) Craycroft’s threat that Google might just shut down AdX altogether prompted Judge Brinkema’s interruption:

“If the decision were to just wipe out AdX, wouldn’t publishers get the same demand bids from Prebid? Couldn’t that be an elegant solution?”

The mealy-mouthed response amounted to a “Yes,” although Craycroft couldn’t say so directly. But the reality is that Google has tools, including something called “gBid,” that would allow its publisher ad server to bypass AdX altogether and go straight to the advertiser network. Not only might a divestiture be feasible and necessary, it might not be enough to wrest online display advertising from Google’s grip.

On re-direct, where DOJ gets to respond to Google’s cross examination of Craycroft, DOJ asked Craycroft another strategic question: Would Google be prepared to lower its monopoly 20% take rate on its ad exchange? The answer: No. Google is not prepared to face the consequences of its monopoly.

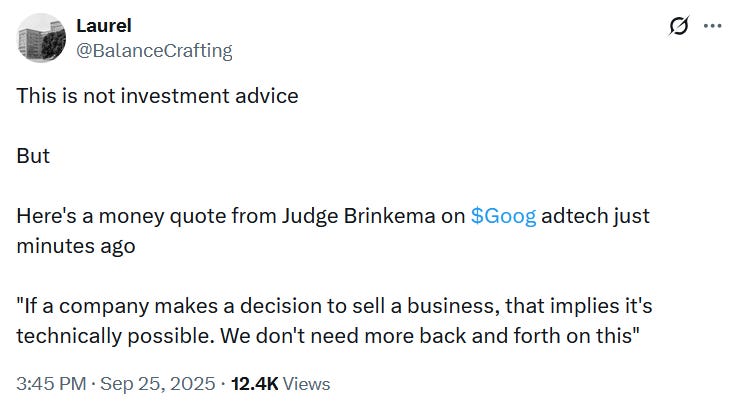

In sum, Google Ad Tech Day 4 gave us key testimony on perhaps the key determining variable in whether Google will be broken up: technical feasibility. And anyone looking for how Judge Brinkema, with all her trademark wit and directness, might be thinking about the question, here’s how Laurel Kilgour of the American Economic Liberties Project summarized it:

That might be an auspicious statement for those seeking relief in the form of a break-up. But it’s not all bad for Google. To some extent, they’ve considered whether a break-up might be best for Google too.

The excitement is building!

Get edited. A rudimentary word-processor (Gmail) flagged this error in your first paragraph: "...And, just four days into the remedies hearings, Judge Brinkema tipped her hat that the "SHE"may have seen enough.'