Day 11: Closing the Case on Open Source

The DOJ's last rebuttal witness explains how open-source DFP software would work; Google tries to rebut the rebuttal; Judge Brinkema has a few parting words; and the author reflects on big themes.

Day 11 was the end of the Google ad tech remedy trial, or this phase of examining witnesses, anyway. Briefs are due November 3, and closing arguments will be made in front of Judge Brinkema on November 17. The judge will hand down her opinion a few months later. The final day was very short—one witness (basically), an hour and a half total—and not much happened, though it did end with a bit of fireworks that I’ll get to. First a brief recap.

Advertising technology basically funds our digital economy, so these markets that Google dominates (illegally) determine who gets funded and how our digital world develops. The main question is whether Judge Brinkema is willing to break up Google. “Breaking up Google” is the common expression for what the court calls “structural remedies”: remedies that involve changing the structure of Google in order to eliminate its monopolies and restore competitiveness to the advertising technology markets. Google has lost three out of three trials for illegal monopolization of different markets, but avoided being broken up in the first two. In this one, the structural remedies proposed by the Department of Justice are three-fold: divest Google of its advertising exchange (AdX); make the auction logic of its ad server (DFP) open source; and divest the remainder of DFP, if the first two don’t accomplish the court’s goals.

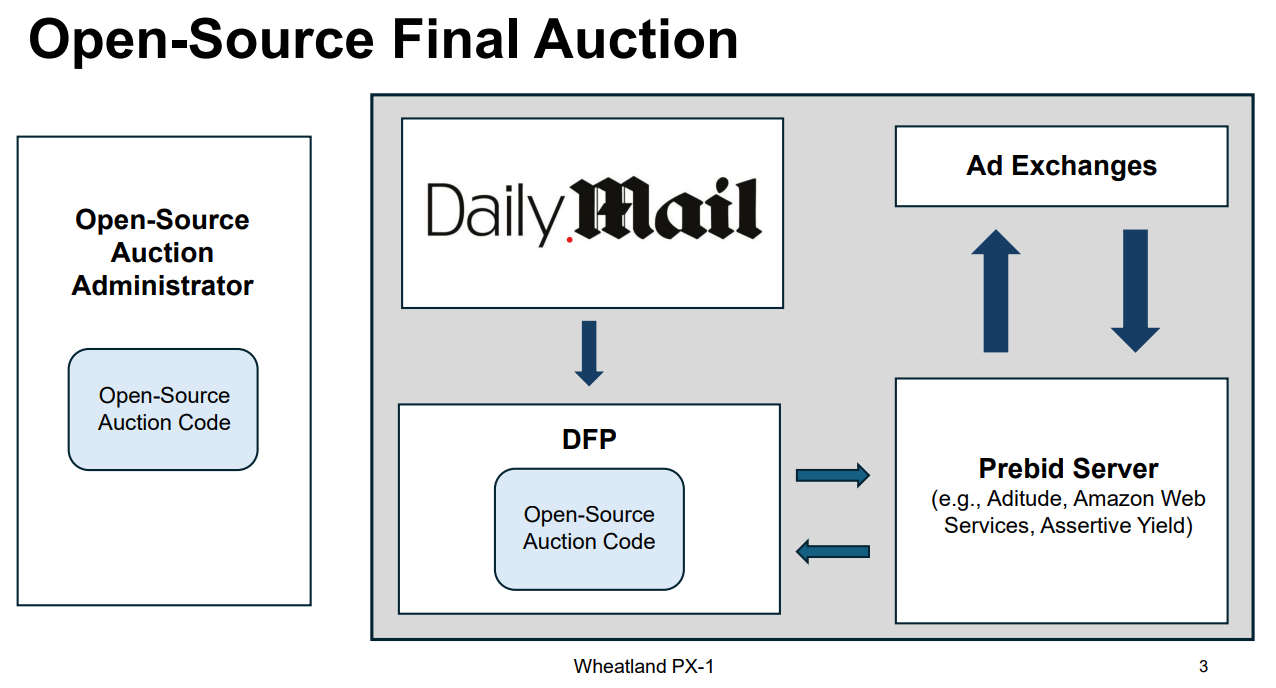

DOJ’s final rebuttal witness was Matthew Wheatland, Chief Digital Officer for the Daily Mail. Most of what Wheatland said (questioned by Julia Wood) reiterated what several other publishers have said. (A detailed blow-by-blow is here.) I thought the most interesting thing was the detail he gave about how he expected open-sourced DFP auction software to work, from the user’s (customer’s) standpoint. It was interesting not just because this led to the fireworks but also because it was the clearest statement I heard all trial of these mechanics. Wheatland said that once DFP’s decision logic was open-source, he expected it to work like Prebid’s software and DFP to work like other ad servers: a default version of the software would be pre-loaded on DFP’s server that the user could use without change; or the user could upload to DFP’s server a version from the administrator of DFP’s open-source software (Prebid or some other entity), and run that; and one or both of these would allow various features to be turned on or off by the user. He considered this to be the standard practice of other ad servers besides DFP.

The cross-examination by Jeannie Rhee focused on Wheatland’s testimony being predicated on the user being able to “upload the open-source code to DFP and run it there,” which, indeed, it plainly was predicated on. She showed some passages from DOJ’s proposed final judgment and some DOJ diagrams to argue that DOJ’s proposal was for the divested open-source DFP code to run elsewhere, in some non-DFP-server environment. Judge Brinkema asked Wheatland, “Which way would you find more beneficial?” He said that, as long as the code is truly open-source and transparent, it would be simpler, less disruptive, and less overhead if it stayed in DFP.

On redirect, Wood, too, showed passages from DOJ’s proposal to argue that the nature of the code is their concern (open-source and transparent), but the location where it will be run is unspecified; furthermore, if DFP were still functioning as an ad server, then presumably it would be running software on its own server, and that software would presumably be this open-source version of its old software.

After Wheatland was dismissed, Karen Dunn for Google requested that they be allowed to recall Jason Nieh to rebut Wheatland, because—she claimed—what Wheatland has described is different from the understanding of DOJ’s proposal that has prevailed throughout this trial. (These are the aforementioned fireworks.) Brinkema allowed Nieh back to the stand, but only for four or five questions specifically on Wheatland. Nieh then claimed that this uploading to DFP couldn’t be done, and Brinkema asked him if the decision logic in question isn’t already there in DFP. When Nieh and Rhee start into Jon Weissman’s and Goranka Bjedov’s technical testimony, Brinkema cut testimony off there as beyond the scope of rebuttal. Wood, on cross, tried to ask about the Google internal feasibility studies, and Brinkema cut her off, too. The end.

There was a post-witness epilogue of court business: the reading into the record of the list of exhibits and other such things. The last words Judge Brinkema left us with are a reminder that her favorite phrase is, “Let’s settle this case.” I don’t think anyone expects the two sides to accommodate her on that one.

There is something very odd about Google’s last-minute claim that DOJ has slyly changed their proposal for open-sourcing DFP’s final decision logic. Here is the oddness: DOJ’s Matthew Huppert cross-examined Glenn Berntson on exactly this point at considerable length on day seven. Their issue was whether the code would be executed outside DFP while the data on which the code operates was inside DFP, causing horrendous data transmission demands, according to Berntson. Huppert repeatedly asked him if running the open-source code inside DFP would solve that data problem. You may recall that I discussed their discussion at considerable length in my day seven post. And if a head-in-the-clouds philosopher can see that this is a fundamental point on which the two sides have incompatible interpretations of what open-sourcing DFP means, surely the lawyers knew it, too. One might casually think, oh, the silly lawyers got confused or were distracted on day seven, but I don’t buy it. This is Google we’re talking about and, as the saying goes, Google has more money than God. These are, therefore, the best lawyers that money can buy. I don’t think they’re confused, or just weren’t listening when Huppert cross-examined Berntson. My only guess is that this claim that DOJ illicitly changed the meaning of divesting the Final Auction Logic that had prevailed “throughout this trial” is Google’s lawyers laying groundwork for a future appeal.

Judge Brinkema praised both sides for a very well run trial. And the lawyers on both sides were impressive. I believe there is a further subtext to this “both sides” idea, though, a subtext vital to DOJ’s case: not only the lawyers but also the witnesses for both sides were impressive; and, by extension, Google’s engineers and the engineers of its competitors are also equally impressive. The implication is that talent is very widely dispersed and relatively equal, and any number of other people and companies could accomplish what Google has accomplished.

To counter this democratic picture, Google drew on other themes familiar in our society, especially in science fiction. The sci-fi trope of “the one” was always present, the one person or entity with special powers possessed by no other, special abilities needed to meet the moment; we need what only Google can give. A similar sci-fi trope surrounded Google’s source code, which was relentlessly portrayed as complex beyond comprehension, like some superior technology left us by an ancient civilization. We poor humans can run and benefit from this machine, but cannot understand or change it, let alone divest such a mysterious and untouchable and incalculably precious gift into the sacrilegious hands of tinkerers.

These tacit ideas that Google drew on in its defense are the concepts that support oligarchy, and they have been growing in our society far beyond science fiction and fantasy literature. The titans of finance and industry are commonly presented in similar terms as possessing special genius. Their biographies and their pay packages are of absorbing popular interest. Consequently, the decision in this antitrust case, though redressing arcane markets and technologies, will resonate widely due to these tacit themes it expresses.

DOJ was right to take these themes on directly. The opponents of Google that DOJ presented were not the small customers suffering extraction of Google’s monopoly rents. They were highly capable competitors, some of them CEOs and officers of hundred-million-dollar companies being stifled by Google’s control of both data and markets. The heart of this case was not a moral plea for fair treatment of the little people by the mighty. It was an epistemological claim about the vital role of competition in the on-going development of technology, competition among people of hugely diverse circumstances and specific knowledge yet relatively equal abilities.

Most observers still consider this case a toss-up as to whether Judge Brinkema will force divestitures on Google. Put me in the lean-DOJ camp. I lean divestiture partly because it is hard to imagine how making Google behave better could possibly eliminate its monopolies when it has a 91 percent share of the ad server market. And Andres Lerner’s weird efficiency claims notwithstanding, eliminating illegal monopolies remains the clear and primary purpose of antitrust law.

But I lean divestiture also partly because DOJ made its technical feasibility case not by arguing technical minutiae but by arguing that Google’s engineers follow industry best practices: they write modular code that is well documented, readily updated, and flexibly moveable. That is, Google may have the best engineers that money can buy, but they are still engineers, not a priesthood guarding a sacred technology. Google’s engineers put their pants on one leg at a time, just like the engineers of their competitors. A victory for the government in this ad tech remedy phase would be a victory for that home-spun, democratic truth.

In any event, we’ll see how the parties frame their final themes at closing arguments just over a month from now, on November 17th.

Brilliant closing analysis!