Day 8: Does Google Deserve a Good Price for its Monopolistic Weapons?

An investment banker, an economist, and a small business owner who all earn money from Google walk into a courtroom...

Let’s talk about capitalism. Day eight was economics day at the Google ad tech remedy trial. An investment banker, an economist, and a small business owner testified in Google’s defense. I will give you some details, but you can probably guess the general vibe. The real action was in the vision of capitalism Google is presenting as Assumption A.

Shane Goodwin

“Uncertainty” was the theme of Shane Goodwin’s testimony. Goodwin is a professor of finance at Southern Methodist University, and an expert in mergers and acquisitions and corporate governance and strategy. He reviewed DOJ’s remedy proposals and finds them full of uncertainty. His report concludes that the proposals are speculative and risky: a) they are missing important details; b) large divestitures are risky; c) DOJ’s specific requirements raise risks; and d) they could deter buyers (of AdX and DFP). He breaks the uncertainties down: employee uncertainties—compelled to switch to new owners?; loyalty to Google?; attrition problems?—and customer uncertainties—contracts assignable?; loyalty to Google?; multiple buyers of DFP? “Customers are the lifeblood of an organization.”

Goodwin went on to list all the reasons buyers would be deterred, reluctant, or unable. I could recount them (missing details, divestiture complexities, historical failures), but you get the idea. Judge Brinkema got the idea, too, and about the time I was writing “Wouldn’t a buyer price in all of this?” she broke in to say that there would be a third-party monitor, if the divestiture is court ordered, and so wouldn’t due diligence on all these uncertainties be part of proper oversight? DOJ attorney David Geiger did well in cross-examination, arguing that all these challenges are met regularly in completed deals. He pointed to several witnesses we’ve already heard from who were willing to buy AdX and not confused about what is being divested. He asked if the court couldn’t order the scope of assets to be negotiated among Google, the buyer, and the court monitor. This elicited the best reply Goodwin gave all day: “I assume the court can do whatever it wants,” to which Judge Brinkema responded, “Good answer!”

That little exchange got a big laugh, but there is a serious conflict between his answer here and the whole spirit of his testimony. Goodwin assumed the goal was “a successful divestiture.” And by that phrase (used repeatedly), he meant what an investment banker would mean: to be successful, the divestiture would need to maintain the asset’s value; Google would need to get a good price, and the buyer would need to receive an asset that was not devalued by employee attrition, lost institutional knowledge, disrupted systems, etc., etc. But none of these strenuous efforts to ensure a “successful divestiture” have anything to do with what the court actually wants from the divestiture: to break up Google’s monopoly and restore competition to the markets.

The court can do whatever it wants. This is true, and important. The court can make Google sell AdX for a dollar. It doesn’t need to get market price. Or the court can simply dissolve AdX. (Remember Jay Friedman of Goodway Group testified on day two that he thought AdX should just be eliminated.) Or break it up and sell it in pieces. Maybe investment bankers would see these actions as causing catastrophic asset devaluation. And an affront to dealmaking—and dealmakers—everywhere. That’s a false capitalism, the bankers’-eye view. It ignores that whatever the optimal current “market price” for AdX may be, that value is, in part, the fruit of over a decade of illegal conduct. A true view of capitalism sees also the enormous windfalls on the other side of the ledger—the side where competition was suppressed. Someone gets AdX for a dollar. Or a bunch of companies get a bunch of new customers. Someone’s getting hardware at fire sale prices. Capitalism is an ecosystem with something like a conservation of matter principle: everything goes somewhere, and one person’s loss is another’s gain. Capitalism includes the people trolling bankruptcy courts and tax sales as well as investors and developers. Ironically, the tech world, with its ethos of creative destruction, is in tune with this resilient and holistic capitalism, yet it’s the investment bankers Google calls on to protect its precious creations. (Its precious, but illegally and anti-competitively used, creations.)

Andres Lerner

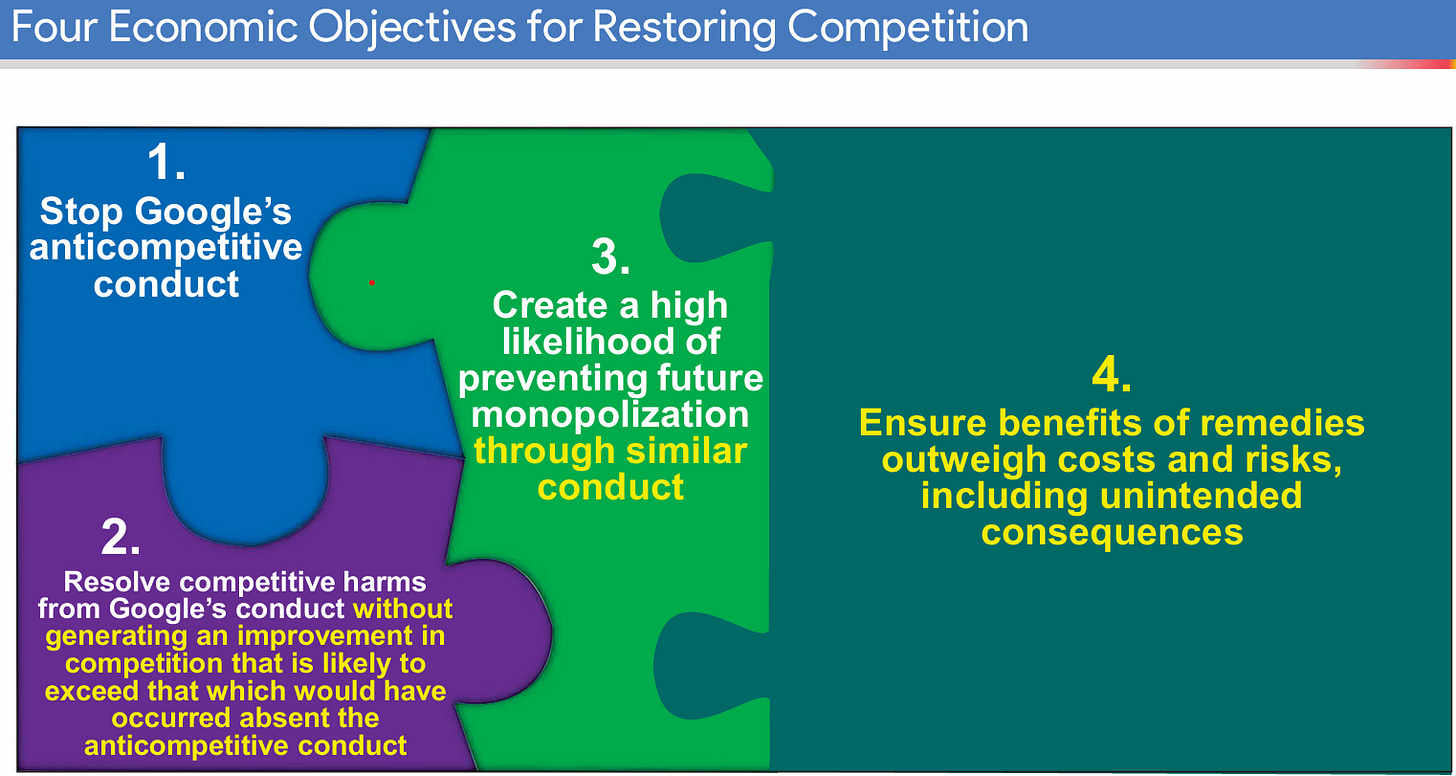

“Efficiency” was the theme of antitrust economist Andres Lerner’s testimony. Lerner’s mandate was specifically to rebut the testimony for DOJ of Robin Lee. He did this in a very specific way: by constraining Lee’s objectives and DOJ’s proposals with the requirement that they not correct any more harm than the exact quantum provably caused by Google’s illegal actions. Instead of deferring to the victor on remedies and resolving doubts against the wrongdoer, requiring this level of proof would flip the burdens around. Perhaps Goodwin’s arbitrary insistence that protecting asset value must be the court’s first concern put me on guard for these invented requirements, but the oddness of these constraints on how the court should think about remedies jumped out, and not just at me. When Lerner adjusted Lee’s objectives to constrain Google only from “similar conduct” to that which caused the monopolization, Judge Brinkema interrupted to ask if it was the conduct or the effects that would be banned. She said many in this trial are concerned about Google finding new strategies to accomplish the same effects. His answer here was vague, but on cross-examination later by Julia Wood, it was clear that he meant remedies should only forbid Google from repeating its illegal behavior; if it found a new illegal way to monopolize, that should be charged in a new trial, not anticipated in this one.

Much of Lerner’s analysis was based on a concept of the But-For World: the world that would have existed but for the illegal actions. He argued that the court’s goal in remedies should be to return the world to that state. One can imagine a justification for this idea as a hypothetical, a thought experiment to get perspective. But even lenient Judge Mehta from the Google search trial acknowledged that this is both an unrealistic exercise and contrary to legal precedent. Especially in a case where the wrongdoer destroyed or hid evidence of its wrongdoing, it doesn’t make sense to expect the victor to be able to quantify that But-For-World with certainty. Worse, Lerner said we should define the But-For World based on the trial opinion, meaning the But-For World would differ from reality only in ways that had been proven illegal in court. An action, though, has many ramifications beyond what could be proven in court! All the effects that are enabled or hidden or facilitated by wrongdoing would be considered part of the But-For World and would not be reversed or compensated. We may know the many “fruits” of illegal conduct, but only those few formally proved in court may be legitimately seized under this But-For standard. That’s Lerner’s argument here, and this shielding of Google’s ill-gotten gains seems to be its purpose.

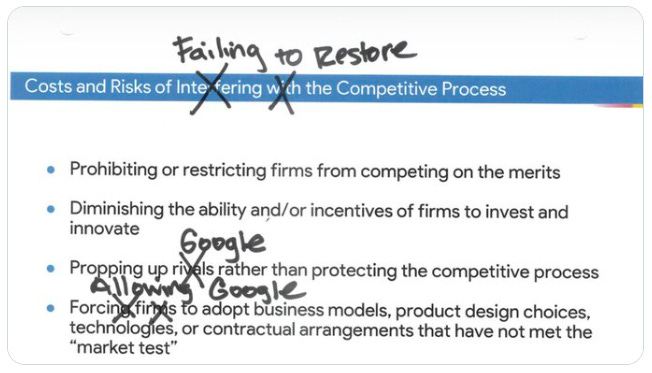

In cross-examination, Wood effectively showed the bias or asymmetry of Lerner’s analysis. Claims that DOJ’s remedies would undermine efficiency were pervasive in his testimony: eliminating the efficiencies of the monopolist would drive up prices and fees, undermine ad targeting, and create security weaknesses; DOJ proposals “will break these efficiencies.” But Lerner’s arguments always go one way, as if the efficiency is already there so any action will cause damage. But the liability trial proved that Google has already damaged these markets. Wood showed the bias by changing a few words on a Lerner list of “Costs and risks of interfering with the competitive process.” Under this heading were several ways such interference favors Google’s rivals. Wood changed “interfering with” the competitive process to “failure to restore” the competitive process; suddenly, the costs and risks on the list now all favored the monopolist. It showed how Lerner’s specious efficiency claims simply assumed away the very problems with ad tech markets that the court in this trial is supposed to remedy.

Elizabeth Douglas, wikiHow

“Worry” was the theme of Elizabeth Douglas’s testimony. She is the CEO of wikiHow, a website that posts instructional videos on how to do everything (450,000 of them). Her website is supported largely by advertising (about 80 percent), and it is having trouble. The trouble is mostly caused by the new AI summaries on search engines, which give people answers (such as how to do things) on the search result page. Having gotten their answer, people don’t go to webpages, so no ads get seen or paid for. This is not a problem that is fixable by any of the remedy proposals in this trial— and ironically, is inflicted by the very party she’s testifying for. Nevertheless, Douglas uses Google Ad Manager (GAM) and loves it, and she’s worried that DOJ is going to make GAM go away.

Douglas was Google’s most effective witness of the day, but purely for emotional reasons. “I’m here today because I’m worried for my business.” Her testimony was a moving and engaging infomercial for GAM. She uses it a lot, and partners with a bunch of other exchanges. She has used other ad servers, and found them less easy, convenient, or pleasant. She gets good service from Google. She’s worried about latency, support, and price, if Google is forced to divest GAM. Judge Brinkema asked what if AdX was sold to another SSP she already uses. “It’s the unknowns that bring me here today.” If she had to go to another ad server, it would be another setup: “We’d have to put work into it.”

She also has a “bigger, existential concern”: if Google is taken out of the market, the internet left behind with some good actors and some bad actors, and without Google’s “shepherding,” “the internet could fall away.”

But as Judge Brinkema no doubt picked up, Douglas is not just a customer who likes Google, but is a customer who is dependent on staying in its good graces. Douglas testified that about 30% of her revenue comes from AdX— and another 10-15% comes from a Google licensing deal.

Early in her questioning, Karen Dunn put up a picture of the wikiHow website with a typical search result page for the search “How to set a thermostat.” I noticed the second result was an article on how to change the thermostat in your car. With thoughts of the hard ways of capitalism in my head, and of CEOs insisting the court must tailor its remedy to protect their assets, it crossed my mind that wikiHow is taking business away from the Joe’s Auto Shop around the corner by teaching people to change their own thermostats. And if AdX gets sold to an existing SSP, and wikiHow has to do another setup, “put work into it,” maybe the nerd teenage child of one of their 30 employees will get hired to do the setup. Every misfortune is someone else’s lucky break.

So, I came away from day eight thinking, everybody says the thing I value has to be protected, the court has to value asset prices or efficiency or small business or my state-of-the-art product people love. But it’s not true. The court can do whatever it wants in service of prying open competition.

Another fascinating day in court!